The Charge of the Light Brigade (1968)

"There My Lord! There is your enemy! There are your guns!"

Half a league, half a league,

Half a league onward,

All in the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.

"Forward, the Light Brigade!

Charge for the guns!" he said:

Into the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.Alfred Lord Tennyson (1809-1892).

Tony Richardson’s The Charge of the Light Brigade (1968) is a visual and aesthetic masterpiece; every shot framed beautifully. Yet The Charge of the Light Brigade (then the most expensive British film ever made) received muted acclaim at the hands of the critics: Richardson didn’t exactly help, describing his detractors as ‘intellectual eunuchs’ and refusing a screening. Readers of WEEKEND FLICKS will, of course, know their history. In 1854, Lord Cardigan led a semi-suicidal charge of Light Horse (Hussars, Dragoons and Lancers) against a battery of Russian artillery. Light cavalry were used for reconnaissance or skirmish; they were not supposed to attack gun batteries in a frontal assault. The Light Brigade suffered a 40% casualty rate.

The casting is to die for. Inspired. David Hemmings, Vanessa Redgrave, John Gielgud, Eric Porter, Jill Bennett, Peter Bowles and Alan Dobie — plus uncredited appearances from Laurence Harvey (as a Polish aristo) and the young Joely and Natasha Richardson (in the wedding scene). And, somehow, Trevor Howard is Lieutenant General James Thomas Brudenell, the 7th Earl of Cardigan KCB: the sex scene between Howard and Bennett is priceless. The Charge of the Light Brigade was made at the time of the Vietnam conflict. We explored this influence in the post on Oh! What a Lovely War (1969), released in the following year, with the anti-war mood prevalent in the late 60s: a sense of futility and a collapse in confidence, ‘Lions led by Donkeys’— which, I think, had as much to do with the breakdown of class barriers at that time; when, as distinguished revisionist historians have now shown us, the historical reality was somewhat different.

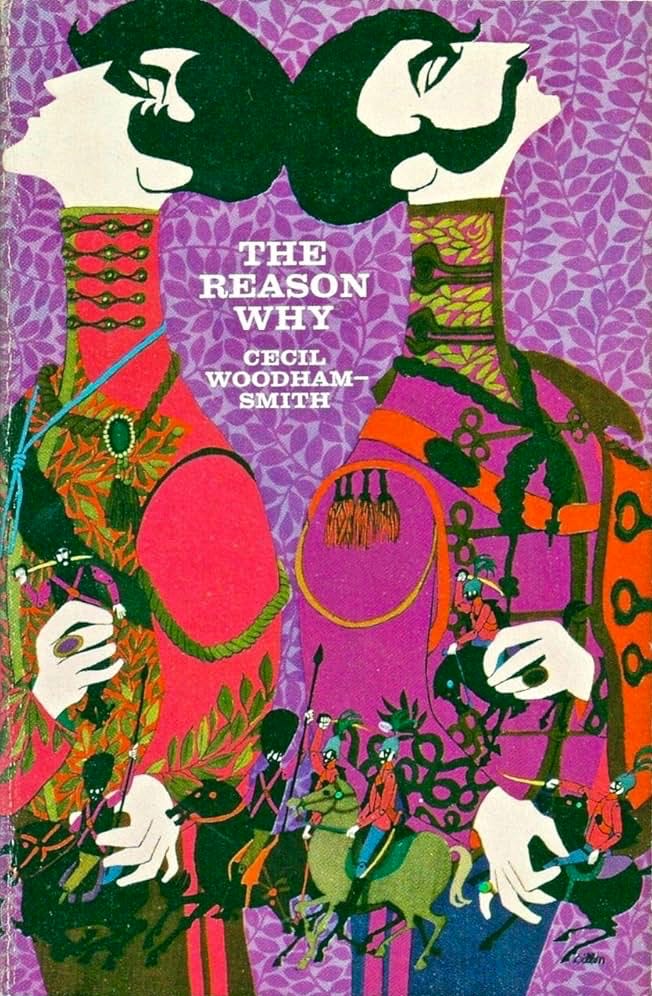

Richardson’s film is based on Cecil Woodham-Smith’s The Reason Why (1953), a beautifully written, stylish, engaging — and sometimes angry — work of narrative history, which some historians now consider flawed. Woodham-Smith sees the charge as less about individual guilt (a Victorian whodunnit, Lords Lucan, Cardigan or Captain Nolan?) and more a ‘sweeping condemnation of the English class system’ (until 1871, officers in the British Army purchased their commissions), fitting neatly into the late 60s narrative. Cardigan is condemned as ‘alas, unusually stupid’ when, as the military historian, Saul David, points out, this was not necessarily the case: you know, it’s that very English upper-class thing, sharpish brains hidden beneath huntin’, shootin’, fishin’ bluster — a landed mistrust of anything vaguely intellectual.

Anyway. For non-military-history-buffs, there’s plenty of action away from the front. And as much as I adore the 4 hours 19 minutes of Gettysburg (1993) or the 2 hours and 14 minutes of Waterloo (1970), I’m not going to inflict them upon you. There are tantalising shots of John Fowler’s Gothick Hunting Lodge in Hampshire, filmed, presumably, when he was still living there. Net curtains? Really? Julia Trevelyan Oman (the late wife of Sir Roy Strong) was the associate art director on the film, and the attention to historical detail, as you might expect, is superb. I’m a huge fan of Trevelyan Oman’s work: her designs for ballet (The Nutcracker and Frederick Ashton’s Enigma Variations) and for cinema, the grungy farmhouse in Straw Dogs (1971) and a High Victorian/Anglo-Indian sensibility for Jonathan Miller’s Alice in Wonderland (1966), which we covered in an earlier post. In The Charge of the Light Brigade (1968), as with Ridley Scott’s The Duellists (1977), the viewer is transported back in time, in this case to the mid-19th century, when the swells and the toffs dropped their aitches and talked about ‘wabbits’.

But again, we can overlook the historical boobs (the Lancers wear the cerise cherry-picker overalls of the 11th Hussars), and it doesn’t matter — that’s to miss the point. I’m not wringing my hands. The important thing is that there’s a feel for the mid-19th century, even if the ‘Color by DeLuxe’ can make the film look like a tinted postcard from 1906. But Richardson deliberately used camera and lighting effects to give his film the feel of a daguerreotype, and there’s a shot of Vanessa Redgrave against an ivy-clad brick wall (by a bridge) which reminds me enormously of the work of Victorian photographer, Julia Margaret Cameron.

It’s this period feel which is so often missing in our contemporary so-called ‘period’ dramas, partly, I suspect, because modern production designers feel that they have to make their own personal statement (the ‘me’ generation), to ‘make it current’, as Mr. Cowell might say on the dreaded X Factor, to ‘make it your own’ — to give history a ‘twist’. The recentish Netflix production of Rebecca (2020) is a case in point. Instead, give me the authentic BBC interpretation of 1979 starring Jeremy Brett as a more than plausible Maxim de Winter. Despite the budget lighting, the stagey direction, the dodgy makeup and the blurry 16mm ‘outdoors location’ photography. We can even forgive the Tudor radiator in Elizabeth R. (1971).

And look out for Richard Williams’ brilliant animations based on political and diplomatic cartoons from Punch and The Illustrated London News. In those days animations were drawn by hand. It took over a thousand animators and technicians to make Walt Disney’s Fantasia (1940). How many ‘Victorian’ cross-hatchings are there in an individual frame? The mind boggles! Williams also produced the Oscar-winning A Christmas Carol (1971) — by my book one of the greatest Christmas Carols ever made and one of the earliest film recommendations on WEEKEND FLICKS.

So there you go. Like Elvira Madigan (1967) or The Duellists (1977), The Charge of the Light Brigade (1968) is very much an aesthete’s film. There’s an excellent DVD from the BFI and it’s also available on Blu-ray and Amazon digital download. Light Brigade buffs might also like the 1936 version, starring Errol Flynn and David Niven, which, somewhat bizarrely, places most of the action in India, influenced by the success of The Lives of the Bengal Lancers (1935).

You’ve just been reading a newsletter for both free and 'paid-for' subscribers. I hope you enjoyed it. Thank you to all those of you who have signed up so far.

There are two options on Luke Honey’s WEEKEND FLICKS. Cinema for Grown Ups: ‘Paid-for’ subscribers get an extra exclusive film recommendation every Friday morning, plus full access to the complete archive — which is currently at film no. 97, and should list over a hundred films by the end of the year. It costs £5 a month (or £50 a year) — a bargain, frankly, when you compare it to a few cups of coffee, a packet of semi-legal gaspers, or a pint of beer in the pub. ‘Free’ subscribers get access to the Sunday newsletter, plus the ‘free subscriber’ films in the archive. Either option is a good bet. And when I get my act together, I’m planning to add a spoken voiceover (mine!) for paid subscribers.

I will be back on Friday. In the meantime, sit back, mix a Dry Martini — and have a relaxing and cinematic Sunday.

Surely the Cherrypickers were the 11th Hussars not the 10th ?

Let's cross our arms and join the dance - Prince Charming, Prince Charming, ridicule is nothing to be ashamed of!