Twiglets, Beethoven and Class Warfare: Abigail’s Party Revisited.

Welcome back to WEEKEND FLICKS. Cinema for Grown Ups: film that still resonates. This Sunday: Abigail’s Party (1977) — a brilliant and brutal take on aspiration, taste, and emotional entropy in the London suburbs.

It’s time for a lemon slice of television history. Time for Abigail’s Party, Mike Leigh’s bleak, sharp-as-a-razor comedy of English lower-middle-class manners, set in the outer suburbs of London and first broadcast as a BBC Play for Today on a rainy Tuesday night in November 1977. The premise is this: Abigail, Sue’s teenage daughter, throws a party, forcing her mother to spend the evening with her neighbours, Laurence and Beverly (a childless couple) and their guests, first-time house buyers, Tony and Angela. Time for a gin and tonic. Time for Twiglets and Pineapple Squares on a Cocktail Stick (‘Nice and Dainty’). Time for Demis Roussos and a Bacardi and Coke.

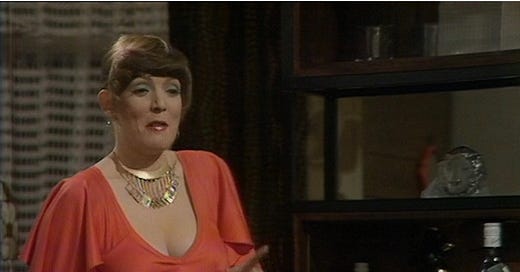

Laurence (Tim Stern) is a stressed out, albeit successful estate agent, going places — while his wife, brassy Bev (played memorably by Alison Steadman), is a former makeup girl, one of those hard-sell ‘beauticians’ positioned, strategically, in the ground floor foyer of a famous London department store, Harrods, Selfridges or Harvey Nicks. And then there’s monosyllabic Tone (John Salthouse), a bearded Neanderthal (man-made fibres), potentially violent, who ‘once played for Crystal Palace’— and his dreary, tactless, annoying wife, Ange (Janine Duvitski) who’s a nurse: kind, bland, and entirely lacking in irony, but great in a crisis. A group which have escaped their working-class backgrounds to form a new, aspirational lower-middle class: the sort of people who tell you about the value of their property and how much money they have made when you have only just met and they know nothing about you.

Genteel Sue, ‘from No. 9’ (Harriet Reynolds) is the odd one out. Poor, wet, downtrodden, divorced architect’s wife, Sue, (“your husband’s run off with another woman”) who brings a bottle of Beaujolais expecting food, and half an hour in, pukes in the loo as she’s not used to drinking on an empty stomach, and she’s thinking, “What on earth am I doing here? These ghastly people” — but is too well brought up to do or say anything about it.

For unlike the others, sensible Sue is from the educated middle-middle class. She lives, presumably, in one of the larger, older Edwardian houses in the street, an exercise in Mock Tudor, William Morris wallpaper and a dusty ‘Sun Room’, a garden of sodden rhododendron bushes surrounded by new-build estates sprouting like tarmacked mushrooms. Laurence asks Sue if she regrets the ‘change in the neighbourhood’ (i.e. immigration) when Sue — I suspect — is privately thinking that it’s people like him who have lowered the tone. Oh, the irony! Poor Laurence, of course, is working his socks off to keep the spoilt and ungrateful Beverly in the style to which she was unaccustomed before she met him. Laurence is clearly good at his job, and there’s no problem with the cash flow. There’s an executive leather sofa (sorry, ‘suite’), a well-stocked bar, Habitat dining chairs and a sort of Tiffany lamp knock-off. And there’s a chic little terrace with trendy Victorian garden furniture in cast-iron white. Jet set aspiration. Sue, surely, is far more frugal, and her house less glitzy (at least, in my imagination): brown furniture, a threadbare fitted carpet (pea-green) and cedar-wood panelling in the hall, like the inside of a cigar box. Hardback fiction (John Fowles and Beryl Bainbridge) with dust-jackets. The central heating turned down. Ticking clocks. No vulgar cocktail trolley, limited edition Lowrys or expensive Hi-Fidelity systems in her house. She shops at Sainsbury’s and on the wireless, there’s Radio 4 and the Shipping Forecast. An early night in and a cut-glass of sherry.

Despite the economic gloom, the 1970s was a time of aspiration and consumerism, fuelled, I think, by the credit card, first brought to Britain in 1966. We’ve been living off credit ever since. Which explains, today, the sheer number of bloated, ostentatious, so-called SUVs on Britain’s roads. The things with Four Wheel Drive. Often seen parked outside modest dwellings on flat, busy roads. They’re bought on the drip: an essential requirement for the muddy, treacherous, cherry-lined avenues of the London suburbs. And hand in hand with the credit card, came the Sunday Colour Supplement, which juxtaposed the new luxury — advertisements for cognac, aftershave, Viyella, expensive cigarettes and Martini Rosso — set against harrowing, grainy photo-journalism of atrocities in Vietnam or child poverty in the East End. It meant, for the first time, that people could live beyond their means. Before the credit card, there was the bank loan: which meant a scary interview with a patronising, nosy and interfering Captain Mainwaring at your local Barclays Bank. By appointment only.

And that’s another interesting thing about Abigail’s Party (1977). It’s set amongst a class who, actually, were “doing rather well, thank you very much” — yet, in a decade now fashionably depicted as a time of strikes, three-day weeks, incompetent government and rat-infested rubbish piled high in Leicester Square. Laurence and Beverly are like burgeoning proto-yuppies, a cultural premonition, yet two years before the Thatcher revolution, a sign of what was to come: Porsches (Kermit Green), Red Braces, Big Hair, The Right to Buy and the Big Bang (the deregulation of the City of London); Loads of Money. Interestingly, I think, significant economic signals can sometimes occur before the event, weirdly anticipating future happenings: see how the London stock market began to recover in October 1940, following the Battle of Britain, when many political commentators were still predicting this country’s demise. The disconnect between economic indicators and public and political sentiment is notable. Mrs Thatcher and the Sex Pistols, the New Guard (anti-establishment radicals, both), have far more in common than they probably care to admit. For something was in the water in 1977. It’s remarkably prescient.

Alison Steadman’s Beverly is, of course, a monster: deeply selfish, and fundamentally unhappy, with her constant, ghastly repetition of her guest’s first names, “Ice and a slice of lemon, Sue?”, her St Moritz super-length cigarettes (so jet set!) and her undermining passive aggression. “Do you like Menthol, Ange?” she says — actually, I’ve made that up, but it’s the sort of thing she might have said.

I’ve seen Abigail’s Party (1977), half a dozen times over the years — and watched it again last night. The problem I have is that it can come across as more than a trifle sneery. You know, the lefty Hampstead intellectual crowd (indeed, before the television adaptation, the play was first performed at the Hampstead Theatre in Swiss Cottage), with their rancid cats, stacked newspapers and the rambling, red-brick of gloomy Victorian houses off Fitzroy Avenue, laughing at the crassness of the gauche, unsophisticated, uneducated and pushy lower-middle-class. As Dennis Potter said in The Sunday Times:

(Abigail’s Party) is "based on nothing more edifying than rancid disdain, for it is a prolonged jeer, twitching with genuine hatred, about the dreadful suburban tastes of the dreadful lower middle classes.”

An accusation which Mike Leigh denied, and watching it again, I’m still on the fence. Leigh, perhaps, is making a statement which might be interpreted in either direction: an exploration of the futility of British life (when actually, Seventies Britain was a relatively happy place); for there are no redeeming qualities. There’s an element of hate, the characters clearly loathe each other: it’s brilliant, toxic and pretty depressing. And thinking about it, there’s a superficiality not unlike the American Dream of Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman (1949).

But if, in Death of a Salesman, there’s an empathy for salesman Willy, Abigail’s Party is more ambiguous. Are we supposed to laugh with or at the characters? Are we not seeing them through the eyes of educated, middle-middle class Sue? I mean, I rather like Laurence, or at least, admire his intense aspiration — his frustration with the philistine Beverly, his frantic desire to embrace the finer things in life — like a desperate culture vulture: the proud owner of a Heron Shakespeare set in ‘real leather’ with ‘embossed gold’ (“our nation’s culture, not something you can read of course”); his Van Gogh and L. S. Lowry reproductions, his Deutsche Grammophon recording of Beethoven’s Fifth, which provides the backdrop to the play’s final denouement. Laurence is very much a candidate for the Reader’s Digest, for Kenneth Clark’s Civilisation (1969), for the coffee table book of the BBC series, Royal Heritage (1977) — broadcast that year — even if, perhaps, one is supposed to nod sagely at his shallowness and lack of understanding and despise his political values. For in the 1970s, unlike today, the punters aspired to the trappings of Old Money, as pedalled by the glossy ads in The Sunday Times and Observer colour supplements, Lord Lichfield and Lady Annunziata Asquith flogging Burberry, Daimlers parked outside Blenheim Palace, a Napoleonic wargame and a balloon glass of brandy — the leather-lined library of an ancient French chateau given a suburban twist: the faux Morocco of sinful Kidron.

I watched Abigail’s Party (1977) via Amazon Prime Video digital download. It’s also available on DVD and Blu-ray. I’m not sure if the entire thing can be seen on YouTube. I hope it is, but so far I’ve only found snippets — but with further research you might be able to dig something up.

You’ve just been reading a Sunday morning post for free subscribers. Thank you for that. But may I dangle the ‘paid subscription’ option in front of you, like a juicy carrot? It costs a mere £5 a month or £50 a year. That’s the price of a few cappuccinos or a half pint of ale. If you liked this piece, please hit the ♡ button, share it, or consider becoming a paid subscriber. Friday morning bonus posts are for members, and the archive is yours to explore — 142 films and counting.

A classic snapshot of social gymnastics and the ridiculousness of the trappings of class playing out in a truly awful brown and mustard living room! I loved this play, in fact I rewatched it just before Christmas and enjoyed. Fantastic review as always Luke!

Very astute commentary. I think it's stood the test of time extremely badly. One ends up despising the impetus of Leigh in writing it rather than the characters themselves. And your observation that in the Seventies, the aim was the acquisition of the trappings if Old Money was spot on.