And so we come to Part Two of our Roger Moore Bank Holiday Special. To read Part One, The Man Who Haunted Himself (1970), please click on the link.

Not so long ago, favourite, feel-good films appeared on British television channels with a regular frequency. Bank Holiday films, I like to call them. Films you've probably seen so many times that, somehow, they've become ingrained in a nostalgic, collective memory. A memory of Bank Holidays past. Let's make a list. From the top of my head there’s My Fair Lady (1964), Mary Poppins (1965), The Sound of Music (1965), The Blue Max (1966), Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (1968), The Railway Children (1970), Young Winston (1972), Murder on the Orient Express (1974), The Eagle Has Landed (1976), and, of course, Bond. And if I had to point a long, black-gloved finger at the Bonds with a Bank Holiday vibe, it would have to be— roll of drums— 1) the superb On Her Majesty's Secret Service (1969), which we covered in a previous post, 2) the Guilty Pleasure that is Guy Hamilton’s Live and Let Die (1973) and 3) the even more Guilty Pleasure that is The Man with the Golden Gun (1975).

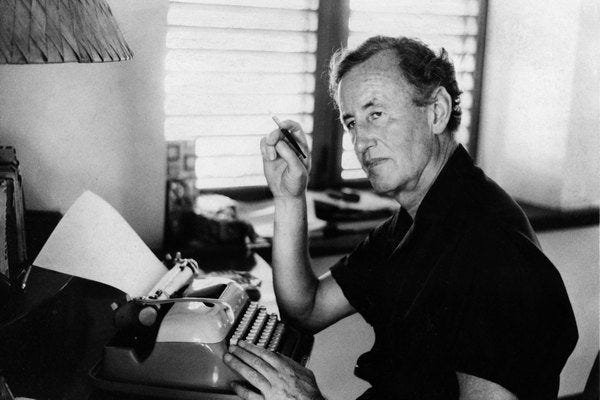

As you've probably gathered, I'm a fan of Roger. This goes back to my days at a Prep School in the Edwardian Mock Tudor paradise which is Gerrards Cross, about the time of Live and Let Die, circa 1973. One day, a new boy— surname Moore— turned up in the playground, a saturnine, chubby, rather good-looking boy, who suddenly announced “My Daddy swims in tanks with sharks”. The following day, Moore trumped it with a definitive “My Daddy is James Bond”. This was met with incredulity, and from memory, scuffles, and— I regret to tell you— a fight. I told my Mother what had happened. She put down her Fairy Liquid, slowly unrolled her Marigolds and gave me a curious look. "Well, maybe he is”, she said. About a week later, an open, silver-blue Rolls-Royce Corniche pulled up at the school gates, and there at the wheel was, yep, you guessed it, ol' 007 himself. In a smart, blue velvet-collared overcoat. Never before, or since, have I eaten such humble pie. Oh, to join the queue of cap-doffing, snivelling Prep School urchins, genuflecting at the great man's feet! All for a scribbled autograph on a miserable scrap of school paper. Roge raised an eyebrow. “Your pen doesn't work”. That’s all he said. Oh, sweet revenge.

Live and Let Die was the eighth film in the Bond franchise, although it was actually Ian Fleming's second book, published in 1954. You know the plot, as like me, you've probably seen it endless times on a rainy Bank Holiday Monday. It's the esoteric one. Bond's on the trail of a Harlem-based drugs operation, which inevitably leads to a diabolical Voodoo cult in the imaginary island of San Monique, presumably based on Haiti. And there are rubber snakes. And like Diamonds Are Forever (1971), Live and Let Die is set in the Americas. Union problems caused this, back in Blighty. Easier to film in America, which also means, curiously, I think, that Live and Let Die, visually, looks like one of those Aaron Spelling television productions (Charlie's Angels)— somehow lacking the cinematic feel of, say, Goldfinger (1964) or On Her Majesty's Secret Service (1969).

Live and Let Die, of course, is very much a product of its time. When the dubious double influences of blaxploitation and the occult were toute le rage. It's very Seventies, made only two years after Diamonds Are Forever (1971). Yet Live and Let Die might be from a different planet. Talking of the occult, Mark Gatiss and Matthew Sweet made a brilliant Radio 4 feature (Black Aquarius) on this very subject, about how esoteric themes dominated pop culture in the 60s and 70s, a time when Dennis Wheatley paperbacks featured a goat's head and a prancing flame babe— actually not at all unlike the opening titles of Live and Let Die, set to Paul McCartney's brilliant and edgy soundtrack, which somehow makes the film into something else. It's one of the best of the Bond themes. Take that away, and you've got something entirely different.

All the arcane stuff is very Fleming. Reminding me of the portraits of Sir Francis Dashwood and the Hell Fire Club at Blade's, mentioned in Moonraker (1955)— inspired by the Society of Dilettanti portraits, now hanging on the wall of Brooks's— and Blackbeard's treasure in Live and Let Die (1954); Silver Doubloons, the romance of the Spanish Main. Fleming nicked the Voodoo bits from Patrick Leigh Fermor's The Traveller's Tree (1950). And Bond has to be the world's worst, most indiscreet secret agent. He walks into Harlem's Oh Cult Voodoo shop and buys a stuffed alligator ("I'll have this gift-wrapped") wearing an RN tie (tight knot) and the double-breasted dark-blue overcoat. Despite the transatlantic accent, he's hardly incognito. Moore's Bond is not only as smooth as polyester, he's actually rather facetious. An inevitable quip at the ready. Girls, if Bond tried to pick you up in real life (hairspray and a tasselled loafer), either propping up The American Bar at The Savoy or sitting next to you at a London dinner party, what would your reaction be? Be honest. Does ‘tosser’ spring to mind?

Which takes me to Jane Seymour (Solitaire). I think this was her first film, although she had previously starred as Emma Callon in The Onedin Line. And she's as sweet as apple pie, twenty years old, barely out of a nice private school in Hertfordshire, while 45-year-old Bond— ahem, is almost old enough to be her biological grandfather. Which, I suppose, to a modern audience, seems a trifle unsavoury. But hey, it's 1973, ain't it? A different time and a different place. Yet three years later, in The New Avengers (1976) they cast cockney macho-man, Gareth Hunt, for this very reason, as a foil to Steed. Poor Gambit, however hard he tried, Purdey always seemed far more interested in the urbane 54-year-old Steed. As they say, two's a company, three's a crowd.

Anyway. Solitaire is Mister Big's girl (aka Dr. Kananga, played by American actor, Yaphet Kotto in a rubber mask) and she tells fortunes. The splendid 007 tarot pack (I refuse to call it a deck) was designed by the Scottish folk-artist, Fergus Hall. Salvador Dali, who had initially been commissioned to make one for the film, failed to complete his pack in time for the production. You can still buy it. I want one. And there's a toe-curling moment (oh, cringe!) when devious Mister Bond somehow manages to switch the pack, which persuades Solitaire— by means of esoteric prophecy— poor lamb, to jump straight into the commander’s bed. God knows how Bond manages to rustle up a trick tarot pack in time. This remains one of the film's great mysteries.

Alongside the fact that the Glastron speed boats just happen to be fuelled and left running, keys in the ignition, ready to go. The speedboat sequence, set in the Irish Bayou wetlands some thirty miles from New Orleans, is terrific, especially when you realise that it was made long before the curse of CGI, and despite the presence of one Sheriff Pepper (Clifton James), the irritating Louisiana policeman, who, alas, like a bad smell which won't go away, resurfaces in The Man with the Golden Gun, where by mysterious coincidence he just happens to be on holiday in Bangkok.

Is Roger Moore the definitive Bond? No. Raised eyebrow aside, that honour must go to Sean Connery, George Lazenby or, rather unfashionably, the Shakespearean Timothy Dalton. In the sense of Bond as imagined by Ian Fleming. And thinking about it, most appropriately, Bond’s raison d’etre meets its demise in Live and Let Die, or should it be Die and Let Live? By 1973, Bond is dead, kaput. R.I.P. Mister Bond. The mid 70s, Watergate, the Oil Crisis, Terylene and the final years of the Vietnam War made the world a very different place from Ian Fleming’s stiff-upper lip, ‘Made in England’, fag-end of Empire of the 1950s. Not, of course, that any of this should put you off. In the right mood, Live and Let Die is fun, highly entertaining, and deliciously and wickedly politically incorrect. Vaguely titillating, too. Perfect fodder for a cocktail and a rainy Bank Holiday weekend. That said, arcane stuff aside, it ain’t Ian Fleming. Although Bond, at least, does get to wear a feather cape.

Live and Let Die (1973) is, of course, available to watch in various ‘Special 007’ DVD and Blu-ray editions (that’s sinful luxury) and there’s a digital download for Amazon Prime Video members which you can watch in exchange for a handful of golden nuggets.

You've just been reading a newsletter for both free and 'paid-for' subscribers. I hope you enjoyed it. Thank you to all those of you who have signed up. Really appreciated. To view the other films we’ve covered so far, please go to the Luke Honey WEEKEND FLICKS. archive. ‘Paid for’ subscribers get two weekend film recommendations, access to the entire archive and the ability to comment. By the end of the year, there should be over 100 film recommendations.

I will be back next Friday. In the meantime, I hope you have a relaxing and cinematic Bank Holiday. So why not settle down with a cocktail and a film? I can’t think of anything more civilised…

Timothy Dalton is the most faithful incarnation of Bond, true. But who can resist The Spy who loved me? Best Bond song ever by the way... Carly Simon outdid herself!

It’s a competitive field but “Names is for tombstones, baby” is one of my favourite lines of dialogue in all of cinema. Especially as a response to the iconic “The name’s Bond, James Bond”. Also, “Take this honky outside and waste him” shows that Mr Big isn’t pissing about.