A real man of fashion and pleasures observes decency: at least, neither borrows nor affects vices; and, if he unfortunately has any, he gratifies them with choice, delicacy, and secrecy.

Lord Chesterfield (1694-1773), Letters to His Son, 27 March, 1743.

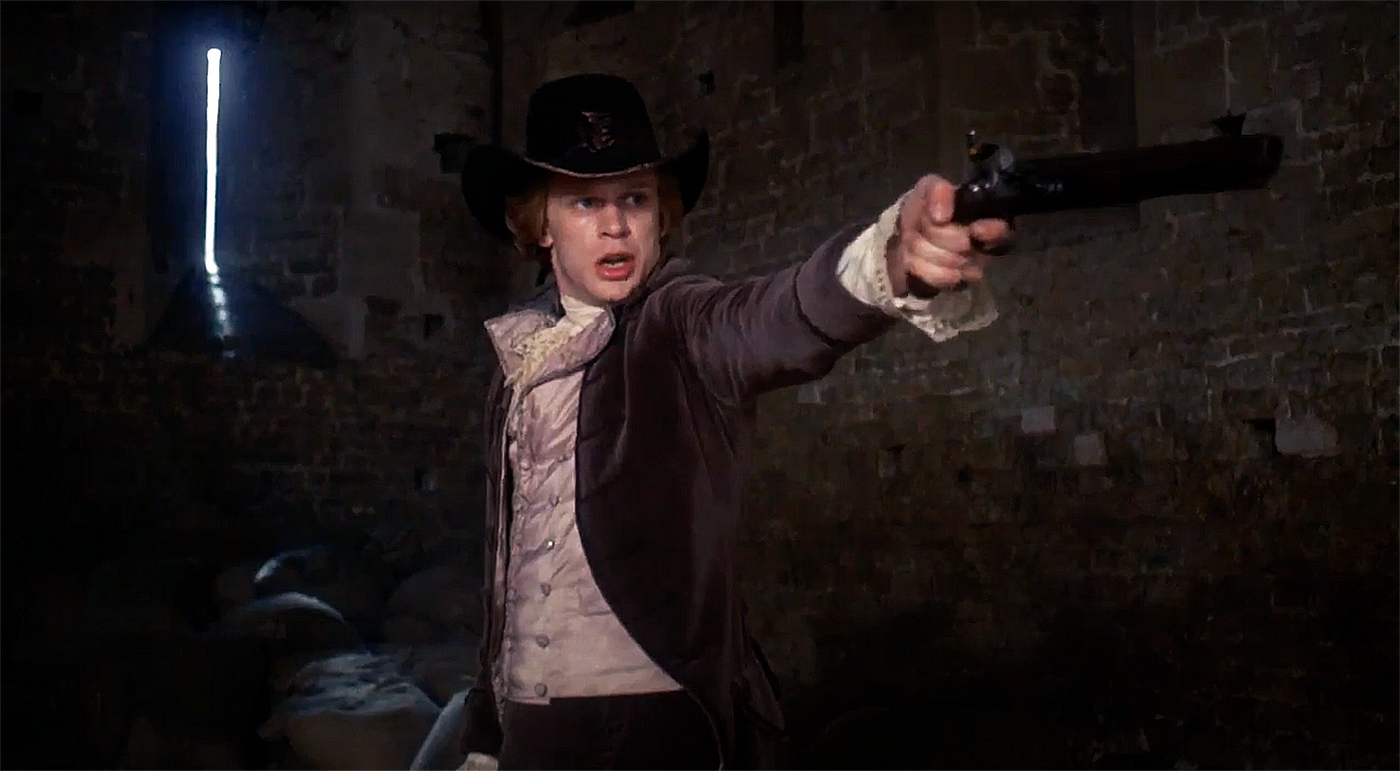

Aesthete’s films! I like the idea of a ‘Cinematic Beauty’ award. For visuals matter. They really do. After all, cinema is very much a visual medium. And we live in a world, frankly, which is consistently ugly. Or, at least, aesthetically challenging. From the top of my head, which films might be in the running? Elvira Madigan (1967) certainly — criticised by some as all style over substance, The Charge of the Light Brigade (1968), like an albumen silver photograph by Julia Margaret Cameron; Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975), The Duellists (1977), The Draughtsman’s Contract (1982), The French Lieutenant’s Woman (1981), perhaps, with its Pre-Raphaelite sensibility? The 1970s was a good time for this sort of thing, especially the cinematography, the artistic, romantic backlighting and the lens flare. And so we must add Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon (1975) to the list.

I must confess at this point that I have yet to read Thackeray's original novel, The Luck of Barry Lyndon, published in 1844. Shame on me — although Vanity Fair (1848) remains an all-time favourite. My understanding is that the novel is told from the point of view of Barry Lyndon himself, an unreliable narrator, while in the film, Sir Michael Hordern’s dry, rather worldly narration is as if spoken by Thackeray himself. And as with Vanity Fair, Barry Lyndon (Ryan O' Neal) is an anti-hero on the make, a plucky, happy-go-lucky Irish chancer, a 'low bred ruffian' (at least from an English aristocratic perspective), a man with pretensions to the landed gentry who styles himself as ‘Esquire’, and once he's scaled the upper echelons by marriage to Lady Lyndon (Marisa Berenson) — a prize catch, and the toast of Palladian Whig Society — reveals himself by the end of the film, to be not an especially nice chap. Surprisingly, critics at the time didn't really get Barry Lyndon. It was described as a 'coffee table movie'. Charles Champlin of The Los Angeles Times called it "the motion picture equivalent of one of those very large, very heavy, very expensive, very elegant and very dull books that exist solely to be seen on coffee tables. It is ravishingly beautiful and incredibly tedious in about equal doses, a succession of salon quality still photographs — as often as not very still indeed." The Washington Post wrote "It's not inaccurate to describe 'Barry Lyndon' as a masterpiece, but it's a dead end masterpiece, an objet d'art rather than a movie. It would be more at home, and perhaps easier to like, on the bookshelf, next to something like The Age of the Grand Tour, than on the silver screen."

Which, in my opinion, is hideously unfair, although we must, of course, allow others to have differing opinions. But, surely, the whole flippin’ point is that Barry Lyndon — a flexible mover and shaker — manoeuvres himself against a background of static, poised, upper class English Society; like an 18th century Conversation Piece, a Gainsborough, a Reynolds, a Hogarth, or an Arthur Devis?

“Barry - had now arrived at the pitch of prosperity and by his own energy had raised himself to a higher sphere of society. Having procured His Majesty's gracious permission, to add the name of his lovely Lady, to his own. Henceforth, Redmond Barry assumed the style and title of Barry Lyndon”.

That said, historically, Great Britain was a surprisingly fluid, practical and liberal society as compared, say, to 18th and 19th century Mainland Europe; one of its many strengths. For it might be possible for a man of lowly birth to reach the ranks of the Landed Gentry in three generations. Beau Brummell, after all, was the grandson of a valet and confectioner. Barry Lyndon’s peers hold him in contempt, less, I think, for his social status, and more for his uncouth manners: the blatant seduction of a maidservant in full view of Lady Lyndon and little Lord Bullingdon. Brawling in public during a recital of Bach’s Concerto for Two Harpsichords, BWV 1060 ain’t a good move either: if you want to ‘become’ a gentleman, you need to act like one. It’s not so much what you do, it’s how you do it. As Lord Chesterfield, that beacon of polished aristocratic cynicism, advised his son: a gentleman should gratify his vices with ‘choice, delicacy and secrecy’.

John Alcott’s cinematography is clearly influenced, and in imitation of, 18th century English painting. There’s a stableyard scene, with a handsome Thoroughbred. Stubbs immediately springs to mind. And Marisa Berenson’s a stunner. Seriously. A Reynolds beauty. A spitting image of Georgiana Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire. Somehow she just breathes Eighteenth Century. It’s as if she was made for the stacked wigs, the powder, the beauty spots. There’s a marvellously cool, aristocratic detachment and deportment. She doesn’t say much, which is probably a good thing, as there’s a smatter of a slight American or some sort of international jet set accent, despite her English ‘education’ at Heathfield School, Ascot. Or maybe that doesn’t matter? Look, please don’t get me wrong. I’m a huge fan.

Which takes me, indirectly, to the lighting. Oh, the lighting! Kubrick recreates the intimacy of the 18th century gambling salon, filmed entirely by candlelight, using ‘super-fast’ lenses developed for the NASA space programme — a revolutionary innovation for the time. The other scenes were lit to deliberately mimic natural light.

And there’s a terrific supporting cast. Leonard Rossiter as the cowardly Captain Quinn, Patrick Magee as the roguish Chevalier de Balibari, Steven Berkoff as Lord Ludd, Jonathan Cecil as an effete British officer, Leon Vitali as Lord Bullingdon, and the late, and always wonderful, Murray Melvin as Lady Lytton’s poker-faced private chaplain. And for those of us fascinated with the intricacies of 18th century duelling, Barry Lyndon provides a useful self-help, DIY manual:

So there you go. Barry Lyndon (1975). A taster. Of course, there is a great deal more to say about the film, but I am about to run out of word count. I hope you enjoy it as much as I did. And we can, most certainly, add it to the very best of the WEEKEND FLICKS. film list.

Okay, let’s have a recap. That was film no. 121. We’re now tantalisingly close to 1,000 subscribers. So thank you. I gather Substack send you some sort of email badge when you pass this magic figure, which sounds a bit like Blue Peter. I watched Barry Lyndon (1975) on Amazon Prime Video, but, as ever, it’s available on DVD and Blu-ray. Barry Lyndon might look stunning, I suspect, on Blu-Ray. I must get my act together and save up for a Blu-Ray machine. Or turn our basement into a splendidly vulgar private cinema. That would be good. I will be back on Friday with a film recommendation for the ‘paid subscribers’ (£5 a month, or £50 a year), and I’m planning two extra ‘lovey-dovey’ posts to celebrate Valentine’s Day, which will be free. Look out for those. I’m in the mood for love.

Seeing this in first release on the big screen was amazing, it was like watching a series of moving images captured in oils on canvas, there was so little dialogue compared to most films, but my buddy and I were still shushed by a woman I the next row as we critiqued inaccuracies in the depiction of the tactics of the period (we felt they fired too soon and should have been closer).

A superb film! everything about it was good form the acting, the clothes, interiors and music! I understand that it was filmed without artificial light. On a similar plane The Go Between is one of my favourites and of course Un Homme et une Femme though that is set in contemporary times.