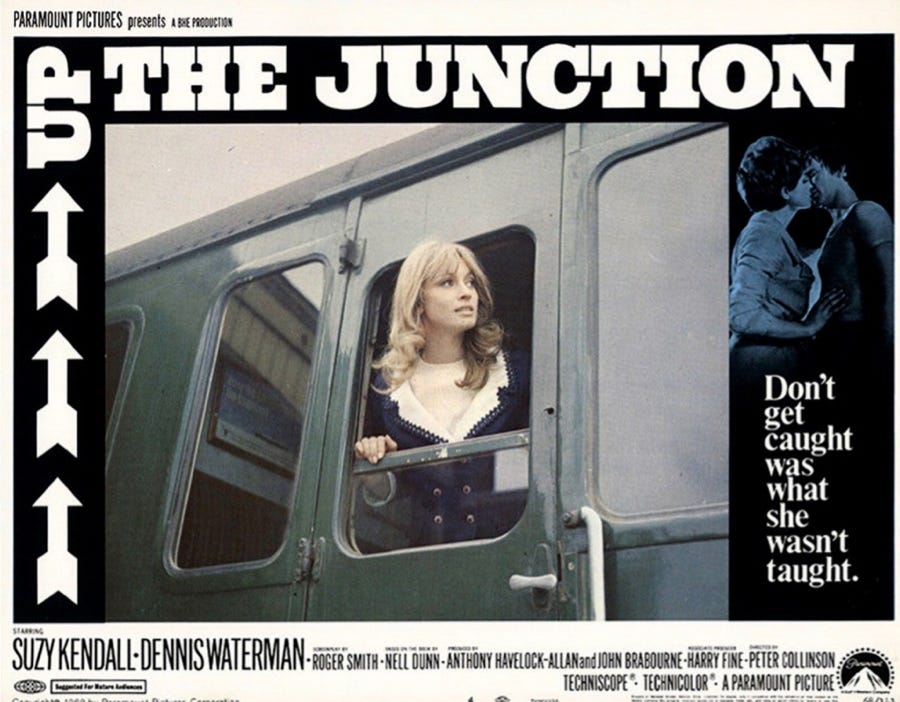

It’s back to London on Luke Honey’s WEEKEND FLICKS. Cinema for Grown Ups. We’ve got two key London films for you. First up is Peter Collinson’s Up the Junction (1968), starring the divine Suzy Kendall as a bored Chelsea It-Girl and Dennis Waterman as a bit of rough.

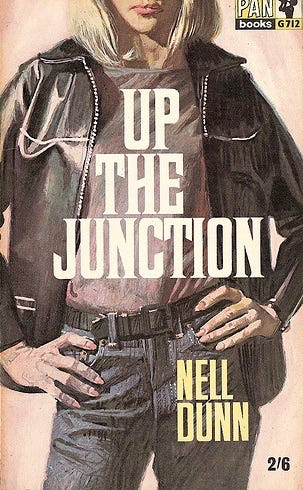

Posh Polly (Suzy Kendall) decides to slum it darn sarf and discover ‘real’ life in the mean streets of Battersea. The film’s based on Ken Loach’s gritty television play for the BBC (1965), the height of kitchen sink, in turn based on Nell Dunn’s collection of autobiographical short stories— when, I quote:

In 1957, after her marriage... they gave up their smart home in Chelsea and went to live in unfashionable Battersea where they joined and observed the lower strata of society...

So Polly crosses the river, gets a job at the Macrindle’s confectionary factory, makes friends with Sylvie (Maureen Lipman) and Rube (Adrienne Posta), finds a grotty flat near Clapham Junction and ends up with a kitten. And there’s abortion and a tragedy. And motorbikes and mopeds, and a Knees Up Mother Brown in an old boozer underneath the railway viaduct (with nicotine-stained ceilings and green glazed ceramic tiles) and market traders, bomb sites, jellied eels and junk shops. And a nice working class lad, Pete (Dennis Waterman), who drives a van and Polly fancies.

Maybe Chelsea was boring in 1957, but by 1968, the place was swinging. At least in The King’s Road. So why abandon ‘happening’ Chelsea for Battersea? Time for a head examination. I mean, if Polly had played her cards right and stayed in Chelsea, she might have been a metaphorical guest at the Blow-Up (1966) party, shot in Christopher Gibbs’ flat in Cheyne Walk. And that’s one of the problems I have with the film. It’s a flaw.

Incidentally, Polly's house, a Regency number in white stucco, smooth green lawn and chauffeur-driven Rolls parked on a crunchy gravel drive, was filmed at Forbes House in Ham— one might struggle to find such a house in Chelsea. And in any event, by today's standards, Chelsea was more of a Bohemian mixed bag in 1968 (especially as you walked down the King's Road towards World's End); with a shabby gentility, plus a decidedly working-class area around the Chelsea power station: hardly Belgravia or Mayfair, even if the social divide across the river was noticeably starker. This was before the creep of gentrification in the 1980s, when the Sloane Rangers began to buy up the Victorian semis in Fulham (SW6) and Battersea (SW8 & 11)— pushed out of their natural habitat— Chelsea (SW3), Kensington (W8) and South Kensington (SW7)— by rising house prices. No. Polly might have lived in Knightsbridge or Belgravia. But from a cinematic point of view, the great social divide of the River Thames, between the rich to the north and the poor to the south makes a statement. A massive generalisation, of course. But as with so many generalisations, there's some truth in it.

Dennis Waterman puts in a terrific performance. As an actor, he's entirely natural. And just like Polly, Pete wants to escape his background and find 'real life', whatever that means. But there's a major difference. Polly can bugger off back to Mummy and Daddy when things get tough. Pete can't. He's trapped in poverty, in a dead-end job. There's a touching moment in the film when Pete takes Polly back to the ruins of his family terrace, presumably being demolished to make way for a council tower in concrete, and his magazine pin-ups are still there on the flowery paper on the wall of his old bedroom— an Aston Martin and a castle in Ireland. Looking ahead, Pete's a proto-yuppy, dare I say it, even aspirational Thatcherite: he's clever, he's ambitious, and quite understandably, he aspires to the finer things in life, all the trappings Polly rejects.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Luke Honey's WEEKEND FLICKS. to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.