If you wish to make an inventory of my sex life, dear, I think it’s only fair to tell you that you've missed out several episodes. I shall consult my diary and give you a complete list after lunch.

Blithe Spirit (1945) is, of course, today rightly considered a classic. Yet, surprisingly, opinion at the time was divided. Noel Coward hated it. "My dear, you've just fucked up the best thing I ever wrote…" he said to David Lean on first viewing, wringing his hands, especially over David Lean's 'static' direction (which failed to hide the stage origins), and the ending, which Lean changed for the film, and wasn't in the original play.

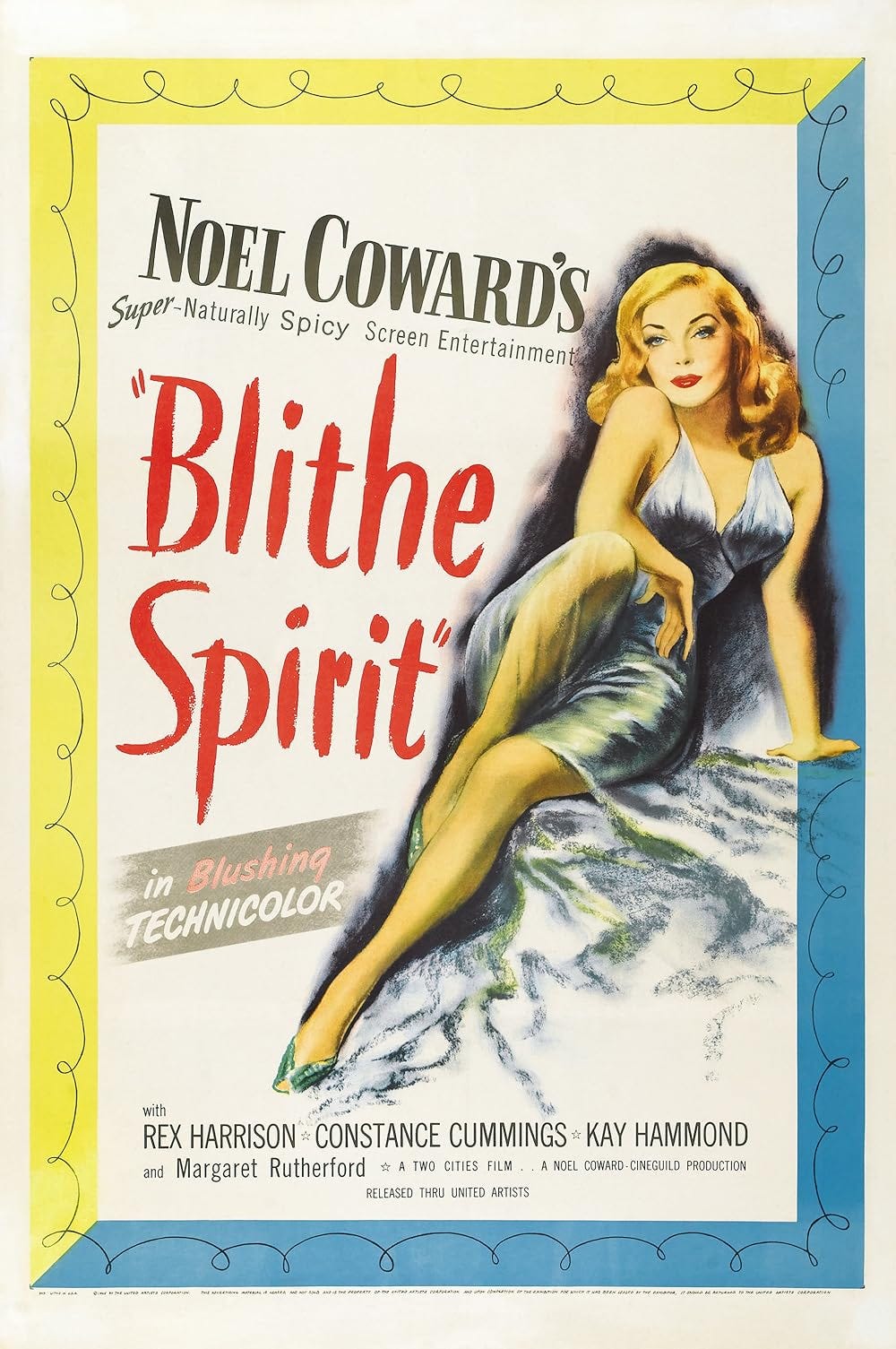

Producer Anthony Havelock-Allan (aka Mr. Valerie Hobson, later Profumo), with hindsight, regretted the casting: Rex Harrison was too young (he was 37) and, in his opinion (and the crew's), Constance Cummings (the second wife) was sexier than Kay Hammond (the ghost), which kinda defeated the whole raison d'etre: Charles Condomine is a well-heeled, ageing thriller writer, settled in a stable, if sensible, second marriage with brisk, smart (in the English sense of fashionable) wife no. 2 (Ruth), suddenly re-awakened and rejuvenated by the ghost of flighty, sexy, exciting wife no. 1 (Elvira). And as much as I like Kay Hammond (she's marvellously blasé), I see where Havelock-Allan's coming from. The original film poster (below) portrays Elvira as a seductive 40s vamp. She looks entirely different from Kay Hammond.

I expect you know the plot, but even if you do, let's have a recap: Charles (Rex Harrison) is a successful thriller writer, married for a second time (his first wife died seven years before) to the efficient Ruth (Constance Cummings). In the interests of research (Charles's latest novel has, presumably, an occult theme à la Dennis Wheatley), the couple invite the local medium, Madame Arcati (Margaret Rutherford), to dinner alongside the unimaginative local doctor (Hugh Wakefield) and his unimaginative local wife (Joyce Carey). And the Condomines live in a splendid Regency villa, a cottage orné with a verandah, the sort of thing you might find in Sussex or on the Kent coast, but actually filmed at Denham Mount, a house (unsurprisingly) found near Denham Studios, Buckinghamshire— near the charming and quaint village situated on the outskirts of London, close to the old Middlesex border. These days, Denham village is an olde-world oasis of re-pointed red brick, popular with television and film people (famously Sir John Mills, Roger Moore and that bloke on Tomorrow's World), and surrounded on one side by the dual carriageway of the A40, the M25 on the other, a spaghetti junction of roundabouts, scrappy allotments, market gardens, sinister canals and concrete flyovers.

Although Blithe Spirit was filmed in May 1944, in the month before D-Day, it's as if the war didn't exist. It's extraordinary. The characters live a luxurious, post-war (late 1940s) or pre-war (late 1930s) Technicolor fantasy. No blackout curtains for them! Lights blaze away in an immaculate, fully staffed house— a juicy, if random, target for a stray V1 or V2 rocket. Petrol seems to be in abundant supply: no petrol rationing for the dashing white 1938 Triumph Roadster, or blackout strips for the headlights. Food's plentiful: there's a juicy cut of beef (pink inside), black coffee, and a well-stocked drinks tray for the (brown?) Martinis, at a time when gin, as with whisky, was incredibly scarce. The girls are beautifully dressed.

And as with so many other films with a theatrical background, the house is as much the star. It's a delicious slice of late 1940s upper-middle-class English life, a blueprint for understated Anglo-American civilisation: the dark blue chintz curtains, the globe in the library, the serried ranks of hardback thrillers (with dust-jackets), the 'Chippendale' mahogany, the longcase clock and sub-Impressionist painting in an Impressionist frame, the rather grand American staircase (do English houses ever have these?), the drinks table, the comfortable sofas and luxurious double bed, the gold coffee cans and the splendid Syphon coffee percolator with the little spirit lamp. All this is very similar to Dennis Wheatley's set-up— at Grove Place, his Georgian house in Lymington (now, alas, demolished). And the characters speak proper, like. How refreshing. Yet, at the same time, all this is rather modern— as the late 1940s can be— you could easily wear Rex's double-breasted dinner jacket and soft-collared evening shirt today, and the house— give or take a tweak and a television set— might grace the pages of House & Garden.

For although Blithe Spirit turns a blind eye to the war, the subject matter— when you think about it— is pretty sharp. I mean, the play's a black comedy about not only sex but— wait for it— death. And death, of course, was very much with us in 1945. Coward's genius was to handle a tricky theme with brittle indifference, which gives the film an edge— a quality picked up by the perceptive Harold Pinter, an early champion of the Coward revival. At the same time, perceptive David Lean realised that the British public craved civilian escapism and colour (as opposed to earnest war films in black and white): the saturated Technicolor of Blithe Spirit was also an attempt to break into the American market. And the British public loved Blithe Spirit, partly, I think, because the idea of a loved one returning, albeit as a ghost, appealed— for obvious reasons.

But, beneath the dry humour, it's very much a film about the failure of marriage. And sexual jealousy. As with the Girl in Daphne du Maurier's Rebecca (1938), second wife Ruth is bitterly jealous of late-departed wife numero uno: a bitchy catfight in ectoplasm. As they say, 'hell hath no fury like a woman scorned':

Charles: I haven’t forgotten Elvira… I remember her very distinctly, indeed… I remember her physical attractiveness, which was tremendous, and her spiritual integrity which was nil.

Ruth: Was she more physically attractive than I am?

Charles: That's a very tiresome question, darling. It fully deserves a wrong answer.

And thinking about it, Elvira's demise comes about as a result of deceit. Galavanting on the moors with the dashing Captain Bracegirdle leads to pneumonia and, ultimately, her death (although she has a heart attack from laughing)— upstairs, in one of the bedrooms. How creepy is that? And this idea of a haunted first wife. Where does it come from? A fashionable theme in the late 1930s? Jane Eyre? But I see this time and time again. How specific themes and ideas seem to crop up simultaneously, often within a few years of each other. Something in the water supply?

So there you go. Blithe Spirit (1945). Perhaps there’s more to it than at first meets the eye. In any event, casting aside, it’s a terrific film— and up there in my All Time Top Twenty Film List. And there’s nothing I would like more in the world than Blithe Spirit and an accompanying Dry Martini. Somehow that cocktail seems appropriate. I watched Blithe Spirit (1945) on DVD, and I need to upgrade to the digitally restored and remastered edition. Thanks to the Technicolor, it’s a visual treat. It is, of course, also available to download on Amazon Prime Video for a handful of golden nuggets.

You’ve just been reading a newsletter for both free and 'paid-for' subscribers. I hope you enjoyed it. Thank you to all those of you who have signed up so far.

There are two options on Luke Honey’s WEEKEND FLICKS. Cinema for Grown Ups: ‘Paid-for’ subscribers get an extra exclusive film recommendation every Friday morning, plus full access to the complete archive— which is currently at film no. 82, and should list over a hundred films by the end of the year. It costs £5 a month (or £50 a year)— a bargain, frankly, when you compare it to a few cups of coffee, a packet of semi-legal gaspers, or a pint of beer in the pub. ‘Free’ subscribers get access to the Sunday newsletter, plus the ‘free subscriber’ films in the archive. Either option is a good bet. And when I get my act together, I’m planning to add a spoken voiceover (mine!) for paid subscribers.

I will be back next Friday. In the meantime, I hope you have a relaxing and cinematic Sunday.

Wonder if that film would be made today?

Superficially glossy and light-filled, but in fact a dark and emotionally murky film. Its great distinction is that it is possibly one of the few films of any era, let alone the deeply repressed forties, where three people get to live together happily, or otherwise, ever after.

(PS I agree entirely with Coward re the film versus the play ending).