The Picture of Dorian Gray (1945)

'I am jealous of everything whose beauty does not die...'

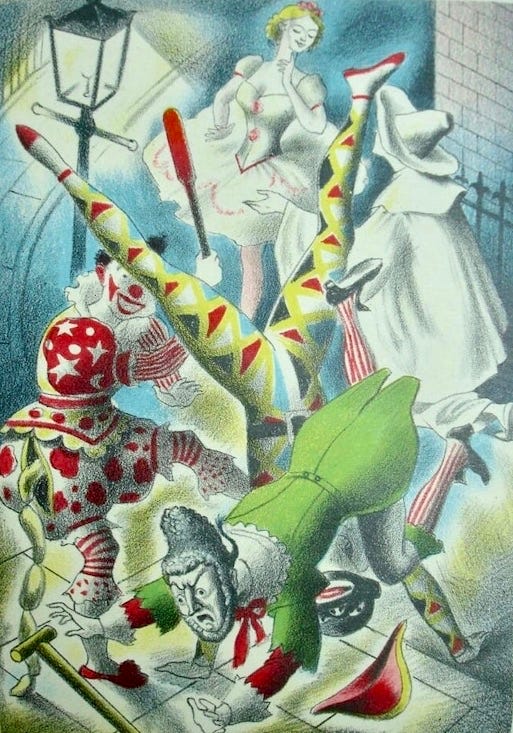

The late 1940s was a time of neo-Victorian revival, a vision rarely explored. Music hall graphics, Sacheverell Sitwell's rediscovery of Pollock's Toy Theatres, Sadler's Wells Ballet, The Saturday Book (John Hadfield's annual for grown-ups), the rich chromolithography of Clarke Hutton, and the women's fashions of 1947-9: roped shoulders and crushed velvet (Joan Chandler's dress in Hitchcock's Rope): all these things came together to create a romantic interpretation of the previous century— London by Gaslight if you will, as seen in the cinema of the time: Gaslight (1944), The Magic Box (1951), and Footsteps in the Fog (1955).

It's not surprising when you think about it. Creatives tend to revisit the era of their birth: writers, filmmakers, influential advertising and marketing types. The same thing happens in the 90s with the retro revival (Austin Powers) or with the 70s obsession with the American Depression: Bonnie and Clyde (1967), The Waltons (1972), The Sting (1973), and Bugsy Malone (1976).

Albert Lewin’s The Picture of Dorian Gray (1945) has the Neo-Victorian in spades—adding a further dimension, or layer in time— a triumph of monochrome Gothic film noir. Lewin is an interesting director— a cultured, maverick aesthete hidden within Hollywood’s studio system: ex-Harvard (a Masters in English Literature), a Columbia PhD candidate, an art collector and friend of Jean Renoir, Man Ray and Max Ernst. Lewin’s films are both elegant and exotic, often with a literary bent: The Moon and Sixpence (1942), based on Somerset Maugham’s novel of 1919; The Private Affairs of Bel-Ami (1947), based on de Maupassant’s classic, Bel Ami; the surrealist (Pandora and the Flying Dutchman (1951), (which we covered in a previous post); and The Living Idol (1957)— in which ‘an archaeologist believes that a Mexican woman is a reincarnation of an Aztec princess’.

Like Pandora—and there are notable similarities between the two films— Dorian Gray has a weird, dream-like quality. It's shot in a film noirish black and white, apart from brief technicolor inserts when the hideous portrait is finally unveiled—oh horror! Based on Oscar Wilde's tale of the supernatural, Hurd Hatfield stars as a Chopin playing Dorian Gray, the decadent aesthete who, in a Faustian pact, swaps his youthful good looks for a mouldering portrait hidden upstairs in his childhood nursery.

Wilde's novel was published in 1891— and is very much a product of its time. The stark contrast between the prosperity of the West End and the degradation and poverty of the East End became an obsession, both in clubland (The Athenaeum) and in the Late Victorian press, explaining— to some extent— the panic, furore and press frenzy surrounding the Whitechapel murders of 1888-1891, mirrored, two years earlier, in Robert Louis Stevenson's Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886). This idea of the double identity, the top-hatted toff living it down in the slums was seen by writers and observers of the time as Victorian upper and middle-class hypocrisy; something rotten in the heart of Empire. You find this too, I think, in Manet's Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882)— surely one of the saddest paintings ever painted? And this 'double identity' also represents Wilde's homosexuality, although the more obvious undercurrents are toned down in the film.

Lewin's 'fastidious evocation of fin-de-siècle aestheticism' is superb. It has that certain je ne sais quoi. Oscar Wilde lived in Tite Street— and I’m thinking, from the top of my head: a fog-bound Cheyne Walk (Pont Street Dutch), blue and white china, Japanism, Morris & Co. stuffs, bodies fished from the river (The Thames Torso Mysteries of 1887-1889), the rattle of the hansom cab— the London of Rossetti, the Grosvenor Gallery and James Abbott McNeill Whistler. It's no coincidence that Wilde's wife, Constance, was a founding member of the secret occult society, The Golden Dawn. And Lewin, typically, includes numerous high-brow references in an otherwise middle-brow Hollywood picture, which might, perhaps, have been lost on an audience in the American Midwest: Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur (the Aubrey Beardsley edition of 1893), Baudelaire's Les Fleurs du Mal, the kitsch appeal of The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyám:

I sent my soul through the invisible, some letter of that after-life to spell:

And by my soul returned to me,

And answered, ‘I myself am Heaven and Hell’.

The set design is magnificent, from the lily-scented brick of a garden in Cheyne Walk to Dorian's rather grand Mayfair house (as imagined by Hollywood) contrasted with the derelict music-hall-cum tavern in the desolate wastelands of the East End docklands. As you might expect in a Lewin picture, the film is punctuated throughout with numerous antiques and objets d'art. Wilde's Devil was replaced, for censorship reasons, with an Egyptian statuette of the Cat god, Bastet, and Lewin has Dorian pouring over his rare coin collection, in a similar vein to Geoffrey Fielding, the avuncular archaeologist in Pandora and the Flying Dutchman. And as with Man Ray's contributions to Pandora, The Picture of Dorian Gray includes the work of American Realist artist, Ivan Albright. The second 'hideous' portrait— finally revealed in all its glorious, avant-garde Technicolor, caused, apparently, a sensation when it was first exhibited at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1945. The first portrait of the 'pre-corruption' Dorian was painted by Henrique Medina (1901-1988) and sold at the MGM auction in 1970, subsequently resurfacing at Christie's in 2015, where it fetched $149,000 against a cautious— if sensible— estimate of $5000-8000.

.

What else? Angela Lansbury makes for a delightful— if vulnerable Sybil Vane, the Cockney Sparra'. And George Sanders is splendid, as ever, as the urbane cynic, Lord Henry Wotton. The Donna Reed character, Gladys (now there's a 1930s name if ever there was), is not found in the original book and makes her first appearance as a cutey-pie American child at the beginning of the film. Hatfield, I think, is brilliantly cast, despite the deviation from Wilde's original Adonis ('frank blue eyes…. crisp gold hair'). Hurd ('a keen collector of art and antiques... [he] never married'), with his effete, clean-cut, chiselled good looks, is deadpan, as if almost lobotomised— adding to the weird, dream-like feel of the film. But then there's more than meets the eye in an Albert Lewin picture. Criticised at the time for his ‘literary and artistic pretensions’, he is, surely, one of Hollywood’s most interesting directors.

I watched The Picture of Dorian Gray (1945) via Amazon Prime digital download. It’s also available on DVD and Blu-ray.

You've just been reading a post for both 'paid for' and 'free' subscribers. To view the other films we've covered so far, please go to the Luke Honey WEEKEND FLICKS. archive. 'Paid for' subscribers get two weekend film recommendations, access to the entire archive and the ability to comment. By the end of the year, there should be over 100 film recommendations.

I’ll be back on Friday. In the meantime, thank you for reading and I hope you have a relaxing weekend…

Hey Luke, this was great fun to read. And insightful. I’m trying to remember when I first saw the film…it must have been on TV when I was about 16/17…was it twinned with The Trials of Oscar Wilde (Yvonne Mitchell as Constance…very touching…) in a kind of wild Wilde-fest? Or I could be merging the two?

I dig your points re Hurd Hadfield…they something of the same torpidity that Keane Reeves can sometimes do so interestingly.

I thoroughly enjoyed reading every word Luke, a tremendous insight and Oscar certainly gave us much to think about. I loved this film and I spotted a little mention of one of my rainy afternoon favourites... Footsteps in the Fog !