Welcome back to WEEKEND FLICKS. This Sunday, in our regular post for free subscribers: Rogue Male (1976) — based on Geoffrey Household’s cult novel of 1939 and now remastered by the BFI on DVD and Blu-ray. The psychogeographer’s thriller.

The behaviour of a rogue may fairly be described as individual, separation from its fellows appearing to increase both cunning and ferocity.. These solitary beasts, exasperated by chronic pain or widowerhood, are occasionally found among all the larger carnivores and graminivores, and are generally males, though in the case of hippopotami, the wanton viciousness of old cows is not to be disregarded.

Geoffrey Household, Rogue Male (1939).

I came across Rogue Male (1976), the made-for-television BBC film, while researching Friday’s post on The 39 Steps (1935). And saw it for the first time last night. I love discovering new things; that’s very much what WEEKEND FLICKS is all about, and this was a new one on me, altho’ Geoffrey Household’s brilliant — and frankly, strange — thriller (as with John Buchan’s The Thirty-Nine Steps, written on the eve of a great war), remains a favourite. We ‘did’ it at school, and the 1970s Penguin paperback cover, featuring Hitler as seen through the assassin’s telescopic sight (rediscovered via the internet archive), brought back the memories flooding back.

Like the original novel, described by the author as “a sort of bastard by Stevenson out of Conrad”, Rogue Male (1976) is a brilliant — and strange — film. And I mean that as a compliment. Despite its originality, we might place Household’s book within that appealing genre of British gentlemanly thrillers. Richard Usborne wrote about this in his equally brilliant and entirely readable literary dissection, Clubland Heroes (1953), which comes with my recommendation: ‘A nostalgic study of some recurrent characters in the romantic fiction of Dornford Yates, John Buchan and Sapper.’ As with The Thirty-Nine Steps (1915), Rogue Male (1939) features a gentleman amateur on the run, an influence, clearly, on Frederick Forsyth’s ruthless assassin in The Day of the Jackal, and to a lesser extent Ian Fleming and John Le Carré. And Buchan, himself, must also have been influenced by Robert Louis Stevenson’s Kidnapped (1886), heroes (David Balfour and Richard Hannay), implicated in crimes they did not commit, both pursued through a hostile Highland landscape.

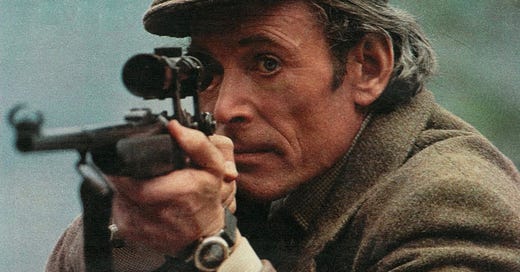

In Household’s original thriller, an unnamed English gent stalks an unnamed European dictator — clearly Adolf Hitler, which Household later confirmed, although, at the time, he felt that it was safer (for political reasons) to leave this unspecified — and fails to kill him. As with so much of the book, this actual event is pretty ambiguous, and when our hero is picked up by the Gestapo and tortured, his explanation may be genuine: “I was bored. I’m a sportsman, Sturmbannführer; I did this only to see if I could — no more than that; as a wager against myself” — or words to that effect. It’s a sporting stalk. So in the film, the unnamed sportsman becomes Sir Robert Hunter Bt., a huntin’, shootin’, fishin’ aristocrat, played brilliantly by Peter O’ Toole with a languid, upper-class insouciance — and it’s also clear that he’s out to revenge the death of his appealing girlfriend, Rebecca (a lovely performance from Cyd Hayman) — who’s clearly Jewish and possibly some sort of a British agent; executed by the Nazis.

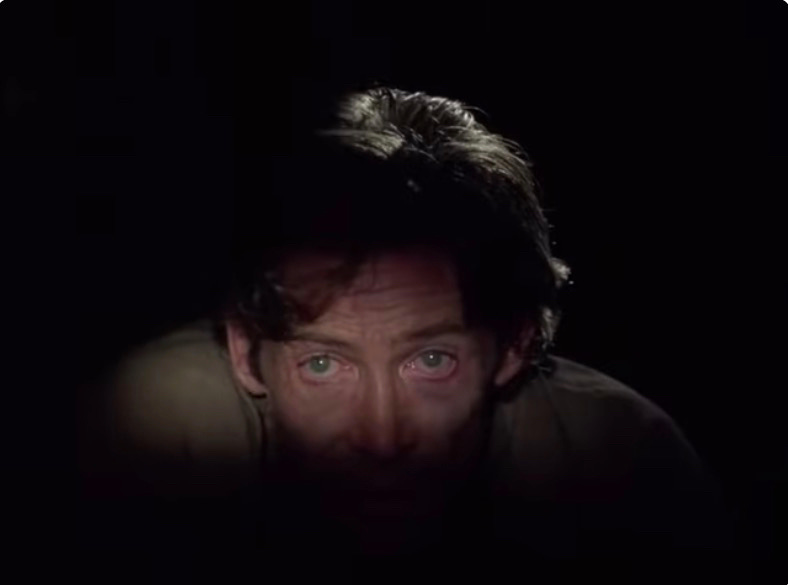

There are some differences between the book and the film. In the book, the protagonist has a cold, clinical ambiguity. In the film, Sir Robert is more emotional, or that, perhaps, is the wrong word — ‘I am ruled by my emotions, though I murder them at birth’ — but he’s certainly damaged. And then, back in England, Sir Robert has to go on the run, pursued by German agents, the hunter becoming the hunted, and goes to ground, using all his skills as a countryman and sportsman, the author of Rough Shooting (ironically, a valuable handbook for the Nazi stalkers), like a badger, fox or stoat, in the Dorsetshire countryside. The undulating downs, the long barrows, sunken lanes and copses, and the topography of Dorset become an essential part of the book and the film’s raison d’être. There’s a psychogeographical element, a feel for the English landscape; elevated in the film by Christopher Gunning’s fabulous score, which sounds very much like Ralph Vaughan Williams — so much so that, for a few moments, I thought the music was by Ralph Vaughan Williams. The cruel demise of a little black cat, incidentally, triggers Sir Robert’s understandable murderous rage. I mean, if you want to antagonise an Englishman, there’s no better way to do it.

John Standing's in it too, which is always a good thing — as Sir Robert's pursuer, the caddish Major Quive-Smith: in the book, a German posing as an Englishman (brand new checks), in the film more of a sinister Mosleyite, or an agent of the British Union of Fascists. And Harold Pinter! He's in it too — in a surprise appearance as Sir Robert's Jewish, urbane pin-striped solicitor, with a Lincoln's Inn set, waistcoat and watch chain. And Alastair Sim, in his last film performance, as Sir Robert's uncle, a florid Earl, a member of the cabinet, who, reading between the lines, is prepared, along with the rest of the establishment, to make a deal with Hitler. In 2013, Robert Macfarlane wrote a lovely piece for The Guardian, Rereading Geoffrey Household’s Rogue Male, in which he sets out with Roger Deakin, the film-maker, environmentalist and author, to explore Rogue Male’s Dorsetshire landscape and to track down the 'likely location of a deep lane in which Household's hero… goes to ground, and where the novel reaches its extraordinary climax':

The pages included a description of the lane. It was a "sandstone cutting" or holloway that ran over "the ridge of a half-moon of low, rabbit-cropped hills, the horns of which rested upon the sea". The cutting was "a cart's width across" at its base, it was choked with "dead wood" and jungled by shoulder-high nettles, and its entrances were barred by "sentinel thorns". "Nobody but an adventurous child would want to explore it," noted Household.

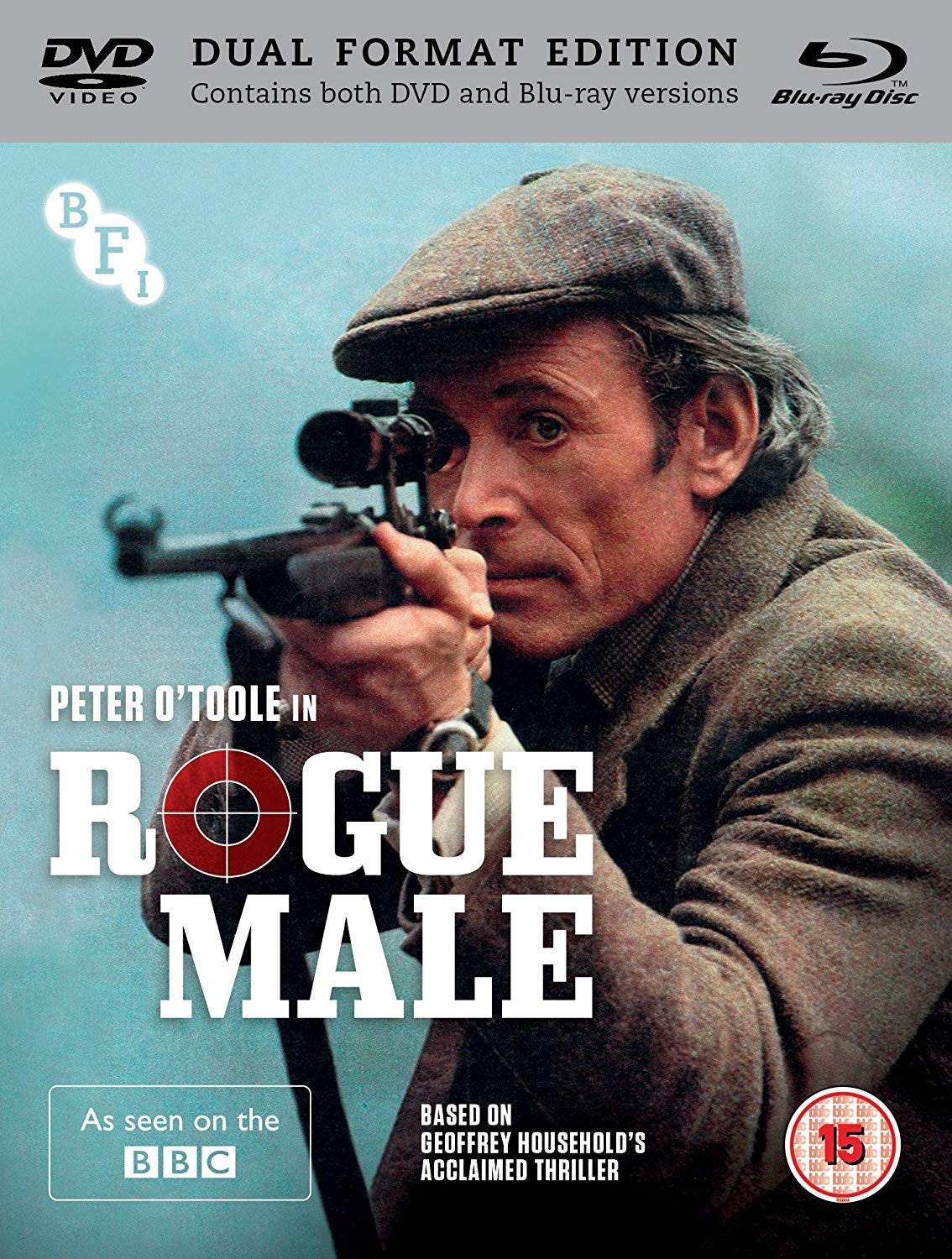

As you’ve probably gathered, I like Rogue Male — both the book and the film very much indeed. Shot on 16mm, the BBC film has now been remastered by the BFI and is available on a tasty DVD/Blu-ray combo, featuring interviews with the director, Clive Donner; screenwriter, Frederic Raphael, and a selection of Eva Braun’s home movies. It was, of course, a television production when first broadcast on a September evening in 1976, and to a younger audience, reared on CGI and slick, homogenised digital processing and colour correction, may now seem crude — although, personally I find Clive Donner’s direction, Brian Tufano’s cinematography and Frederic Raphael’s pithy script an artistic triumph, taking into account the considerable budgetary constraints that the BBC faced at the time. This is not your usual, bog standard run-of-the-mill BBC Play for Today — as good as some of those ‘plays’ can be. And for Peter O’Toole, the role of Sir Robert Hunter remained his all-time favourite part. I’m also a fan of Frederic Raphael, who also wrote the screenplays for a cluster of favourite films: John Schlesinger’s Darling (1965), starring Dirk Bogarde and Julie Christie; Far From the Madding Crowd (1967), Stanley Donen’s Two for the Road (1967), which we covered last year; the BBC television series Oxbridge Blues (1984), and Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut (1999). Curiously, and according to that trusty sword of accuracy and truth, Wikipedia, the BBC also distributed Rogue Male for international cinema release, but industrial and legal issues soon thwarted this admirable plan and the film was pulled from British cinemas.

So there you go. Hopefully, I’ve written enough to tempt you to test the waters. I watched Rogue Male (1976) on YouTube, where an enlightened soul has posted a quality recording, and, for those of you with a ‘smart’ television set, this is eminently watchable. Otherwise, the BFI have released a remastered dual-format edition in both DVD and Blu-ray, which comes with a host of extra goodies.

If you liked this piece, why not subscribe?

🗓 Free subscribers get a new post every Sunday morning — part memoir, part film criticism, part social history.

🔐 Paid subscribers receive the full version every Friday, plus unlimited access to the complete archive — now featuring 146 film recommendations (and counting), films which have that certain je ne sais quoi.

📬 It’s £5/month or £50/year, and your support helps keep the projector running.

I’ll mention Fritz Lang’s 1941 adaptation MAN HUNT, which is quite a film.

A rare favourite novel decently filmed. Thanks for the reminder, Luke!