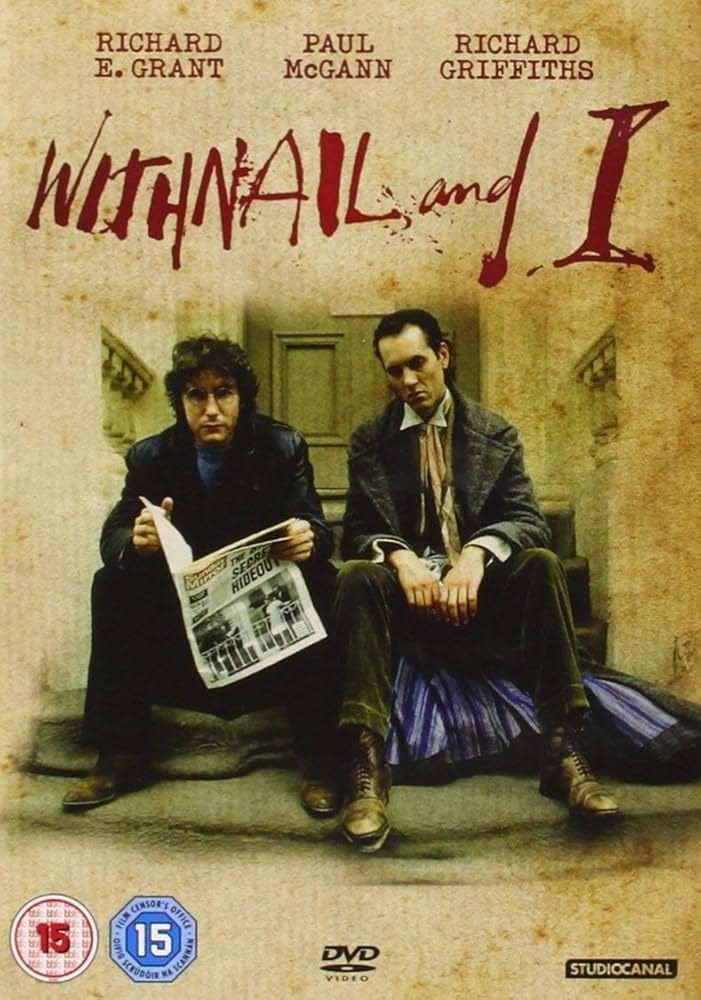

Withnail & I (1987)

"We want the finest wines available to humanity. And we want them here, and we want them now!"

In the Spring of 1987, my wife attended a low-budget British film premiere. The after-party took place in a dank, dark, sweaty basement somewhere in Soho. There was a lot to drink. The film was Withnail & I, which, although it made a small profit at the box office, more or less sunk without a trace. Today, thanks to Bruce Robinson’s brilliant script and championed by the lad’s mag, Loaded, Withnail & I has become an adored cult classic, especially amongst students and other layabouts, with obsessive fans re-enacting the drinking scenes (vinegar a substitute for lighter fuel), yelling at schoolgirls from car windows, reciting lines and stalking Sleddale Hall, Uncle Monty’s cottage in the Lake District— although, apparently, the bedroom scene (where Uncle Monty tries to seduce Paul McGann) was filmed at good old Stockers Farm, near Watford, the bucolic location for The Adventures of Black Beauty (1972-74) and Ken Russell’s wunderwerk, The Lair of the White Worm (1988). And if Venetia had her own modest Withnail moment (a fact I’m secretly impressed with, not, of course, that I would admit that to her), then so did I— or rather, I had my own Uncle Monty moment, or to be more accurate, a moment in Uncle Monty’s house.

During the school holidays (this was the early 1980s), my best friend— now the underground record producer and distinguished street photographer Miles Morgan— encountered the distinguished textile aesthete, Professor Bernard Nevill, riffling through a tatty, dog-eared stack of Victorian portrait photography in an antiquarian bookshop in the Charing Cross Road. "Don’t I know you, Dear Boy?" transmogrified into an invitation to West House, the Prof’s glorious Arts & Crafts pile in Glebe Place, just off the King's Road, the location, as you know, for Uncle Monty's glorious Victorian extravaganza— an invitation to tea and crumpets. From memory (and it's a good one), Miles turned down the invitation, but then, a few weeks later, on a brisk Saturday morning, we knocked on Professor Nevill's iron-studded oak front door. Oh, the arrogance of youth! Poor Bernard appeared in a flamboyant silk dressing gown (Liberty’s) and ruffled hair. There was a saggy sofa, wobbly jellies, a ginormous wind-up gramophone and a vintage Rolls-Royce parked outside on the double yellow lines. Having lectured us on the purity of the Victorian Gothic as relevant to English culture, Professor Nevill then informed us that his great-uncle, 'Septimus Green' (nice one, Bernard, a marvellously inventive Victorian name, that) had, too, attended Cheltenham College. Returning to school after the holidays, we checked the leather-bound records in the College library. There was no Septimus Green.

I suppose Richard Griffiths steals the show— I mean, who can forget Uncle Monty? Or, perhaps, Withnail? Bruce Robinson based his script on his flat-sharing years in the late '60s: the character of Withnail (Richard E. Grant) inspired by a flatmate, the out-of-work actor Vivian MacKerrell, whose only film appearance (at least in a feature) appears to have been in Stephen Weeks' Ghost Story (1974), which we covered on Friday. Like Withnail (an Old Harrovian), MacKerell was a toff. A talented, hard-drinking thespian with matinée idol good looks, 'very bright' but, according to Robinson, a 'jack of all trades and master of none'. Too grand to accept lowly parts offered by his long-suffering agent. Vivian MacKerrell died of pneumonia in 1995.

Withnail's oh- so- English class elements are spot on, even if the subtle nuance may be lost on an audience from distant shores. The genteel squalor. ‘The insanity of the Stiff Upper Lip’. The watercolour of Harrow School (not Eton), the bad family portraits, the striped wallpaper and the Georgian mahogany furniture, the horror of the rodent-infested kitchen, that netherworld of the dusty, impoverished gentry, where the dysfunctional, down-on-their-luck upper-middle class merge into the ruthless, genuine aristocracy (born survivors, that lot), while in contrast, Paul McGann's practical (if less flamboyant) lower-middle class grammar school boy (based, I gather, on Bruce Robinson himself) may, actually, with a bit of grunt and hard work, get somewhere. And despite the dark British humour, or maybe because of the dark British humour, Withnail, I think, is ultimately an incredibly sad, or rather, poignant film. A film about friendship. A film about how people inevitably go their own separate ways. And some people, alas, are more successful than others.

Bruce Robinson and Vivian MacKerrell shared a rancid flat in Albert Street, Camden Town, the former haunt of Robert Elms and close to the location of the Camden Town Murders of 1907, as chronicled by Walter Sickert. It's also a stone's throw from the good burghers of Primrose Hill, near Alan Bennett's house (plus the lady in the van). The flat in Withnail is actually a decrepit house in Chepstow Place, on the Bayswater/Notting Hill borders— now, without doubt, a desirable property, echoing to the pneumatic drill of a plutocrat's basement dig out. The decrepit Jag— the unlisted star of Withnail— is said to have belonged to Lesley-Anne Down, Bruce Robinson's seriously gorgeous girlfriend and heroine of the original Upstairs Downstairs (1971-75). Mr. Robinson is also the author of the most extraordinary book. A book which reveals the true identity of Jack the Ripper.

But although Withnail & I is set, ostensibly, in 1969, it feels more like an edgy 1980s picture (filmed on the M25), and despite Danny the drug dealer's groovy gear, the street furniture's all wrong— or at least that's how I see it: a now vanished, eccentric England (‘Ealing on acid’), which met its demise in the late 90s: before political correctness, before Health & Safety, before London became bland, corporate, slick, packaged, squeaky-clean and brash— and m' dear, frankly, vulgar. When pubs looked like The Slaughtered Lamb: horse brasses, filthy prints of sepia (cracked glass) and chipped gloss ceilings in nicotine brown, where the locals played darts and downed a yard of ale, before the tyranny of the Gastro Pub (yawn) with the tasteful Farrow & Ball'd paintwork, acrylic abstracts and scrubbed pine— and 'portions' for the 'kids'.

Working at Phillips auctioneers in the very early 90s, Notting Hill was still a seedy and sometimes scary place, with eccentric antique shops off the Portobello Road: a fag-end of the old gangster culture, merging with the working-class Fulham of the 50s and 60s— as championed by The Gasworks restaurant, where High Society hobnobbed with the criminal classes. At Phillips, fruity RADA-educated actors would hang around the furniture saleroom, chatting up the porters. Lady Wotnot, the new business director, on a VIP clients' tour of the Phillips building (off New Bond Street), had to step over a pair of Irish lorry drivers gone berserk— a nose-to-nose confrontation on the floor. Or where, in the basement of my squalid, so-called 'studio' flat in Linden Gardens, we might watch a couple having sex through a grimy glass partition separating our 'kitchenette' from our neighbours, where nutritious mushrooms sprouted from the ceiling, lined in magnolia paper which looked like sick.

All this is a vanished world. There's also an element of urban paranoia in Withnail, even folk horror (there's somethin' narsty in the woodshed), the effete thespians up against a deranged tough in a hard-core Irish public house (Up the Provos!); the 'horror' of the countryside with its strange rural ways, beheading a chicken for a late supper, accepting help from a suspicious, inarticulate poacher (Michael Elphick), leaving a farm gate open (the cardinal tripper's sin), a dangerous bull on the loose. All this is similar to the brilliant All My Friends Hate Me (2021), the British urban-rural divide the theme of Straw Dogs (1971) and, to some extent, The Wicker Man (1973). And it's easy to forget how it was. Divided, just like today, but in a different way: when an Armani-clad 'yuppy' might get an instant ban from The Nun & Goat and there was a Gypsy pony market next to a railway siding opposite the Battersea Dogs' Home.

Bruce Robinson, apparently, had a problem with backer, George Harrison’s HandMade Films (producers of Monty Python’s The Life of Brian [1979]). They didn’t like the picture, didn’t get the black humour, finding it about as ‘funny as lung cancer’. Washing their hands of it, they left Bruce to his own devices, which may explain why the film is so good. I like Bruce Robinson, a man who loathes jokes and presumably stand-up comedy: the epitome of rock n’ roll aristocracy, a bibliomaniac and a fan of Charles Dickens. Watching Robinson’s interviews with the BFI, he’s entertaining, disarmingly honest, sometimes angry and intensely sympathetic.

I’m not sure if my nonagenarian mother has ever seen Withnail, but I suspect that it represents everything in the world that she finds disturbing: alcoholic, chain-smoking layabouts, (and even worse, layabouts living off Social Security), a squalid, rodent infested kitchen, bouncy sofas and predatory older men. But I hope she’s reading this. She’s a subscriber. And d’you know, she might actually enjoy it.

I watched Withnail & I (1987) on Amazon Prime Digital Download. Which cost me £5.99. And I’m glad that I did. It’s also available on DVD and Blu-ray. The DVD features artwork by Ralph Steadman, an added bonus. There’s also an illuminating documentary on the life of Bruce Robinson, which comes with my recommendation: The Peculiar Memories of Bruce Robinson. You can watch it on YouTube.

You’ve just been reading a newsletter for both free and 'paid-for' subscribers. I hope you enjoyed it. Thank you to all those of you who have signed up so far.

There are two options on Luke Honey’s WEEKEND FLICKS. Cinema for Grown Ups: ‘Paid-for’ subscribers get an extra exclusive film recommendation every Friday morning, plus full access to the complete archive— which is currently at film no. 84, and should list over a hundred films by the end of the year. It costs £5 a month (or £50 a year)— a bargain, frankly, when you compare it to a few cups of coffee, a packet of semi-legal gaspers, or a pint of beer in the pub. ‘Free’ subscribers get access to the Sunday newsletter, plus the ‘free subscriber’ films in the archive. Either option is a good bet. And when I get my act together, I’m planning to add a spoken voiceover (mine!) for paid subscribers.

I will be back next Friday. In the meantime, I hope you have a relaxing and cinematic Sunday.

.

“I fuck arses”? Who fucks arses? Maybe he fucks arses.

Excellent review and I am extremely envious of your wife for having been at the premiere. It’s a film utterly unlike anything else, screamingly funny but, as you say, also moving and sad. Richard E. Grant reciting Shakespeare to the wolves at the end is almost unbearable because you suddenly realise that somewhere in the damaged haze Withnail is a great performer.

Withnail is one of those films that's like a beloved destination- dangerous to revisit lest the remembered pleasure pales. You conjure it wonderfully well, Luke but dare I rewatch?