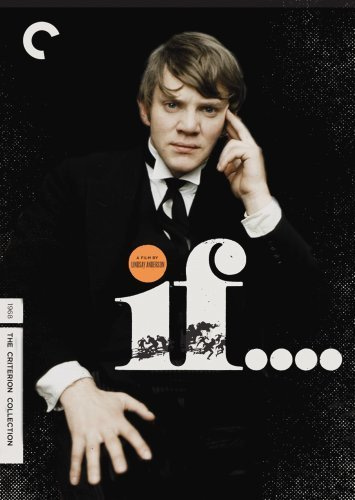

If.... (1968)

"Markland, warm my lavatory seat..."

The thing I hate about you, Rowntree, is the way you give Coca-Cola to your scum and your best teddy-bear to Oxfam and expect us to lick your frigid fingers for the rest of your frigid life...

I've been itching to write about If.... (1968) — Lindsay Anderson's amusing, surrealist, and creative take on the English public school system. There's so much to say. For between 1979 and 1984, I attended Cheltenham College, the institution which provided most of the imaginary school's location and, to some extent, also helped shape the script. The director, Lindsay Anderson, had been there too, and as the story goes, he approached the headmaster of his old school, David Ashcroft, with David Sherwin's script and a cock 'n bull yarn about “doing something along the lines of Tom Brown's Schooldays.” So Cheltenham's magnificent Victorian Gothic architecture provided a suitable aesthetic backdrop.

Cheltenham College was founded in 1841 'for the sons of those moving in the circle of Gentleman, no retail trader being under any circumstances to be considered’ — rapidly becoming one of England's leading army schools, polishing boys for Sandhurst, Woolwich and the distant lands of Empire. If Papa didn’t cut the mustard, tough titty. Here boys on the army side ('Military' as opposed to 'Classical') might learn mathematics, chemistry, drawing and Hindustani. Fourteen Old Cheltonians have won the Victoria Cross. And during the First World War, 675 Cheltenham boys met their deaths, 19% of the 3,541 who served; a terrifying statistic. For Cheltenham was the first of the Victorian public schools, a group which includes Marlborough (1843), Wellington (1853) and Haileybury (1862), combined, memorably, by Paul Scott to form the imagined public school, Chillingborough, in The Raj Quartet.

The new Victorian schools were a response to a new, fast-rising, pushy, aspirational and Empire-building upper-middle class, tempered with fashionable, prim Evangelism, a bullish mix of both old and new money — an impecunious younger son of landed gentry, say, might marry the pretty daughter of a rich solicitor and enter Cheltenham Society via a grand, stuccoed townhouse in a voguish terrace. And alongside the new schools came the zeal of the great reforming headmasters, the influence of Rugby’s Dr. Arnold (Tom Brown’s headmaster) — and his subsequent followers, with their ‘Muscular Christianity’: compulsory, organised games (a handy alternative to disorganised wanking); routine chapel, cold showers and runs, discipline and athleticism, the esprit de corps of the house system, and the school Rifle Corps (then sort of nationalised, and given official government recognition to become The Officer Training Corps in the Haldane reforms of 1908): gentlemen factories producing team-players, for the army, politics and the colonial civil service — and latterly, in our own century, the slick, corporate life of big business: even if the antiquity, traditions and slang of the new Victorian schools were essentially fake, with their spanking new Gothic settings, ‘monastic’ stained glass and ‘medieval’ cloisters and quads, which in the late 19th century, would have been only thirty or forty years old, the same distance today, say as the 1980s.

In the sixth form, I became obsessed with If.... (1968) (there was a creaky VHS recording doing the rounds of my House), siding with the Sten guns on the Chapel Roof (actually the roof of the Victorian chemistry laboratories, intersecting the Quad). And somehow, the school in If.... (1968) merged with the Cheltenham College of the early Eighties — partly because of the visuals, but also because of the shared terminology. The sweatroom (the spartan junior house common room), the Red Book ('All boys of College are forbidden to partake in sweepstakes, betting, gambling or pools'), the shacks or, in the case of Christowe, pits (studies); Matron's Orderly (i.e. fag), a toisie (a wooden desk cum chest of drawers), a chit (written permission to enter town), the gut (a boy who showed too much visible effort), the Pot (the headmaster), not to be confused with house pots (inter-house games cups) and the horizontally striped rather 1860-ish ribboned bow-ties, the Corps, with its puttees and double cap badge — front and back — to commemorate the Glorious Glosters' back-to-back stand in Egypt in 1801; Widor's Toccata on the magnificent Harrison & Harrison organ, promoted in the College prospectus, somewhat optimistically, as 'possibly the finest instrument in the West Country.’

The first years were hell on earth. I can remember being more frightened of the prefects than I ever was of the masters, despite housemaster beatings, spending much of my time on satis, i.e. 'deemed unsatisfactory' or working off sinners, which meant polishing a Cadet Under Officer's boots or cleaning the carpet of a prefect's shack with a 1950s hoover, of which only three existed in the House. Sometimes, boys slept with them overnight — hugging them amongst the army blanket and iron-framed bed — so that they could clean their sections before breakfast. Lack of team spirit — that was the crime. Letting the side down. A preference for the Art Room over Kipling's 'Flannelled Fools and Muddied Oafs'. My housemaster (R.N. Rtd.), alas, found me somewhat ‘aloof’ as he explained to my long-suffering parents in a written report. Failing to cheer at a match, that was the sin — for which I was punished. As Rowntree tells the boys of College House: “Help the House and you will be helped by the House… We don’t intend to carry passengers.” And it was the same with friends’ parents, a friendly chat on College (cricket) Field might go something along these lines:

Keen Father: What team are you in, Luke?

Luke: None.

Keen Father (genuinely flummoxed): But you like Rugby, don’t you?

Luke: No.

Keen Father: But you play cricket or row, surely?

Luke: I scull, yes…

Where was that elusive House Pots bow-tie? The last two years, on the other hand, were terrific. Civilised, grown-up, and rather wonderful — I now look back on those formative years with immense nostalgia. The teaching (especially in the English department, headed by poet, Duncan Forbes, and T. S. Eliot aficionado, T. S. Pearce) was excellent. My final shack, which I decorated with a late 18th century Reynolds mezzotint (found in a junk shop on the Suffolk Road), looked out over a croquet lawn. As with Lindsay Anderson, it explains my ambivalence.

For Anderson, strangely, enjoyed his time at Cheltenham. He had been Senior Prefect and Under Officer in the Corps. You might even say that he thrived on it, the man was known for wearing the cerise and black stripe of the Old Cheltonian tie — which is curious, as understandably, having seen the film for the first time, many critics assumed If…. (1968) to be some sort of political attack on the Public School system. After all, the beating scene is more than brutal. But it's more complicated than that, I think. Life usually is.

So what’s the film about? One might describe it as a surrealist take on rebellion, framed within the context of a traditional English boy's public school, which is then used as a sort of metaphor for British society in general. And my God, you're on the rebels' side — or at least I am: even now, in Late Youth, a little bit of me with Mick (Malcolm McDowell) & Co., mortar and Sten, still, as they gun down the turgid schoolmasters, pompous parents and bullying prefects (Whips) from the roof of the chapel. I find these last moments deeply moving, along with several other sequences: the bewildered, bespectacled, bachelor House Tutor, Mr. Thomas (Ben Aris), sitting alone in his lonely bedsit (in black and white): "You can see the chapel spire when the leaves fall"; the adolescent sex scene, amongst bottles of rancid malt vinegar and chipped formica: "Look at me. Look at my eyes. I'll kill you. Sometimes I stand in front of the mirror and my eyes get bigger and bigger. And I'm like a tiger. I like tigers….", the nerdy boy, Peanuts (Philip Bagenal), observing the Universe (i.e. the outside world) from his shack window after ‘lights-out’:

Space, you see, Michael, is all expanding at the speed of light. It's a mathematical certainty that among all those millions of stars, there's another planet where they speak English…

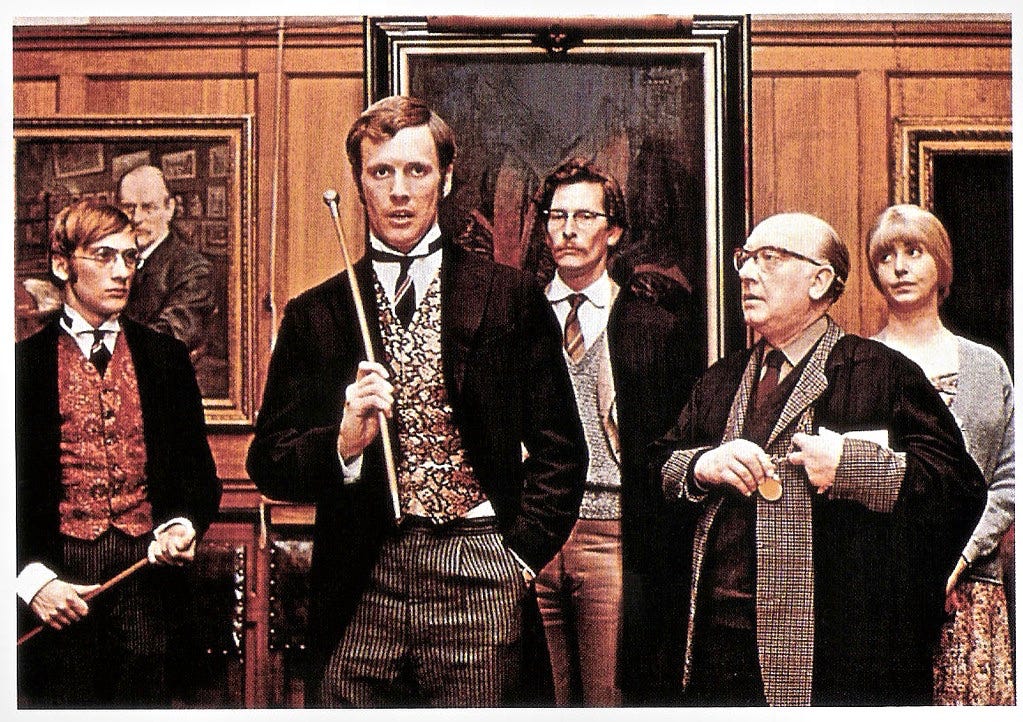

For Anderson meant it not as an attack on the Public School system, as such, but more of an intelligent and surreal satire with amusing undertones — and for those of us with a twisted black humour, it's almost hilarious. The Crusaders, Mick Travis (Malcolm McDowell), Johnny Knightley (David Wood) and 'Wally' Wallace (Richard Warwick) lead a rebellion against the Whips (i.e. prefects), Head of College and elegant schweinehund, Rowntree (brilliantly played by Robert Swann), general's son, Denson (Hugh Thomas), and the masters: housemaster, Mr. Kemp (Arthur Lowe), headmaster Peter Jeffrey and kinky Chaplain, (Geoffrey Chater), who rides out to Corps Manoeuvres on a grey, and twists Brunning’s left nipple in the very same spot where I used to sit for my English lessons.

Like Blow-Up (1966), If.... (1968) is one of those cult films which thrives on rumour and hearsay: the black-and-white sequences chosen in place of Eastmancolor, actually, more because of problems lighting the cavernous space of Cheltenham's Victorian Gothic chapel than any intellectual decision. Any public schoolboy worth his salt will claim that If… (1968) was filmed at their own institution. It wasn't — although the refectory, dormitory and beating scenes were filmed at Aldenham School, in Hertfordshire — a wise decision on Cheltenham's part.

In my all-time favourite moment, which again, I find deeply moving, the boys steal a motorbike, opening it up on the Cheltenham to Tewkesbury road: a glorious, exhilarating montage of visuals, sound and music, which somehow encapsulates the spirit of freedom (away from the repressed confines of the school), danger and rebellion; yet with a gentle English lyricism so typical of British cinema in the late 60s and early 70s. The sequence ends with a fanciful seduction of an Irish girl in a ramshackle Greasy Spoon cafe — alas, now demolished, but rumoured to have been on the Tewksbury road; subsequently identified by film buffs as somewhere in Bedfordshire. Marc Wilkinson's soundtrack is genius, too — especially in the motorbike sequence, hardly ever mentioned by fans of the film: combining the avant-garde with an English classical sound.

So there you go. Lindsay Anderson's If…. (1968). It’s a mere taster, this, only enough to get started. But it’s a truly wonderful film — a significant achievement — one of the greatest British films of the 1960s. It's also up there in my all-time Top Five favourite films and if you haven’t seen it, I hope this post will, at least, inspire you to do so. I watched If…. (1968) on DVD, and there’s a nice quality download available via Amazon Prime Video. There’s also a film buff’s guide by Mark Sinker, published by the BFI in their Film Classics series.

Here’s a quick word about the paid subscription, which costs £5 a month or £50 a year. Paid subscribers get their own special post on Friday mornings, special additional posts and access to the entire archive — now running at some 138 films. The Sunday morning posts are free and can be read by anybody and everybody. Thank you for subscribing and I would like to wish all my readers a very Happy Easter.

All I can say is I was Radley 76-80; but I have always wondered what on earth this film means to someone who “wasn’t there”!

A cracking read - haven't seen the film , but will do so now. Your conversation about sport at school made me think about Logan Mountstuart in William Boyd's novel 'Any Human Heart' when as a schoolboy who loathes sport, he makes sure he's a wide fielder in cricket so he can be left alone to look at the sky instead.