I’ve thought for some time now, that if, by some occult osmosis, one could travel back in time and space, then a Woody Allen movie — from the late 1970s — might be a very good place in which to land: a tweedy, autumnal, golden Manhattan. The clothes of Brooks Brothers, J. Press and early Ralph Lauren — in the days before the hideous, vulgar, oversized Polo logo — a Manhattan of old-school diners, Yellow Checker taxis, art-house cinemas, wafer-thin office girls in Fürstenberg wrap-around dresses, transparent glasses; neat, compact modern apartments with framed art exhibition posters, uniformed doormen, discount bookshops, VW Beetle convertibles, steps leading up to those Victorian brownstones, (brown being the operative word), Palmists’ hands in neon, and the curious pink light of Long Island Sound, which accentuates the yellows and reds, of taxis, traffic lights and fire hydrants; Andy Warhol, Disco Sally and Studio 54. With hindsight, these things seem rather appealing. They have that undefinable certain something. For Woody Allen’s New York ain’t the New York of Kojak (1973-1978), Saturday Night Fever (1977), Taxi Driver (1976) or The Warriors (1979). As Martin Scorsese said in Woody Allen: A Documentary (2011), “Woody's sensibilities of New York City is one of the reasons why I love his work, but they are extremely foreign to me. It's not another world; it's another planet.”

And as with London, New York is a photogenic town. Here, on this side of the Atlantic, I lament a London Lost — for the rapid pace of change has removed endless favourite haunts or would-be haunts: restaurants, shops, galleries and museums, many of which had been there for a very long time indeed. I could make up a list of beloved London institutions. Every single flippin’ one has gone: Odin’s, Jules’ Bar, the original Annabel’s, The India Club, Jack’s Place (Battersea), San Frediano in South Ken and Green’s restaurant in St James’s; Pollock’s Toy Museum, Maitland Chemist, Bate’s the Hatter, Sullivan Powell Tobacconists, Jackson’s of Piccadilly, Pucci Pizza, Under Two Flags (a charming toy soldier shop in St Christopher’s Place), Fenwicks in Bond Street, The Fine Art Society (now removed from its historic Bond Street premises to Holborn), The Red Lion just off Curzon Street, a country pub in the heart of Mayfair. All defunct. These You Have Loved. With two cherished South Kensington institutions, Daquise (the famed Polish restaurant, founded 1947) and The Medici Gallery (founded 1908) set to bite the dust. All swept away by the cost of increased rents. Covid didn’t help either. And to be frank, I struggle to reassure you that their replacements are an improvement. Take Bate’s, the eccentric hatter of Jermyn Street, which boasted one of the last intact shop interiors of the 1920s: demolished to make way for yet another bland, upmarket underwear chain à la Heathrow Airport. New & Lingwood (the original deal, founded 1865) has undergone transformation (some design wunderkind?) and is now decorated with ersatz props: a tartan carpet and ‘vintage’ paintings which look like they’ve come off the railings on the Bayswater Road. The Curzon cinema, a lovely example of stylish 50s modernism (more than a whiff of the Côte d’Azur) and home of the sub-title, is also threatened with demolition.

It’s the same, alas, with Old New York. A Tale of Two Cities. In 2021, Time Out magazine listed ‘30 iconic (their word) NYC institutions that have permanently closed’. These include the Peoples Improv Theater, Jing Fong, Gem Spa, Barneys, Neiman Marcus (founded 1907), the 21 Club (I’m especially sore about that one), Chumley’s, China Chalet, Coogan’s, Gotham Bar and Grill, Scribner’s and the Strand Bookstore, John Jovino Gun Shop (founded 1911), the Roosevelt Hotel, Max Fish and Lord & Taylor. I might also add to the list Elaine’s restaurant, featured in Woody Allen’s Manhattan (1979), which closed in 2011. Miraculously, P. J. Clarke’s on Third Avenue (The Last Days of Disco) is still with us.

Working for Phillips Auctioneers in Yorkville, at the far end of the Upper East Side, I moved into The Olcott Hotel — an eccentric, shabby set of rooms on the Upper West Side, ‘once home to a posh New York crowd’ and bang next to the Dakota, which meant a pleasant walk to work through Central Park. Joseph Berger, writing in The New York Times on April 25, 1992, said, “It is not really a hotel you can check into for the night. Many of its 240 residents checked in 30 years ago and never repacked their suitcases. It is a residential hotel, an apartment house mostly for lazy people who do not want to make beds, cook dinner or buy furniture.” Here, Mark Chapman holed up before shooting John Lennon, a location which appears in Rosemary’s Baby (1968), The Stepford Wives (1975) and Taxi Driver (1976). There was a creaky lift (presumably 1920s?) Like something from a gangster film. And now The Olcott is another one we can add to the list: following redevelopment, it is now a squeaky-clean, luxury Condominium.

And as time passes, nostalgia — the snapshot of New York as it then was — adds an extra dimension, a feel-good charm to the Woody Allen films of the late 1970s and 80s. But then Woody’s films have an in-built, wistful nostalgia before they’ve even begun. I’ve been writing WEEKEND FLICKS. Cinema for Grown Ups for just over a year now, and scrolling back through the archive, for some unfathomable reason, I have failed to include a Woody Allen film on our list. So far. This needs to be corrected. For as you have probably gathered, I am a huge fan. Woody Allen is an original — and in my opinion, one of America’s greatest film-makers. But if you’re new to Allen’s films, where do you start? Woody Allen is or was a prolific filmmaker — he liked to make a film a year— which creates a challenge for Woody Allen completists. But from the top of my head, my favourites (so far) are: Annie Hall (1977), Manhattan (1979), Play it Again Sam (1971), Stardust Memories (1980), Hannah and Her Sisters (1986), Crimes and Misdemeanours (1989), Husband and Wives (1992), Manhattan Murder Mystery (1993); the delightful musical, Everybody Says I Love You (1996), Small Time Crooks (2000), Melinda and Melinda (2004) and Match Point (2005).

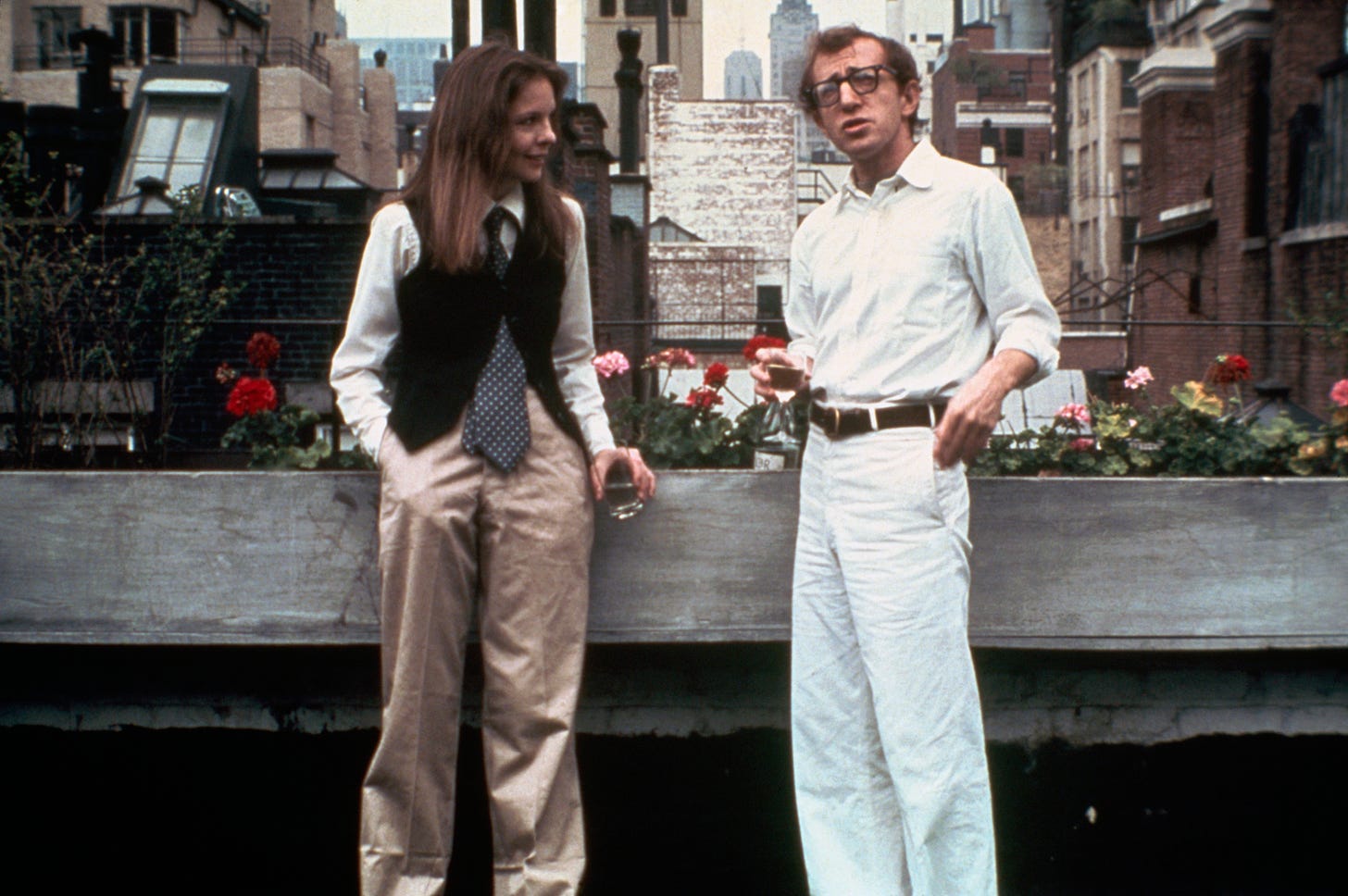

The cinematic world seems to be split down the middle. You’re either a fully-paid up Woody fan — or you just don’t get it. I suppose the dry humour is an acquired taste, the sophisticated, witty banter, the amusing intellectual and cultural references, the self-deprecating Jewish neurosis and constant self-analysis, the influence of Ingmar Bergman. But Woody’s films, perhaps, are enjoyed even more as you advance in age. My first Woody Allen, was Manhattan (1979), starring Mariel Hemingway and Meryl Streep (‘my wife left me for another woman’), screened at our local cinema (I was a tender fourteen) and, of course, it went straight over my head. These days (I’m slightly older), I can watch a Woody Allen film over and over again, and every time discover a little bit more. For his films are about the human condition, the ups and downs of real life, and relationships. Which takes us to Annie Hall (1977), a comedy of manners, and quite possibly one of Woody Allen’s greatest films — and, if you’re new to Allen’s work, a very good place to begin.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Luke Honey's WEEKEND FLICKS. to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.