Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (1968)

"Here we are children, come and get your lollipops, lollipops! Come along my little ones..."

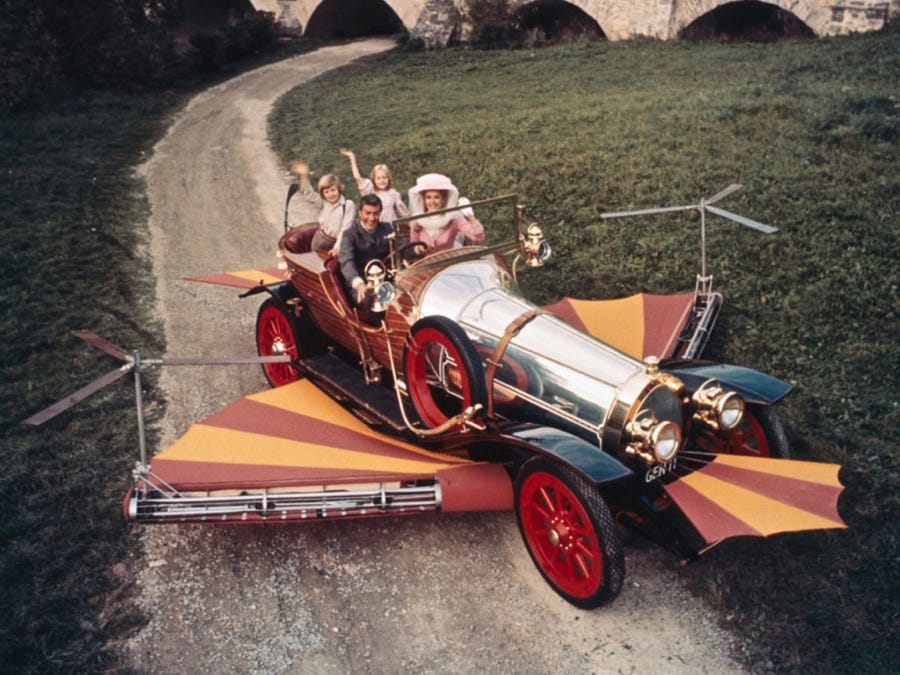

These stories are affectionately dedicated to the memory of the original CHITTY-CHITTY-BANG-BANG, built in 1920 by Count Zborowski on his estate near Canterbury. She had a pre-1914 War, chain-drive, 75 horse-power Mercedes chassis, in which was installed a six-cylinder Maybach aero engine — the military type used by the Germans in their Zeppelins…

She had a grey steel body, with an immense polished bonnet eight feet in length, and weighed over five tons. In 1921 she won the Hundred M. P. H. Short Handicap at Brooklands at 101 miles per hour, and in 1922, again at Brooklands, the Lightning Short Handicap. But in that year she was involved in an accident and the Count never raced her again.

From Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang: The Magical Car by Ian Fleming, Jonathan Cape [1964].

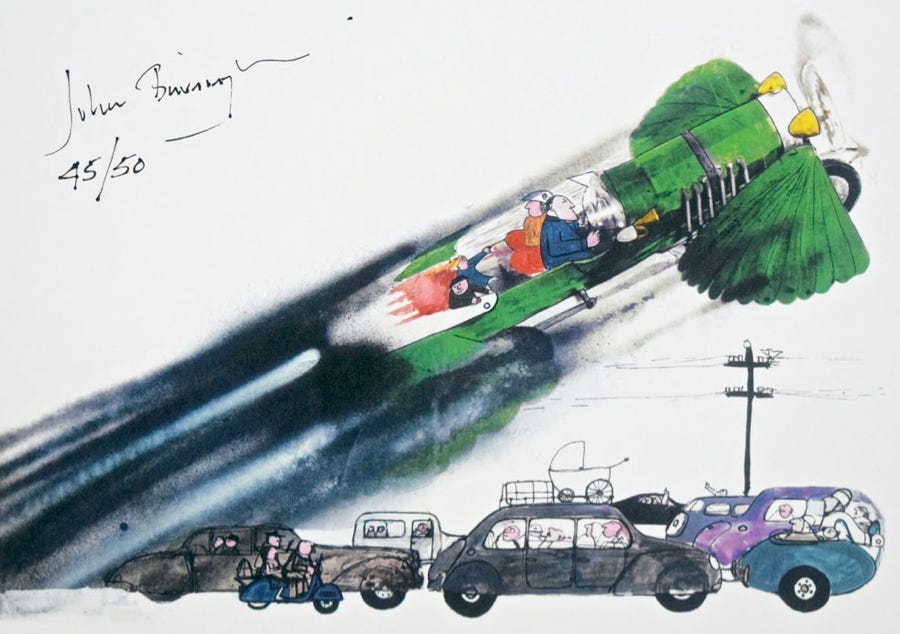

There’s more to Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (1968) than first meets the eye. And there’s so much to write about. You might even call it the Bond film which got away. First, it’s based on Ian Fleming’s children’s book, published posthumously by Jonathan Cape between 1964-5, in three volumes, with evocative illustrations by John Burningham. Fleming wrote his story in longhand (Annie Fleming had confiscated his portable typewriter) while convalescing in hospital from a heart attack, and, rather poignantly, based it on the bedtime stories he had made up for his troubled eight-year son, Caspar. Tragically, Caspar took his own life in 1975.

Although Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang: The Magical Car is, in many ways, a straightforward cops n’ robbers job, the book also includes many of Fleming’s obsessions: it’s a key work in the Fleming canon. Like Fleming, Caractacus Pott (Potts in the film) holds the rank of Commander in the Royal Navy (albeit the Wavy Navy, the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve). The English county of Kent, St Margaret’s Bay (where Fleming and Noel Coward had weekend beach houses, both in the Art Deco taste), the fading stucco’d elegance of Normandy’s seaside towns (Casino Royale), the shipwreck fest of the Goodwin Sands, (where until 2003, at low tide, an annual cricket match took place), the ‘top secret’ recipe for fudge: all these things are immensely Fleming. Plus, of course, the miraculous, gadget-laden car itself, based on the monstrous, chain-driven, aero-engined Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang (s) as raced by Count (Louis) Zborowski in the 1920s.

Louis Zborowski is an interesting character. Despite the Polish surname, he was actually British, born of rich American parents. The title was bogus, assumed by Louis’ father. But in any event, Zborowski had pots of money, inheriting Higham Park in Kent on the death of his mother. And I’ve nicked a rather juicy statistic from Wikipedia: “Upon [his mother’s] death in 1911, 16-year-old Zborowski became the fourth richest under-21-year-old in the world.” In 1924, at the Italian Grand Prix in Monza, Zborowski’s eight-cylinder Mercedes skidded on a curve and turned over. The count was pulled from the wreckage and died soon afterwards.

And there’s that Fleming obsession with money, with gold, with treasure and riches — and never-ending wealth. Eon Productions, purveyors of Bond, held the rights to Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang. So the 1968 film was produced by Cubby Broccoli and directed by Ken Hughes. Following the financial success of You Only Live Twice (1967), Eon brought back Roald Dahl to write the screenplay. And there are so many Bond parallels: Gert Fröbe (Goldfinger) stars as Chitty’s teutonic villain, Baron Bombast. Anna Quayle is the Baroness (Frau Hoffner in Casino Royale [1967]), Desmond Llewelyn of Q Branch puts in a dodgy performance as nasty old Mr Coggins, the scrap metal merchant; Ken Adam designed the car (s) and the sets, and then there’s the one and only Truly Scrumptious (played by the wonderful Sally Ann Howes, number plate CUB 1). If ever there’s a Bond girl’s name, that’s it, if anesthetised for the kiddywinks — although Venetia Honey gives it a run for the money. And there’s a Roald Dahl/Ian Fleming hybrid thing going on, which, again, is kinda interesting. Toot Sweets (Crackpot Whistling Sweets in the book) and a chocolate factory. I mean, how Dahl can you get? And the terrifying child-catcher (played by the wonderful Sir Robert Helpmann, on loan from the Royal Ballet), and all that Ruritanian Vulgarian stuff — which turns me on — filmed at Neuschwanstein Castle, Ludwig II’s Wagnerian fantasy in Bavaria. That said, in time-honoured cinematic tradition, there were all sorts of problems with Dahl’s script, “they took my script and never used a word”, and Ken Hughes and Richard Maibaum (credited as a writer on no less than 13 Bond films) had to rescue it. Hughes claimed, subsequently, to have written “every f*****g word.”

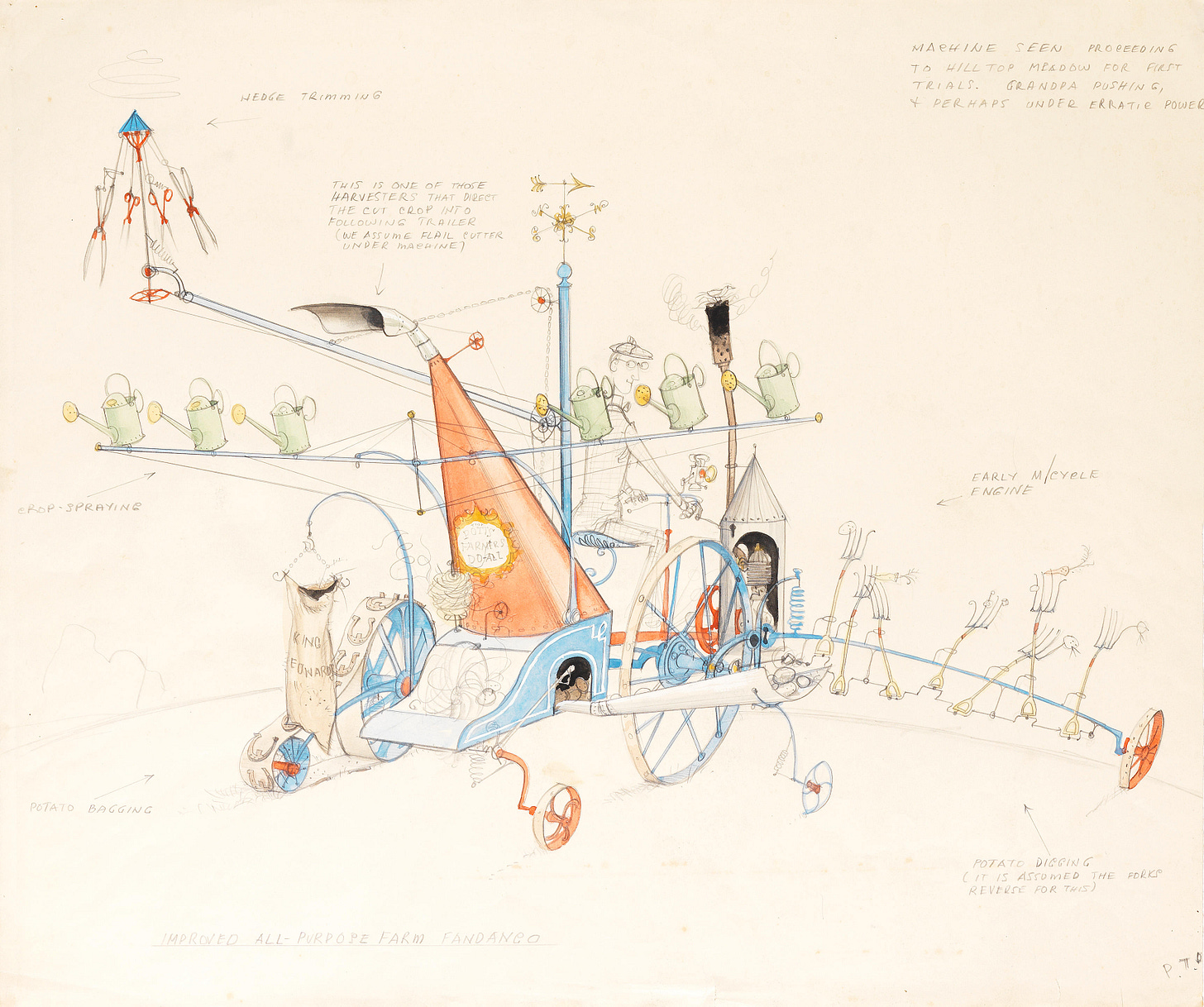

I know Chitty goes on for too long, and I’m never entirely convinced by Lionel Jeffries’ coy and slightly embarrassing performance as the arthritic Potts Senior, but Chitty remains one of my favourite films. It has to be. It’s interesting on so many layers. Caractacus Potts’ house was filmed at the much-loved Cobstone windmill on the ridge above Turville, a familiar landmark in the Chiltern Hills, about thirty miles or so to the North West of London on the Buckinghamshire/Oxfordshire border. John Mills’ daughter, Hayley, I think, lived there at the time. And this eccentric hovel, with bare rafters, leaking roof and creaking wooden machinery is full of invention, courtesy of Ken Adam’s marvellous set design, with its Victorian bric-a-brac: the Pollock’s toy theatres, oil lamps and discarded union jacks — and of course, the wonderfully wacky Victorian-esque inventions (remember the Automated Breakfast Machine?) designed by inventor, illustrator and writer, Rowland Emett. You may remember Emett as the creator of Battersea Park’s Far Tottering and Oyster Creek Railway for the Festival of Britain in 1951. Emett’s work reminds me very much of Ronald Searle’s glorious illustrations. Dead trendy in 1968. Whimsical Victoriana. The late 60s/early 70s obsession with the Late Victorian and Edwardian periods — the supposedly Golden Age of the years leading up to the outbreak of the First World War, especially in the public imagination — that Arcadian, long hot summer of 1914. Chitty has this in spades. As do The Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines (1965) and The Assassination Bureau (1969). Spiked helmets, German Oompah Oktoberfest bands, Zeppelins. Beer Halls and Lederhosen. Gingerbread. The cobbled streets of Rothenburg ob der Tauber. Pickelhaube Chic.

Unlike the book, which is set at the time of publication, the film (like Mary Poppins [1964]) is set in 1910, or thereabouts. And that’s an excuse for 1960s Edwardiana — especially in Lovely Lonely Man, sung by Sally Ann Howes (black mascara and backlighting) on the green croquet lawns of Heatherden Hall, Pinewood’s finest: all white summer frocks, parasols, garlanded hammocks, white swans, composition urns and ivied balustrades. It’s actually all a bit Cecil Beaton. As a boy, I used to find this number far too girly and lovey-dovey, a time to cringe behind the sofa. Now as a grown up fifty something, in Late Late Youth, I like it immensely, and find it touching — it’s a terrific song — which just goes to show that all you need is time. And all you need is love. Lovely Sally Ann Howes. Pitch Perfect. A big Broadway star at the time. And despite her relatively advanced age (thirty seven) she truly nails it as Truly. As does Dick Van Dyck’s Caractacus — despite the transatlantic accent and the bendy legs, or perhaps because of the transatlantic accent and the bendy legs. I mean, they just work, those two. Sally and Dick, not just his legs. Can you imagine the film without them? And with my objective hat on, the effortlessly elegant music of Robert and Richard Sherman, the Sherman Brothers, is truly brilliant. Such a talent. Especially in Doll On a Music Box, the Van Dyck/Howes duet, where the Truly Scrumptious theme effortlessly harmonises into the whole. Beautifully done. Like clockwork. And the touching bitter-sweet, music-box beauty of Hushabye Mountain, which, as with Lovely Lonely Man, still chokes me up, even now, all these years later — and makes me blub.

And talking of hiding behind the sofa, Robert Helpmann’s child-catcher was truly, utterly terrifying. If you were eight years old. I’m sure others will agree. Something primeval going on there. Oh the horror! That net, that carriage, and that ‘orrible plasticine nose! This seems like a genuine Dahl touch, (altho’ Ken Hughes claimed to have invented the character), a nod to the Brothers Grimm and the Mitteleuropean fairy story. As in the disturbing Hansel and Gretel, the children are entrapped in an animal cage. And the sweeties incidentally, are so, so Sixties are they not? Like something from The Magic Roundabout or The Prisoner? With the striped sticks of walking stick rock (curved handles), glass jars of toffees, the idea of an old fashioned sweet shop, and an avuncular Bavarian toy maker, as in Pinocchio, played beautifully by good old Benny Hill. “Lollipops! Lollipops! Kiddywinks, come and get your lollipops!”

So there you go. Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (1968). With the Easter break on the horizon, I’ve got some extra, juicy posts in the planning for the paid subscribers, so, as I’m in a good mood, and the sun here in old London Town is shining (not), I’ve made today’s post a bonus post, as a special treat — which means that it can be read by all. I await your comments with trepidation. Like The Railway Children (1970), Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (1968) is a key film for a generation. Squirreled away in our collective memories, of tea-times, languid Sundays afternoons and rainy Bank Holidays past.

I watched Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (1968) on a Special Edition DVD, which includes all sorts of extra goodies and bonus features, including a lovely period documentary about the work of inventor and artist, Rowland Emett, Cartoonist at Home (1963), which you can also watch on YouTube. And, of course, Chitty is also available on Amazon Prime Video, and, I expect, other digital channels.

Before I go, a quick word about the paid subscription, which costs £5 a month or £50 a year. Paid subscribers get their own special post on Friday mornings, extra bonus posts on High Days and Holidays, and access to the entire archive — which is now running at some 131 films. Sunday morning’s post is free, and can be read by everybody and anybody. Until then. Auf Wiedersehen…

I can't believe I've never seen this movie! Too many films to watch... Argh! If it wasn't 1am I'd start watching it right now. Tomorrow, then. Ok.

One more memory fragment. I remember seeing it at the pictures on release and the interval break happened just as the car went over the cliff. The second half began with it magically sprouting wings and flying to safety. Never was an intermission so filled with anticipation.