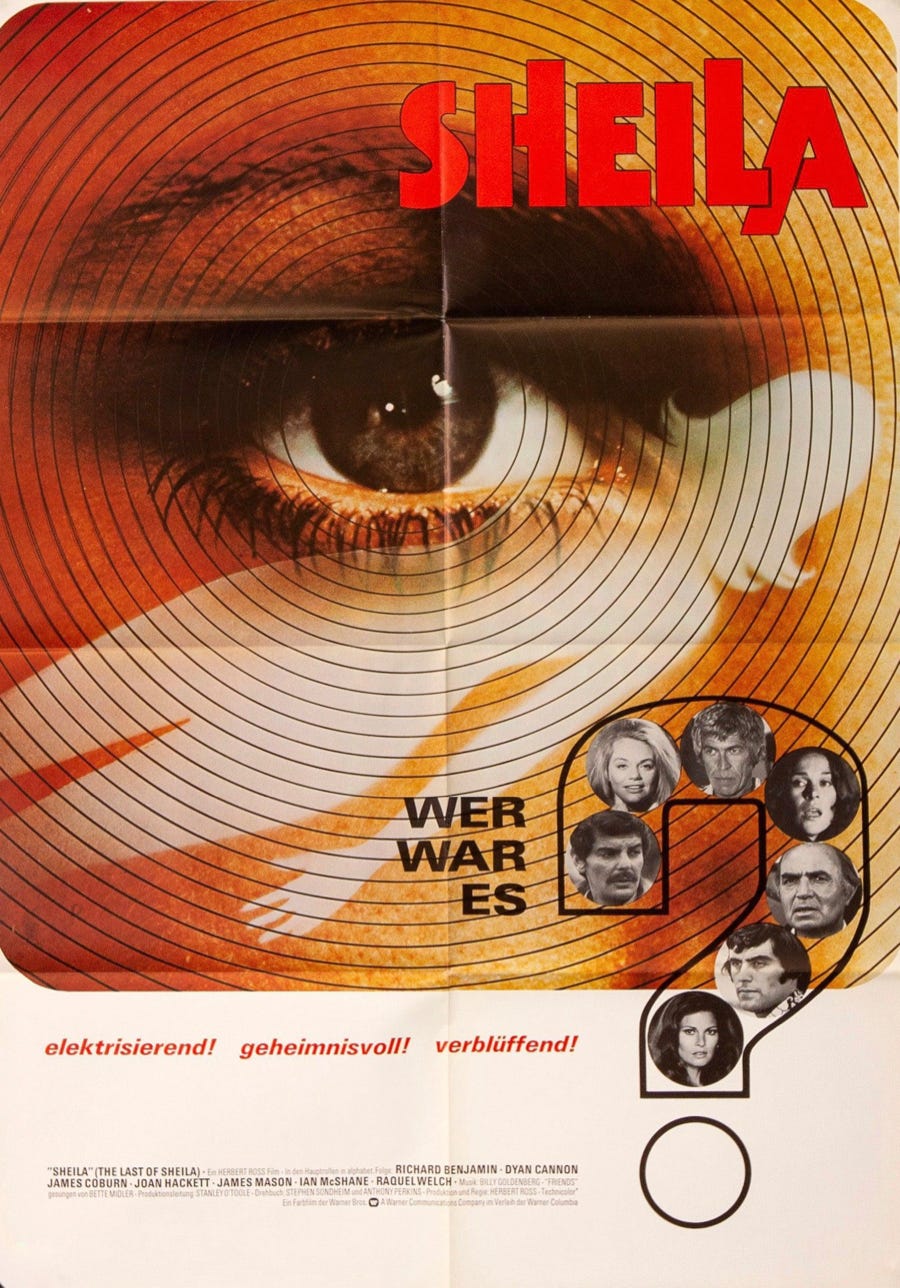

The Last of Sheila (1973)

Who did this room? Parker Brothers?

Mornin’ cinephiles. It’s time for sophisticated gamesmanship on Luke Honey’s WEEKEND FLICKS. Cinema for Grown Ups. First up is The Last of Sheila (1973), an entertainingly wicked, witty and waspish little number from the typewriters of Stephen Sondheim and Anthony Perkins, no less— yep, them of musical theatre and motel fame, which has subsequently gained a following amongst the cognoscenti. Herbert Ross is the director. Sondheim was a man obsessed with games and games playing. Anthony Shaffer’s Sleuth (1972), to some extent, is based on Sondheim’s notorious and ingenious house parties, in which his guests were sent off on cryptic and labyrinthal scavenger hunts. This also sets the tone for The Last of Sheila, although in the case of Sondheim’s real-life treasure hunts, the prize at the end of the tunnel was a bottle of champagne, as opposed to a mutilated body. For The Last of Sheila (1973) is a sort of John Dickson Carr or an Agatha Christie Death on the Nile whodunnit— up to a point, Lord Copper— set amongst the failing international jet-set on a yacht on the French Riviera.

Sheila’s (Yvonne Romain) in the film for about five seconds. Right at the beginning. During a party at their luxurious house in Bel-Air, she has an hysterical argument with her husband, James Clinton Greene (James Coburn), runs out into the road and gets mowed down (and killed) by an anonymous hit-and-run-drink-driver. Clint’s a multi-millionaire, a famous film producer. And just like Stephen Sondheim, Clinton’s a man obsessed with games. And games playing. I mean, like all the best people, he’s got that rather film-noirish board from Waddington’s Cluedo (1949) framed on his wall, alongside the Egon Schieles and reproduction Canalettos— alongside a bedroom on his yacht decked up in dodgy Louis XXXIV taste (“it’s like your Mother’s”)— in a notable set design from Bond Aficionado and Production Genius, Ken Adam, whose fabulous sets for Sleuth, in the Cluedobethan tradition, caused a sensation the previous year.

Games were very much part of the Seventies zeitgeist— partly, I suspect, because of the ‘connoisseur’ thing going on at the time. Games were hot. Take 1972’s Game of the Year— the Mastermind box featured a suave man with a beard (actually Bill Woodward, the owner of a chain of hairdressing salons) and a mysterious and sophisticated Chinese dollybird (actually Hong Kong’s Cecilia Fung, a computer science undergraduate at Leicester University). And backgammon was HUGE. Alongside tooled leather, balloon glasses of Napoleonic cognac, the Marseilles Tarot (very Tales of the Unexpected, that) and the chicken-wired libraries of chateaux in Lorraine— werewolf country. This was a time when people actually aspired to adult sophistication (fuelled by glamorous, backlit television ads and the recently invented credit card) as opposed to today’s Limited Edition Trainers à la Sotheby’s (oh, miaow!) and an Xbox. And the whodunnit concept is desperately Seventies (the Golden Age of the Board Game): regurgitated in Murder on the Orient Express (1974) and the amusing, if less effective pastiche, Murder by Death (1976) starring Peter Sellers as Charlie Chan. On British television, a bouffant Jon Pertwee hosted an ersatz gameshow, Whodunnit (1972-78), in which Patrick Mower, Anouska Hempel and Liza Goddard had to guess, yep— ‘whodunnit’— from a handful of out-of-work actors, committing dastardly murder in a five-minute sketch— actually, not unlike the amateur theatrical denouement at the end of Bruce Forsyth’s Generation Game (1971-77).

Anyway. Clint invites six suspects (i.e. potential parties to his wife’s manslaughter) on a delightful little cruise on his yacht, Sheila, along the Cote d’Azur. And little do they know what he’s got in store for them: they’re going to have to play his devious little game. They’re a motley crew, them suspects. Hollywood’s finest. Philip Dexter (James Mason) is a washed-out, if brainy, film director gone to seed, reduced to shooting Boffers Dog-o-Meet with Beef (rich in gravy) television commercials. He’s, well, more James Mason than ever, in his dark blue shirts— even if his hair’s a little bit greasy, grey and too long at the collar— and as all will be revealed in the film, he’s a man of unsavoury and disturbing inclination. And then there’s Alice Wood (Raquel Welch), a movie starlet who looks terrific in a bikini, the epitome of Seventies womanhood, who may have once, long ago, nicked a fur coat from a department store: apparently modelled (her looks that is, not the fur coat stuff) on Ann-Margret, or so at least poor Raquel was told by the producers, but actually, apparently, modelled on herself. Alas, James Mason failed to chime with Miss Welch, revealing indiscreetly to journalists that she was, I quote, “the rudest, most unprofessional actress I’ve ever had the displeasure of working with... or if I could, I would spank her from here to Aswan”. Ouch.

But let us continue… Alice is married to struggling talent agent Anthony Wood (Ian McShane). Ian's great. Forget the Lovejoy mullet; in the late Sixties and early Seventies, Mr. McShane was cast as a leading heart-throb: N. B. the gold medallion nestling on his hairy chest. And to add to the party, there's Tom Parkman (Richard Benjamin), a failing scriptwriter with expensive taste (“Louis Vuitton from writing Spaghetti Westerns") and his alcoholic wife, Lee (Joan Hackett), who’s probably the most genuine of the bunch, and secretary-turned-nymphomaniac-talent-agent Christine (Dyan Cannon) who’s almost as annoying as Michael Caine's wife in Ira Levin's Deathtrap (1982).

Richard Benjamin's another great. He's especially good in another one of my favourite films, Westworld (1973), as an insurance salesman turned fantasy gunslinger. Thinking about it, what is it about 1973? There must have been something in the water supply. Incidentally, please don't forget to remind me: we need to cover The Ballard of Tam-Lin (1970) at some point, starring an Aston Martin, a Rolls-Royce Corniche, an Alvis and a Jensen, and fifty-something Ava Gardner, with Ian McShane as her gigolo, all set to the hippy sound of Pentacle and also featuring— if you look hard enough— Bruce Robinson, Joanna Lumley, Richard Wattis and Jenny Hanley of Magpie fame. It's The Wicker Man (1973) meets Smashing Time (1967).

But I digress. The point is that all of 'em were present at Clint's cocktail party the night his wife gets killed, apart from Lee, who was at home in Santa Barbara, presumably getting pissed. So The Sheila Greene Memorial Gossip Game goes as follows: Clinton deals out a typed-up card to each suspect, the idea being that each of them has a grubby little secret from their past, a skeleton in their cupboard. And the name of the game is to match the card with the culprit. But the game, of course, is more elegant than that. Each suspect receives somebody else's card, inscribed with the other person’s past misdemeanour, some more serious than others. It's— er— slightly complicated, although as the pigeon brain of Yours Truly (once beaten at chess by a nine-year-old) managed to grasp what was going on in a second viewing, I am sure you'll get the hang of it. There's a touch of Columbo (1968-78) to all of this, albeit a louche, sophisticated and deliciously bitchy touch of Columbo, a wicked exposé of film industry types, helped along by lovely location work in the backstreets of Antibes and Nice. And Clint goes to town on the elaborate arrangements and settings, very Sondheim, that— including a Gothic, monastic set-up in the manner of The Castle of Otranto, with cowled abbots, stone cloisters, dripping wax, the hoots of owls and monkish plainsong emanating from hidden hi-fidelity equipment. It's a fiendishly clever plot, which keeps you guessing to the end.

Of course, by the standards of the 21st century, one of the suspect’s supposed little secrets now seems positively dated; and another might upset or even shock younger viewers— but again, it’s necessary, I think, to judge a film made in 1973 by the standards of 1973. To accept it— view it in context, and move on. It’s a different time and a different place. In any event, the critics loved The Last of Sheila (1973), with Roger Ebert, no less, describing it as a “devilishly complicated thriller of superior class… a very intelligent, witty, well-crafted mystery…” And it went on to win the 1974 Edgar Allan Poe Award for Best Motion Picture from the Mystery Writers of America.

Could Lindsay Anderson’s If…. (1968), Orson Welles’ F for Fake (1973) or The Last of Sheila be made today? No. I doubt it. Or, at least, I wouldn’t be surprised if a Last of Sheila remake (there’s talk, there’s talk…) might end up as a dumbed-down, anethetised, overly-polite and ultimately bland version of the original. But that’s one of the many, many things I like about late Sixties and early Seventies cinema. It’s not afraid to take risks. It’s Cinema for Grown Ups.

I watched The Last of Sheila (1973) on Amazon Prime Video Digital Download, which cost me £7.99 for keeps. A highly entertaining, and rollicking two hours of erudite fun. It’s also available, via various online platforms, in various DVD and Blu-ray editions, including newish Blu-ray releases— which look good. I’m currently saving up for a Blu-ray machine. Despite the considerable expense, it is something I could legitimately offset against my tax return.

Friday’s post is almost always for paid subscribers, but as a surprise August Bank Holiday bonus, I’ve decided to make today’s newsletter free. It gives the free subscribers a chance to see what they’re missing. Normal service will resume next weekend. And a huge thank you to those of you who have signed up as paid-subscribers so far. I really appreciate it. As you’ve probably gathered by now, I write two film recommendations every weekend. Friday morning’s post is for the crème-de-la crème, the paid subscribers (£5 a month or £50 a year). I tend to go for the slightly more unusual films on the Friday. The off-beat. Films you may not have seen or may not have heard of. Treat it like your very own Film Club. Sunday’s post, on the other hand, is for everybody, both ‘paid for’, and free subscribers. On Sunday mornings, I tend to go for the better known films, or films you may have seen long ago, but forgotten about. But it’s still pretty niche. Cinema for Grown Ups. I mean, if you’re patiently waiting for Star Wars (1978), Crocodile Dundee (1986) or the dreaded Titanic (1997), I’m afraid you may have to wait for a very long time indeed. Although, perversely, from the top of my head, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969), Jaws and The Deep (both released in 1977) might well be in the offing— especially as there’s much to say about the time and place these films were made.

So how are we doing? Since December 2023, we’ve now passed the 500 subscriber mark, and checking my stats, we’ve had over 7,000 views during the last 30 days. It's bloody hard work (7.00am sharp, a crawl to the computer, a cup of strong black coffee (I’ve almost finished my stale supply of Blue Mountain) and calluses on my fingers, but I enjoy it immensely. And it’s hard to believe, but today’s post is film no 75. And a paid subscription also gives you access to the entire WEEKEND FLICKS ARCHIVE, which, with the passing of time, is building up to be an invaluable resource.

And with my background in antiques, auctions and the art world, and a deep fascination with social history (I hesitate to use the word ‘historian’), my intention is to approach old films with a different mindset. In context; far removed from hyper-intellectual, film-school criticism— you know the stuff, full of long words you’re forced to look up in the dictionary and might win you a game of Scrabble. He said, with Sesquipedalian intent.

Great choice Luke. Knowing your thoughts on Daniel Craig I don’t know if you’ve seen the ‘Knives Out’ films - if you haven’t I certainly wouldn’t rush to do so. Craig’s wardrobe, despite being completely overdone, is of interest even though it looks like he stepped out the too glossy pages of an imaginary Anderson and Sheppard Haberdashery mail order catalogue. His quite absurd accent can be reminiscent of listening to Shelby Foote without the wisdom. Those elements aside both films have practically nothing to recommend them – except for fact that they’re very much modern failed attempts I think to capture the feel of this classic. They’re marginally successful in that too.

Makes me want to wear as Ascot every time I watch it.