Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines (1965)

Or how I flew from London to Paris in 25 hours 11 minutes...

I spent a languid afternoon, yesterday, watching Ken Annakin’s Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines (1965) — and I’m so glad that I did, as it’s a splendid romp of a film, which, despite the Mid-Sixties whimsy and Keystone Cops slapstick, is actually, at the same time, a loving historical homage to the early days of flying. And it’s beautifully made, too, with luscious, saturated cinematography from Christopher Challis.

The film is set in 1910. Press baron Lord Rawnsley (Robert Morley), proprietor of The Daily Post, decides to hold an international London to Paris air race, with a prize of £10,000 to the winner. This was an awful lot of cash in 1910, according to the Bank of England inflation calculator, worth over £1m in today’s money. And it’s worth noting that for the London to Manchester air race of 1910, sponsored by The Daily Mail, the prize was the same amount, yet poor Louis Blériot only received a mere £1,000 for crossing the channel in 1909 — a remarkable feat at the time. And so the stage is set for a magnificent assemblage of rickety flying machines, like something straight out of W. Heath Robinson.

If you’re into this sort of thing — early aviation and veteran cars, pre-First World War militaria and Edwardian fashion, you’re in for a field day. As we’ve discussed in earlier posts, early mechanica, during the 1960s, was dead trendy — especially when it came to graphics. Images of veteran Rolls-Royces, Blériot monoplanes, hot air balloons — think Fornasetti — and other aspects of (late) Victoriana and Edwardiana (i.e. Penny Farthings) — think The Prisoner — were anywhere and everywhere: on mugs, ashtrays, calendars, dinner services, restaurant menus and, of course, prints. In The King’s Road, gentleman publisher, Hugh Evelyn, purveyor of prints to the set designers of Swinging London, produced luxury folios (for framing) of historical uniforms, ships, zeppelins, carriages, trains, ‘planes and veteran cars.

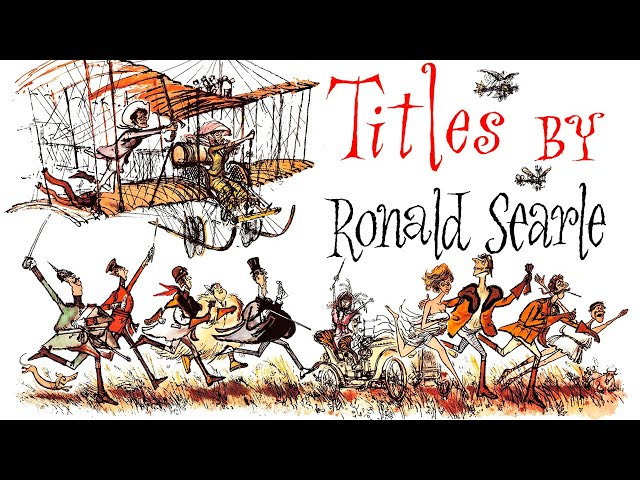

And there’s one illustrator (or perhaps two, if you include Rowland Emett) who sums this all up: Ronald Searle — who, famously, designed the titles for Those Magnificent Men, which is set to Ron Goodwin’s catchy little number: the sensation of 1965 and No. 5 in the Hit Parade. (“Well, better than The Smurfs or Grandad”, says Venetia.)

Those magnificent men in their flying machines

They go up, Tiddley up, up

They go down, Tiddley down, down

They enchant all the ladies and steal the scenes

With their up, Tiddley up, up

And their down, Tiddley down, down

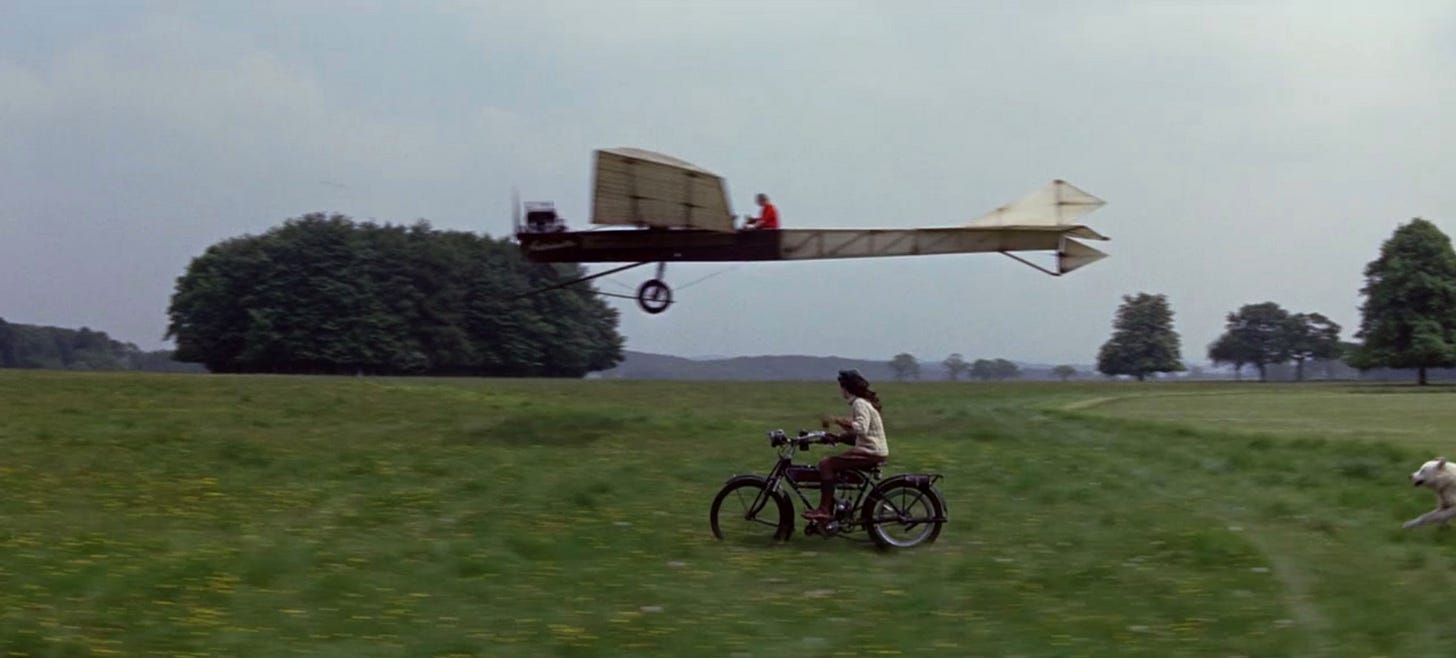

And the more I research Those Magnificent Men, the more remarkable I find it. No phoney, puerile, kidult CGI for this one. The flying machines are proper, real-life, grown-up flying replicas, built at a cost of £5,000 each, including an Avro Triplane IV, a Bristol Boxkite, an Eardley Billing Tractor biplane, and a Blackburn monoplane.

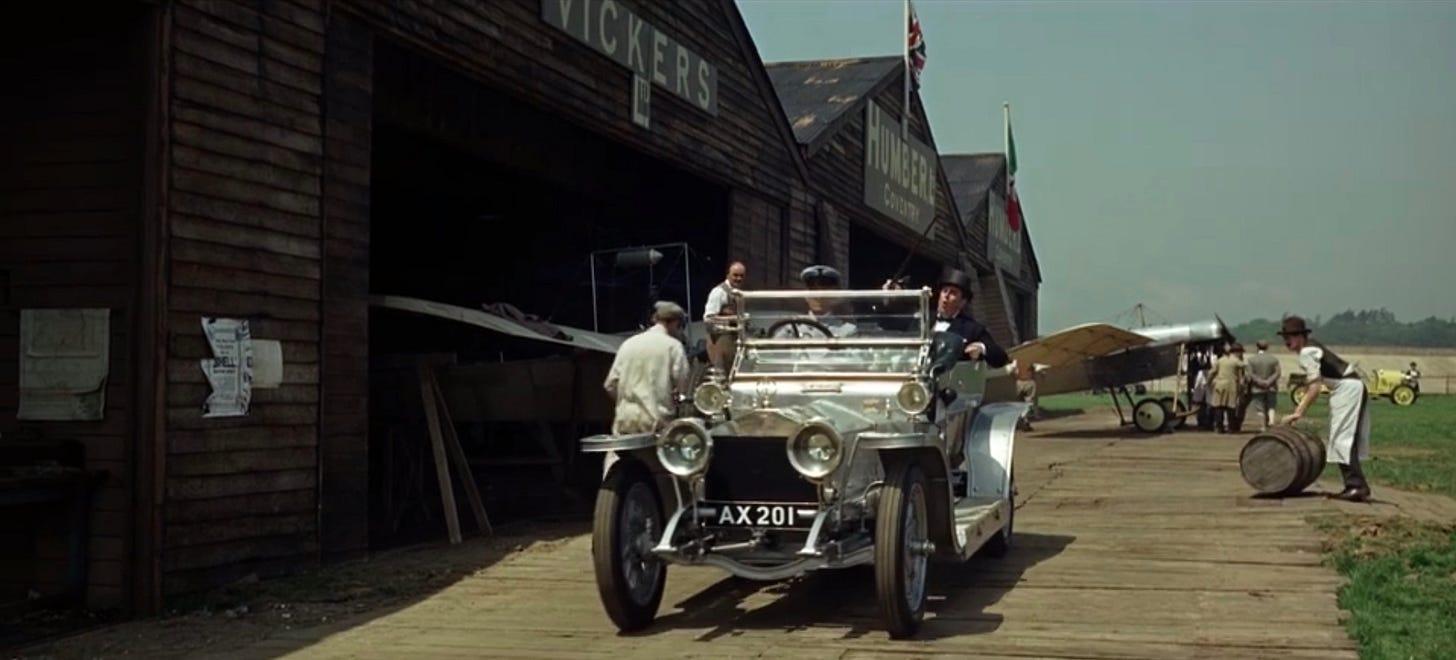

Brooklands Motor Course was constructed by Hugh Locke King in Weybridge, Surrey, in 1907, and by 1910, had also become the home of British aviation. Brooklands became a fashionable place to see and be seen; with the ‘fast’ young ladies begging the handsome and dashing pilots to take them up in their rickety and dangerous aeroplanes. Fans of K. M. Peyton’s delightful novel, Flambards (1967), will know all about it. So in Those Magnificent Men, all this is recreated in a remarkable set at Booker Aerodrome, to be found in the chalky Chiltern uplands, near High Wycombe in Buckinghamshire — also used as the airfield in Aces High (1976). The hangers, sheds, white picket fences, banked race track and clubhouse are lovingly recreated — it’s the most wonderful evocation — and there’s a splendid fleet of original veteran cars (including a 1910 Dennis Fire Engine and a Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost, subsequently valued at $50 million). Plus an adjacent sewage farm (just like the original Brooklands), which gives rise to a series of amusing dunkings. Terry-Thomas in la merde.

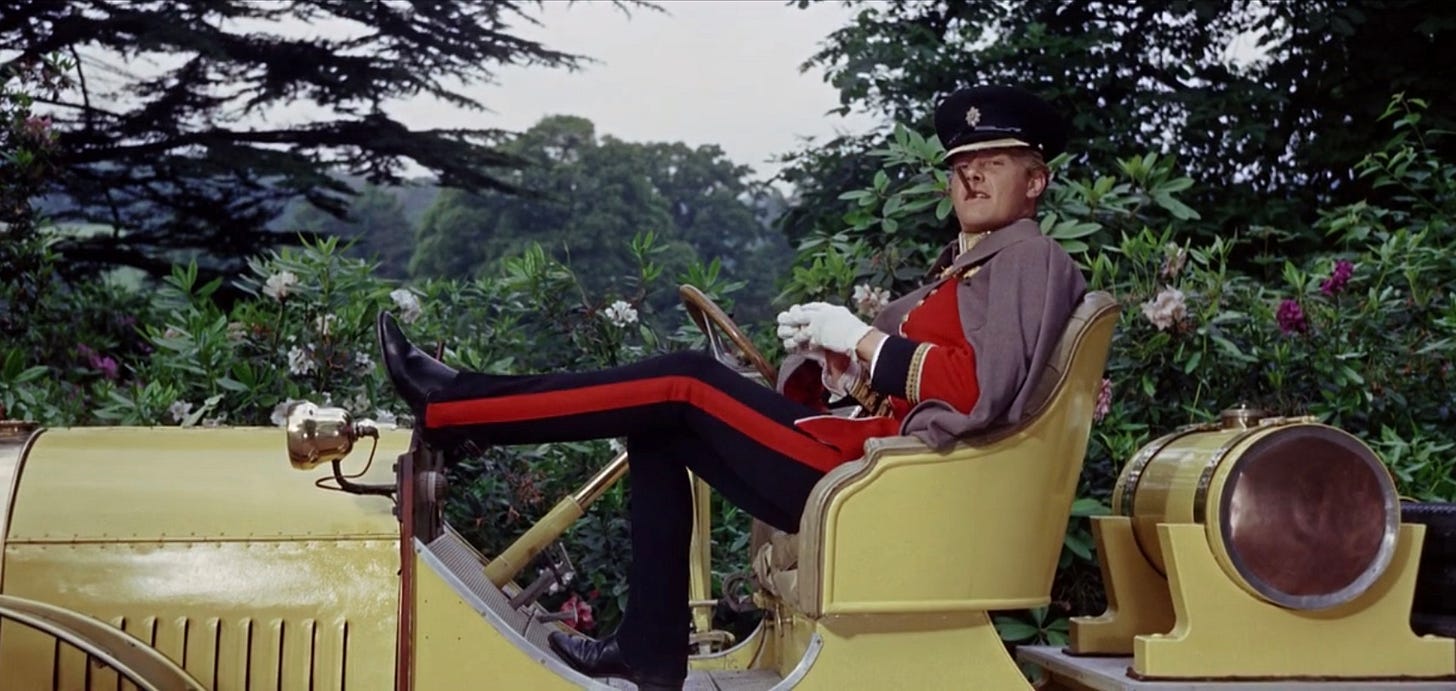

Visually, Those Magnificent Men looks fabulous — I cannot stress this enough — with luscious, saturated cinematography shot in crisp, high-definition, wide-screen 65mm Todd-AO. And actor-wise, it’s a cracking parade of fashionable, mid-Sixties talent: Elegant James Fox, more or less fresh from his superb performance in Joseph Losey’s The Servant (1963), in the same role, more or less — in Old Harrovian tie and the double-buttoned scarlet tunic of his old regiment, The Coldstream Guards. Fox’s on-off girlfriend, Sarah Miles (Fox’s co-star in The Servant), as Lord Rawnsley’s feisty Suffragette daughter (possibly miscast?), Gert Fröbe as Colonel Manfred von Holstein, Robert Morley, Stuart Whitman, Jean-Pierre Cassel, Willie Rushton, Jeremy Lloyd, Benny Hill, Eric Sykes, Gordon Jackson, Dame Flora Robson, Tony Hancock and James Robinson Justice. Yep, they’re all in it, and, last and certainly not least, there’s Terry-Thomas, an old friend of WEEKEND FLICKS., as dastardly cad Sir Percy Ware-Armitage.

Of course, all the international competitors — the British, French, Germans, Americans, Italians, and Japanese, conform to national stereotypes, representing the Great Powers at the time of the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914. Not that this concerns me in the least, hey! After all, it’s 1965 ain’t it? — but, y’know, the British are patronised as stuffy (or perfidious) chinless wonders, the French are sex-crazed womanisers, the happy-go-lucky, unsophisticated American rednecks are gung-ho cowboys; the Germans are a troupe of robotic automatons led by a bull-necked colonel in monocle and pickelhaube, the aristocratic Italians, good Catholics that they are, breed like rabbits, and the Oxford-educated, inscrutable Japanese speak English with decidedly pukka accents.

And the film is framed with two lovely little sequences on the history of aviation. The introduction is narrated by that splendid champion of the Tsarist beard, James Robinson Justice, an amusing little montage of the eccentric early days of flight, based on silent footage in sepia, with aeronautical lunatics strapping themselves to feathered wings and leaping off cliffs; and the final moments (and I’m not giving too much away here) become a sort of homage to Anthony Asquith’s The V. I. P. S (1963), with a frustrated Liz Taylor and Richard Burton trapped in a fog-bound London Airport.

So there you go. Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines (1965). D’you know, thinking about it, I adore this film. It is truly magnificent. And if there was ever a contender for ‘Sunday Afternoon Tea-Time Film of the Year 1965’ — this is going to be it. There’s an intermission too, always a good thing, which means time for cute little tubs of vanilla ice cream and dinky wooden spoons found beneath the lid, which leave a furry taste on the tongue. If you’re struck down with the blues and in need of cheering up, as sometimes we all are, I would prescribe Those Magnificent Men as a cure. The Widow Clicquot for this one.

I watched Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines (1965) on Amazon Prime Video and it’s also available on DVD and Blu-ray. For rare book aficionados, Ronald Searle’s illustrated edition (Dennis Dobson, 1965) based on the film, floats my boat. I had a quick look on the net, and prices seem reasonable — altho’ for some unexplained reason, most copies seem to be found in America.

Checking the archive, I’m reminded that the very first post on WEEKEND FLICKS. Cinema for Grown Ups dates from December 2023. The great idea (which, like Archimedes, came to me in the bath) was to create a feel-good film newsletter for subscribers to enjoy, and hopefully use, over the weekend — inspired by the old LWT ident — when, at Friday teatime, earnest Thames Television handed over to the racier London Weekend. So here’s a quick word about the paid subscription, which costs £5 a month or £50 a year. Paid subscribers receive their own special post on Friday mornings, special additional posts (when I can, and please bear with me on that), and access to the entire archive — now running at 154 films. The Sunday morning posts are free and can be read by anybody and everybody. I’ll be back on Friday with another recommendation. Until then. Au Revoir.

In 1966, the night before the World Cup final, my aunty Sylvia and her friend, Coral took me to Hendon Odeon to see Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines. It was the days when you had old guys in elaborate, gold braided uniforms stood outside. Anyway, there we were, waiting in line to enter the cinema when, in twos and threes, the entire England squad join the line for the box office.

We get inside, in the dress circle, and I’m sat two rows directly behind Jack Charlton, who is sat with Bobby Moore and (I think) Martin Peters. Over to my right, across the aisle, and down a few rows, is Nobby Stiles — the first and only time I ever saw him wearing glasses, sat with Alan Ball and (I think) Roger Hunt.

Anyway, as the lights go down and we settle down to watch Pathé News and the adverts the cinema manager makes a big mistake by announcing the fact that the squad are in the cinema, and requesting that we all leave them alone to enjoy the film. Straightaway people are looking every which way trying to spot them, lines of autograph hunters are queueing in the aisles. I was so excited I thought I was going to piss myself — so off I went to the Gents. As I was going down the stairs to the WC Gordon Banks was jogging up the stairs — he was late. He patted me on the head as he passed. I go back to my seat and my aunty and her companion are going through their handbags looking for something I could ask the players to sign. All through the first part of the film — before the intermission — my view of the screen was blocked by this big fella. I had some Thunderbirds bubble gum cards in my pocket and I thought I could ask Jack and Bobby Moore and Martin Peters for their autograph during the first intermission. I bottled it.

I go back to school after the summer holidays and, of course, tell all me mates, “Never guess what…”

Nobody, absolutely nobody, believed me. Over the years, before the internet, I began to doubt that it had ever happened myself.

Fast forward to 1996 — thirty years later, Newcastle Irish Festival, and I’ve been invited to the first night of a Sean O’Casey play by an Irish theatre company at Northern Stage. I was with a very good friend, a die-hard Middlesbrough fan. Anyway, just before the first interval we went down to the bar. And, yep, you guessed, Jack Charlton is sat at the bar on his own, having a pint and a fag. My mate wanted to go and remonstrate with him about, as he saw it, leaving Boro in the lurch. Anyway, we chatted with him — he regaled us with loads of good yarns — and then I told him ,“The last time I saw you in person was the night before the World Cup final…Hendon Odeon, Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines…” He smiled. Then I told him, “I never did your autograph.” And he laughed.

We asked how it was he was in the theatre. He told us that a couple of weeks’ or so prior he was having a lunchtime drink in a local pub when a group of Irish actors walked in and recognised him. They introduced him to a Guinness rep, who were part sponsoring the show, and he gets the gig of pouring Black Velvets at the first night party. He tells us to come along. So we did. The space was rammed with the cast and local nabobs, dignitaries and the usual suspects. And, there’s Jack, dutifully pouring Black Velvets. He sees us and calls us up to the bar. He pours us two Black Velvets, and, as they settle he says to me, “I never caught your name the first time we met. Here,” and he passed me a scrap of paper and a biro. “Write it for me.” Jack Charlton asked for my autograph. So I gave it him. You can imagine the looks and comments of some people attending — “Whose he? Jack Charlton just asked for his autograph.”

Top bloke — a real gentleman — with a warm, if wicked, sense of humour. R.I.P.

Thanks for this. First film I ever saw in a cinema - aged 5. I will still watch anything with TT in now. And read anything illustrated by Ronald Searle...