Even during the short periods when their lives were stationary, which had been few enough since their marriage, twelve years ago, he had only to see a map to begin studying it passionately, and then, often as not, he would begin to plan some new, impossible trip which sometimes eventually became a reality. He did not think of himself as a tourist; he was a traveller.

Paul Bowles, The Sheltering Sky, John Lehmann [1949].

The Hotel Continental stands high on a bluff, overlooking Tangier’s busy, and somewhat industrial port, a sanctuary from the squalor of the streets (or, at least, how it was in the early 90s) like the bow of a fine old ship, shabby but proud, and facing the Straits: directly ahead, the Spanish port of Tarifa (with its huge statue of Christ, looking out to sea), and to the right, and up a bit, the British overseas territory of Gibraltar. It’s a fascinating part of the world, where the European toe dips into the deep waters of Africa, where only eighteen nautical miles of Mediterranean separates Catholic Christendom from the Islamic World, a cultural triangle — Spanish, British, and Moroccan — where civilisations meet, sometimes clash and often gel. The Continental was built in 1870, before the years of the shady International Zone, when Tangier was a fashionable winter retreat for Bohemians, artists and the British upper class, and in the years before the First World War, Sir John Lavery, John Singer Sargent and Henri Matisse came to Tangier, inspired by the light.

I’ve stayed there twice, at the Hotel Continental, in the very early 90s, the first time by myself, a stepping stone for a two-week tour of the Imperial cities of Marrakesh, Meknes and Fez, and then again, with my Canadian girlfriend (fellow auction specialist and later, failed fiancée). The elegant steamers of the Victorians, where English ladies and their parasols once embarked, replaced by the rusted ferry from Gibraltar. And the modern world moves on, leaving the Continental, once grand, to its memories; Winston Churchill’s fading signature in brown ink in the visitor’s book and an antique mahogany longcase clock juxtaposed against the cracked Islamic tiles of the hotel lobby. According to The World of Interiors, which in December 2024, photographed the hotel for posterity, the Continental is threatened, like so many other historic institutions, with closure. These I have loved.

I mention this in passing, as The Hotel Continental, alongside The El Minzah hotel and many other splendid locations, stars briefly in Bernardo Bertolucci’s adaptation of Paul Bowles’ first novel, The Sheltering Sky, published by John Lehmann in 1949 and which I read again for this post. It’s a fabulous book. And its existentialist themes may well have shocked readers at the time: the individual’s place in a vast, indifferent universe; brutal, dark eroticism; alienation, despair and psychological disintegration leading to near-insanity. How the destructive nature of unchecked desires, how a lack of discipline and self-control, can lead to degeneration — and danger.

The Sheltering Sky is set in French Algeria in the late 1940s, just after the Second World War. Porter and Kit Moresby (John Malkovich and Debra Winger) are restless, well-heeled American sophisticates. Supposed Bohemians from Manhattan, the spiritual home of the Dry Martini. In the film, there's a more obvious parallel with Paul Bowles and his wife, Jane Auer. Port, like Bowles, is a composer, and Debra Winger's rather Eighties quiff (silky blonde in the book) is, I suspect, a direct and deliberate reference to Jane's dark-haired mop. And ignoring that wise maxim, 'two's a company and three's a crowd', they're joined by George Tunner (Campbell Scott), a clean-cut, Ivy League American — bland, handsome and stupid in 'a late Paramount way'. We're in Talented Mr Ripley territory here, without the murder: rich, transient Americans abroad; and despite their complaints about the Algerian Pernod, ce n'est pas vrai Pernod, they're 'travellers, not tourists'. Despite the vintage luggage wank-fest: the Louis Vuitton steamer trunks, the pith helmets, the hat boxes, wooden tennis rackets, the canvas and pig-skin — "you have some nice labels on your bags"; Mumm Cordon Rouge in the First Class railway carriage, as opposed to a rancid fowl in the Fourth.

I’m a fan of John Malkovich, who so often plays his cynical self, or at least, seemingly the same character or type, and I’m immediately thinking The Object of Beauty (1991) and Ripley’s Game (2002). He’s well cast as the selfish Port. Both Port and Kit are incredibly into themselves. And that’s one of the remarkable things about Bowles’ novel. How, in spare, chiselled prose, Bowles captures the way people think in real life: complicated, superstitious, irrational and often neurotic. But, as we discovered with John Huston’s Under the Volcano (1984), sometimes a sophisticated novel is almost impossible to replicate on the Silver Screen. They are two very different mediums. This was one of the complaints Bowles had about the film, “the less said about the film, the better” — a little bit harsh, perhaps, as Mark Peploe’s script sticks faithfully to the novel throughout.

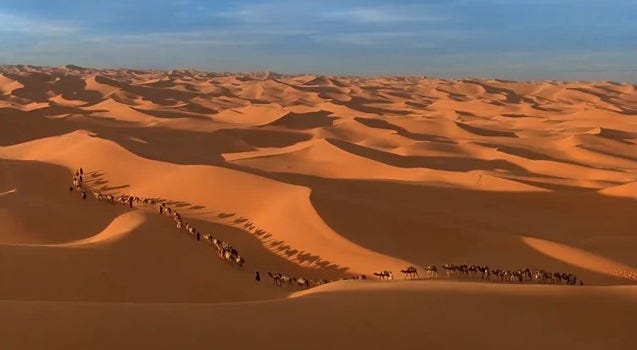

And as Port, Kit and Tunner journey through North Africa and leave Western values behind, there is a growing sense of isolation, accentuated by stunning location work: the seedy cafés (Charles Trenet on the gramophone), fly-infested pensiones, the hell-hole of a French Foreign Legion fort, the alien beauty of Ait Benhaddou. Cue the monstrous Lyles: the anti-semitic travel writer, Mrs Lyle (Jill Bennett) and her ghastly son, the creepy Eric (Timothy Spall) — in the book, there’s a hint of incest — who turn up in a dusty white Mercedes-Benz, and shadow the rest as they journey across the desert, which reminds me of how, when you one is travelling in Morocco, or wherever, so often, strangers (with whom you have absolutely nothing in common with) flock together. Bennett and Spall steal the show. Spall is (or was) especially good at this sort of thing. Eric, thinking about it, is not dissimilar to Dr. Polidori, Lord Byron’s sycophant, in Ken Russell’s Gothic (1986).

Despite Vittorio Storaro’s lush cinematography, or maybe because of Storaro’s lush and stunning cinematography, the critics were not especially convinced by The Sheltering Sky (1990), with Roger Ebert giving the film only two stars and “left with the impression of my fingers closing on air”. Paul Bowles (who appears in the film as the narrator — he’s the distinguished old boy in the café) criticised the emphasis on the visuals — like an exotic travelogue, or an expensive adventure holiday brochure — at the expense of all the stuff about psychological disintegration. Certainly, having finished the book yesterday, the last quarter of the novel, which degenerates into a haze of masochistic (and at times, erotic) sexual exploitation, is very much watered down, in the film, for an audience of the 1990s, and the brutality and indifference of the Tuareg warrior and camel driver, Belqassim, is replaced by smiles and gentle eyes.

So there you go. The Sheltering Sky (1990). Perhaps the best way forward is to read the novel and make up your own mind. Personally, despite the softer ending, I like the film very much indeed, and it’s a notable addition to the WEEKEND FLICKS. archive, which now harbours some 158 films. I watched it on my own DVD, but it’s also available on Amazon Prime Video, and I suspect other video platforms.

And by now you should know how WEEKEND FLICKS. Cinema for Grown Ups works. Friday’s post is for the Paid Subscribers (£5 a month or £50 a year). An elite coterie of discriminating cinephiles. Paid subscribers also get access to the entire archive, which goes all the way back to when we started, in December 2023. And Sunday’s post is free, and open to all. Two film recommendations to get your teeth into over the weekend. Time to sit back, relax, mix a cocktail — and watch an old film. A Marrakech Mule for this one, perhaps more for the name, than the actual concoction — which sounds revolting. But then there’s always Mint Tea.

,

We miss you, Sakamoto! (bowing in reverence.)

I remember seeing this in the cinema and being stunned by the beauty of Winger, Malkovich and the scenery but otherwise left mystified. Nothing but contempt for these moneyed, pointless people, as I was working 18 hour days in the City at the time. The same attitude ruined The English Patient for me, as by then I had added a baby to the mix. I sat watching Fiennes and Scott Thomas being beautiful and tormented by love, and muttering 'what you two need is a trip round Sainsbury's on a Saturday morning with a toddler. That's where all this takes you'.