The first half of the 1980s was a Golden Age for British cinema. The Long Good Friday (1980), The Elephant Man (1980), Chariots of Fire (1981), Gregory’s Girl (1981), The French Lieutenant’s Woman (1981), An American Werewolf in London (1981), Moonlighting (1982), The Draughtsman’s Contract (1982), The Return of The Soldier (1982), Local Hero (1983), The Hunger (1983), Educating Rita (1983), Dreamchild (1985), A Company of Wolves (1984), A Room with a View (1985) and Dance with a Stranger (1985): all of these films I rate highly: visual, aesthetic and beautifully written, sometimes both.

I’m trying to get my head around the 1980s- that puzzling, head-scratching, contradictory decade. Thinking about it, there’s no logical reason why the 1980s should start in 1980, apart from a tendency for historians to tidy things away in boxes. It may have started in 1977, alongside zipped tartan trousers, pierced ears and safety pins. In Britain, I see two opposing energies. Mrs Thatcher’s so-called traditional ‘Victorian Values’. And against that, a spiky, edgy, radical force- like a seismic plate, rubbing up against a new-found vitality. Yet, simultaneously, the two things are very much part of the same- like the Yin and the Yang. Vivienne Westwood and Colefax & Fowler may have more in common than they imagine.

The Anthony Blunt scandal of 1979 captured the zeitgeist. When Sir Anthony Blunt, KCVO- distinguished art historian, ex-Marlborough and Trinity College, Cambridge and Surveyor of The Queen’s Pictures- was exposed as a Soviet spy. This idea, this concept, of an establishment riddled with corruption and subversion- a maggot at the heart of government, is a theme which crops up time and time again in television and films of the period- the pin-striped, plummy Old Harrovian minster as Soviet double agent- almost a cliché, as seen in episodes of The Professionals (1977-1983) and the patriotic SAS adventure flick, Who Dares Wins (1982), starring Lewis Collins and a Neanderthal MP5- a theme, which significantly, I think, coincides with the Big Bang of 1983. When, overnight, Mrs Thatcher destroyed the ways of the traditional City of London- top hats replaced by red braces, Porsches and ‘Loads of Money’.

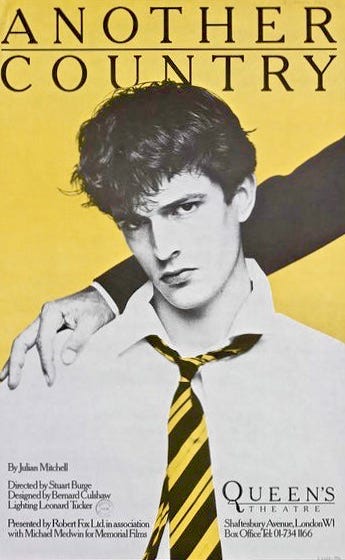

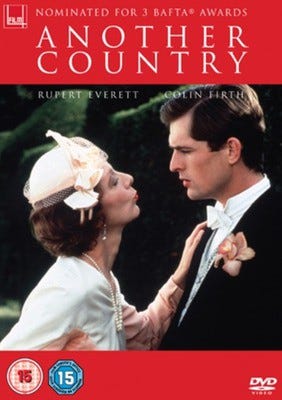

Which takes us to Another Country (1984). Julian Mitchell’s screenplay is based on his original play (first performed at the Greenwich Theatre in 1981), establishing Rupert Everett and Colin Firth as major talents. Goldcrest, the production company most associated with the British film revival of the early 80s (also responsible for Chariots of Fire, Local Hero and A Room with a View) then financed the film version, directed by Marek Kanievska.

Bennett (Rupert Everett) and Tommy Judd (Colin Firth) attend an unnamed British public school in the 1930s, possibly Eton. Bennett and Judd are outsiders. Bennett (clearly based on Soviet double agent Guy Burgess) is homosexual; Judd (based on the poet, John Conford, Esmond Romilly or similar) is a committed Marxist. Yet there’s a significant difference. Judd’s an anti-establishment Communist Revolutionary. Bennett, on the other hand, yearns to be recognised, to reach the dizzy heights of the ‘Gods’, (‘The Twenty-Two’), an elite sub-strata set above the prefects, a self-elected oligarchy based on Eton’s ‘Pop’, entitled to wear a brocade waistcoat and ‘stick-ups’ (wing collars). It’s this rejection- a hypocritical reaction to his open (as opposed to hidden) homosexuality- which turns Bennett to Communism- to betray his country. After all, it’s not what you do that counts; it’s how you do it.

In Alan Bennett’s An Englishman Abroad (1983), directed by John Schlesinger and based on a true story, the magnificent Coral Browne meets a homesick Guy Burgess in a chance encounter, now holed up in a grace-and-favour flat in Moscow: a dodgy Russian boyfriend lurking in the shadows (like Kurt, the ex-Legionnaire in Brideshead), pining for Old School Tie and Sulka pyjamas. Another Country’s haunting opening sequence comes in on a similar tack: a Russian Zil gliding through the drab streets of Moscow, with pretty American journalist played by Betsy Brantley (Liz Hurley eyebrows) interviewing a doddery Guy Bennett (dodgy make-up); all cricket, Harrods tea bags and Bath Olivers- set to Michael Storey’s elegiac, echoing 80s electronica. Musically, we’re in similar territory to Richard Hartley’s soundtrack for Dance with a Stranger (1985), directed by Mike Newall (Four Weddings and a Funeral), also starring Rupert Everett.

Another Country joins a list of books and films in a literary and cinematic English public school tradition. A closed society where the older boys wield considerable power over the ‘fags’- the younger boys acting as their elders’ personal servants. Alec Waugh’s sensational novel, The Loom of Youth (1917), based on his personal experience at Sherborne, scandalised British society. The muscular Christianity of Tom Brown’s Schooldays (1940 and 1951) followed, the latter filmed at Rugby; the touching sob-fest, Goodbye Mr Chips (1939), filmed at Repton, and the Boulting Brothers’ stiff-upper-lip weepy, The Guinea Pig (1948), filmed at Sherborne. A working-class scholarship boy, played by Richard Attenborough, survives snobbery and physical hardship, and, like Tom Brown, ultimately triumphs. In contrast, the tail-coated revolutionaries of Lindsay Anderson’s surrealist satire, If…. (1968) gun down the establishment in the neo-Gothic environs of Cheltenham’s Quad.

For Another Country’s location, the producers approached Eton, a request which, quite understandably following the furore surrounding If…., turned down- so the film was shot, less convincingly, against an Oxford backdrop- with further scenes filmed at Dashwood’s lake at West Wycombe Park in Buckinghamshire and Smithfield’s St. Bartholomew-the-Great standing in for the school’s chapel. The title- Another Country- references a line in the patriotic weepy, set to Gustav Holst’s Thaxted. But then it might equally apply to L. P. Hartley’s The Go-Between (1953), ‘The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there’, seemingly referred to in Another Country: ‘You’ve no idea what life in England, in the 1930s, was like, treason and loyalty, they’re all relative’.

As with If…. the intense claustrophobia of the public school, town vs gown, the public school as a microcosm of British Society, is beautifully portrayed in Another Country; the earnest, God-awful prefects (aged beyond their years) like premature colonial administrators, soldiers, politicians and captains of industry. Pompous and hypocritical. And there are further direct references- almost scene-on-scene (perhaps deliberate, perhaps coincidental) to If…., the bath scene, fags cooking baked beans on a rusty stove, and the prefect beating, which despite everything, lacks the brutality and viciousness of the equivalent sequence in If…..

But I have one major quibble. At the wedding reception, at the Lutyens house, the entire (male) wedding party wear wing collar and white bow ties- worn for evening dress, rather than the usual wedding tie. My understanding (and I have inside information) is this. There was a mix up, the wrong costumes were delivered- and the director went ahead with the filming. But it does matter. Guy turns up to the wedding in the school uniform of the Gods- stick-ups, white bow tie and brocade waistcoat- to which, of course, he is not entitled- and the dramatic contrast with the other male guests is entirely lost.

Still, the attention to detail in Another Country is otherwise more or less spot on, especially the acting, a remarkable masterclass in subtlety from both Rupert Everett and Colin Firth. The lunch in the dining room of a provincial hotel (white linen and starchy head waiter) is priceless, reminiscent of a similar scene in Brideshead, with Everett’s Guy Bennett and Nickolas Grace’s Anthony Blanche playing sophisticated foils to crush, Cary Elwes, and Jeremy Irons’ impressionable Charles Ryder. It’s wry and beautifully observed. I watched Another Country again, a few days ago- a film I’ve seen many times- and I was suddenly struck by a surprising edginess- found beneath that historical charm- enhanced, musically, by the 80s electronica. Rupert’s look is New Romantic, all eyeliner, quiffs and draped cricket jerseys. The Pet Shop Boy meets Stephen Tennant, or a young, gawky Cecil Beaton. And in 1985, The Style Council referenced Another Country on the cover of their studio album, Our Favourite Shop. Another Country is an intensely English film, with multiple layers, exposing the contradictory nature of Englishness and what it means to be English, themes also explored by writers such as Patrick Hamilton, Elizabeth Taylor and Elizabeth Jane Howard. Haunting, elegiac and spiky. Despite the period gloss.

Another Country (1984) is available to watch via various DVD editions, although, surprisingly, it doesn’t seem to be available on instant digital download. But somebody has stuck up a quality recording (complete film) on YouTube.

You've just been reading a newsletter for both free and 'paid-for' subscribers. I hope you enjoyed it. A BIG thank you to all those of you who have signed up. Appreciated.

Two options:

The Friday morning newsletter is available on a ‘paid-for’ subscription with a 7-day free trial- which will also give you full access to the Luke Honey WEEKEND FLICKS. archive. Over time, this should build up into an invaluable resource.

The Sunday morning newsletter is for both free and paid-for subscribers (i.e. everybody). Take your pick. Either subscription’s a good bet.

So tune in for next weekend’s film recommendations. I’m in an 80s mood and there’s plenty to choose from.

In the meantime, have a relaxing and cinematic Sunday…

Ah the eighties, glorious on one hand , dark and pretty depressing on the other, depending on which side of the income bracket you settled in. Great piece , very enjoyable reading.

Great write-up Luke. Thank you. Saw the play, at the West End transfer. Think the London theatre was as strong the British film industry during the early 80s, which you rightly pin-point as a golden age. And clearly a close relationship between the two.