The Go-Between (1971)

"You flew too near to the sun, and you were scorched..."

Certain books should be read in your late teens. Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms (1929) and A Moveable Feast (1964) immediately spring to mind; Brideshead Revisited (1945) is another. As is Donna Tartt’s The Secret History (1992) and Alain-Fournier’s Le Grand Meaulnes (1913). And to that elegant, elegiac, evocative list, I would add L. P. Hartley’s The Go-Between (1953)— in my opinion, a masterpiece. I first read the book when I was sixteen years old, in a lovely small hardback edition I discovered in a shabby basement bookshop in the backstreets of Cheltenham, with green boards and wafer-thin paper, and loved it from page one. As with The Great Gatsby (1925), it’s a book I return to year after year, if I can.

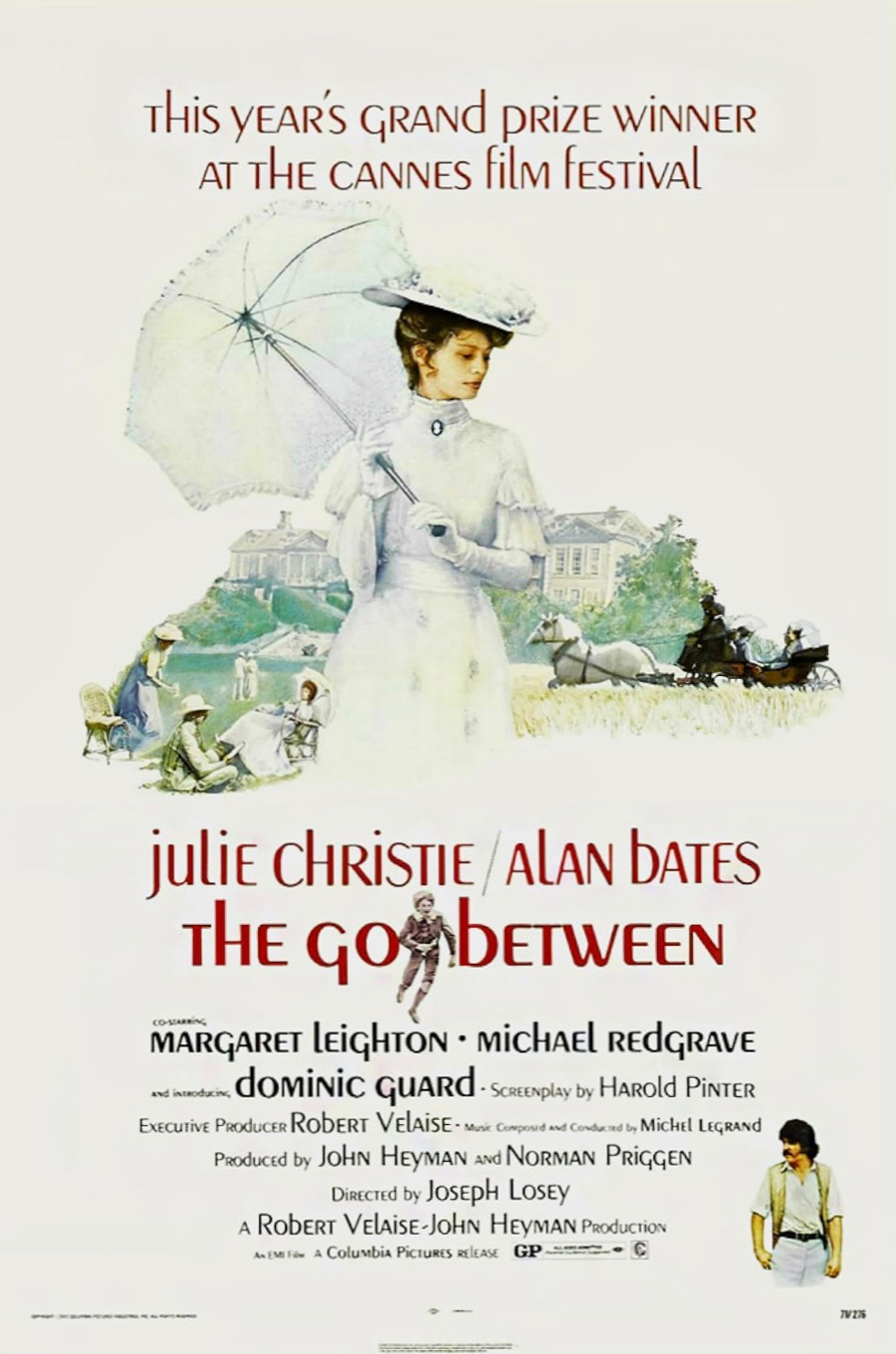

L. P Hartley is such a sensitive writer— I hesitate to use that overused cliché, underrated— but in this particular case, it might apply. The events of The Go-Between take place at Brandham Hall (a Norfolk Country House) in the July of 1900. A twelve-year-old boy, Leo (on the cusp of adolescence), acts as a clandestine messenger, running chits between Marian, a twenty-year-old upper-class beauty, and Ted Burgess, a manly local tenant farmer. As you know, that’s the plot, but of course, there’s a great deal more to it than that. According to Adrian Wright’s extensive biography, Hartley may have based Brandham Hall on the real-life Bradenham Hall, near Swaffham, where Hartley stayed at the invitation of a Harrovian school friend in August 1909. Joseph Losey’s film does Hartley’s novel more than justice. Harold Pinter’s script is superb, as is Losey’s picture— one of his very best, up there, I think, with Accident (1967) and The Servant (1963). Losey’s preoccupations with Time and the English class system are very much to the fore— as is his sense of place, exemplified by Losey’s stunning use of sound.

Like Leo (Dominic Guard), L. P. Hartley came from a middle-class background. His father was a solicitor, later the manager of a brickworks. They were of the Methodist persuasion. The savageries, vagaries, and subtleties of the English class system are something Hartley understands and writes about beautifully. The thing to remember, which isn’t, perhaps, clear in the film (and critics often overlook), is that the Maudsleys, the smart, fashionable upper-class family, don’t actually own Brandham. They rent it. It’s really the seat of the Winlove family, which means Lord Trimingham (Edward Fox). Mr Maudsley (Michael Gough) is a rich London Money Man— of ‘Princes Gate and Threadneedle Street’, which suggests banking. It also explains why the Maudsleys are so desperate to marry Marian (Julie Christie) off to Trimingham, whose landed, aristocratic family, presumably, has been knobbled by the agricultural depression of the last three decades of the 19th century. Nothing like marrying into money to sort out your finances.

Leo, on the other hand, might be described as lower-middle-middle class. A scholarship boy at his local prep school, destined for a grammar or a minor public day school. His father was some sort of Pacifist bank clerk— with little money, but bags of taste, a collector of rare, antiquarian books and an interesting old house (one of those charming village houses on a green?), which happens (at least in the book) to be called ‘Something Court’— and of course the snobby, arriviste Maudsleys assume that Leo comes from a far grander background. And there’s that bit in the book when Leo’s widowed mother packs his trunk for his stay with the Maudsleys and gets it wrong, partly from reasons of economy (actually not unlike Widmerpool’s overcoat in Anthony Powell’s A Question of Upbringing), so that poor Leo arrives at Brandham wearing a stuffy, tweedy Norfolk jacket, rather than the elegant linen summer clothes required for the sweltering heat. I find this desperately touching. For a prep school boy, there’s nothing worse than getting it wrong.

Losey’s films have a terrific sense of place. Kitchen taps drip onto stainless steel, schoolchildren play, shouts bouncing off tarmac; carriage clocks chime in the distance, jet airliners pass overhead, shadows race across summer wheatfields, reeds rustle in the wind, footsteps echo off the floorboards of Brandham Hall— actually, in the film, Melton Constable in North Norfolk, a magnificent Grade I listed country house built in the style of Christopher Wren.

One of the many beauties of England is the diversity of its landscape and architecture. The grey limestone of the Cotswold Hills surrenders to the warm red brick, clay and flint of the the Chilterns in the space of a few miles. Each county— however small—has its own identity. Norfolk, that most English of counties, is no exception, with its wide, open skies, undulating barley fields, ancient copses, Dutch gables and bleak, windswept salt marshes. For The Go-Between is the most Norfolk of Norfolk films, captured on celluloid by Gerry Fisher’s languid cinematography— when the great fields turn to the colour of straw, and the heat and dust throw up spectacular Harvest Moons. Two shots, in particular, grab me, summing up Losey’s sense of place. A lovely long shot of the park, with drifts of deer, set against the whistle of a distant traction engine. The second is a luminous moon in the night sky, seen by Leo from his bedroom window, with moody scudding clouds, creating a sense of magic, of mystical possibility— the astrological theme very much explored in the book. There’s a similar moment, funnily enough, in The Exorcist (1973), when Chris, the film’s protagonist, walks the streets of Georgetown on an autumnal Hallowe’en afternoon, set to Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells.

And Losey’s use of sound extends to Michel Legrand’s classically inspired soundtrack. I’m a huge fan of Legrand, in my opinion, one of the greatest of all film composers (up there with Ennio Morricone and Henry Mancini) and his music is used in cinema to great effect. Take away The Windmills of Your Mind from The Thomas Crown Affair (1968) and you’re left with something different. Take away the soundtrack from Les Parapluies de Cherbourg aka The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964) and well, you’re just left with Catherine Deneuve.

The Go-Between starts with a shot of raindrops splattering a windowpane, set to the opening bars of Legrand’s Variations for Two Pianos and Orchestra, a piano concerto in the Romantic tradition. This is elegiac, haunting stuff— followed by a sudden shift in time, a flashback to Leo’s arrival (in a dog cart, or similar) with the music turned up. It’s loud, sort of drowning out everything else, even, perhaps, to some extent the considerable visuals. Losey has been criticised for this, but I’m one hundred percent with him. Losey is the master of sound, the master of memory and time; the sound accentuates the memories of a lonely man (Leo in late middle-age) who suddenly, and strikingly, after a mental block of many years, remembers his childhood and the traumatic events of long ago.

Is Julie Christie too old to play the charming, but ultimately brittle and manipulative Marian, who, after-all, is only six years or so older than Leo? Yes, probably. She was thirty one. Does it matter? No. Not really. It’s a minor quibble in a film with terrific casting and performances all round— from Edward Fox as the aimable, easy-going aristocrat, to Margaret Leighton as the pin-sharp, socially ambitious mother, from Alan Bates as Ted Burgess, the hunky tenant farmer, (“bit of a lad, that Ted Burgess”), to, of course, the young Dominic Guard, cast brilliantly as the naive, vulnerable, innocent, intelligent and potentially neurotic Leo, a pawn in a grown-up world he doesn’t understand. Guard plays a similar character, albeit ten years older, in Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975), a film curiously set over the same summer of 1900. And Michael Redgrave puts in a marvellously sensitive performance as the older, damaged fifty or sixty something Leo, a successful, but ultimately sad and lonely bachelor whose entire life and raison d’etre may have been ruined by the events of that memorable summer. The summer of 1900. The cusp of the Old World and the New.

So far, I've been a little bit hesitant to include The Go-Between (1971) on the WEEKEND FLICKS film list— as it's one of my favourite films of all time, and I hope I’ve done it justice. It's up there in my Top Ten list. Alongside The Servant (1963), Sleuth (1972), Don't Look Now (1973) and Walkabout (1971). If you're one of those lucky people who have yet to see it (or to read the book), Mein Gott, there's a treat in store. And it would be a fine thing: to go back in time and start all over again. To read The Great Gatsby, Brideshead Revisited, or The Go-Between for the very first time. But like H. G. Wells, I would need to invent— and build— a time machine. That is something I would very much like to do.

I watched The Go-Between (1971) on DVD, a cheap freebie given away by The Sunday Telegraph, but it is, of course, available in various other DVD and Blu-ray editions, plus instant digital download via Amazon Prime Video (a bargain £3.49 to rent), and I expect, on various other digital platforms. Michel Legrand’s original soundtrack was released by CBS as an LP in 1979, in a desirable coupling with the Symphonic Suite from The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, and if you’re into vinyl, and have a record player, well-worth tracking down. And there’s a fascinating book about the making of the film, Christopher Hartop’s Norfolk Summer, The Making of the Go-Between (2011), which, from memory, I managed to find on eBay and comes with my recommendation.

A big thank you to all those of you who have subscribed. How are we doing? Time for a recap. I started Luke Honey's WEEKEND FLICKS. Cinema for Grown Ups, back in December 2023— inspired by those vintage indents for London Weekend Television. That feel-good feeling on a late Friday afternoon when boring, worthy old Thames Television handed over to the racier LWT. My bright idea (which occurred to me in the bath) was to recommend two films over the weekend, with the rule that all the films should be readily available, either on DVD, or preferably instant download. I know that these old films have brought me a great deal of pleasure over many years, and I’m hoping that I can inspire you to watch something you may have forgotten about, or sometimes, might not even have come across. As most of these films are no longer shown on television, the urge becomes more pertinent.

We're now heading for 500 subscribers, with 6,000 views (plus) over the last 30 days. It's bloody hard work (7.00 am sharp, a crawl to the computer, a cup of strong black coffee and calluses on my fingers), but I enjoy it immensely. We're currently on film no. 72.

So what do you get? There are two possibilities on WEEKEND FLICKS: 'Paid-for' subscribers get an extra, exclusive film recommendation every Friday morning, plus full access to the complete archive— which should list over a hundred films by the end of the year. It costs £5 a month (or £50 a year)— a bargain, frankly, when you compare it to a few cups of coffee, a packet of semi-legal gaspers or a pint of beer in the pub. 'Free' subscribers get access to the Sunday newsletter, plus the 'free subscriber' films in the archive. Either option is a good bet.

In the meantime, sit back, mix a cocktail— and have a relaxing and cinematic Sunday evening. And enjoy The Go-Between (1971). Even if you’ve seen it before. This one’s for keeps.

*The Go-Between* is a magnificent film: there’s something very trippy and unreal about it, like being in a groggy half-dream, unable to clear your head. Always makes me think slightly in that regard of *Picnic at Hanging Rock*. Woozy, heavy with sleep, other-worldly.

I just want to say I have enjoyed reading your stunning critique of the Go-Between almost as much as I loved the book and watching the film… and that is really saying something. You have summed it up exquisitely…