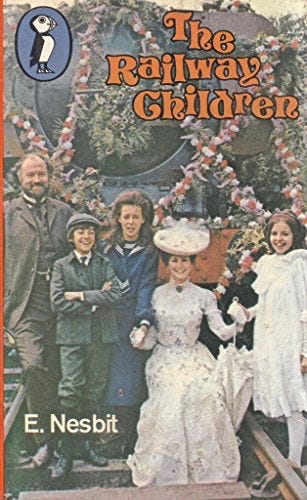

The Railway Children (1970)

"Daddy, My Daddy!"

They were not railway children to begin with. I don't suppose they had ever thought about railways except as a means of getting to Maskelyne and Cook's, the Pantomime, Zoological Gardens, and Madame Tussaud's. They were just ordinary suburban children, and they lived with their Father and Mother in an ordinary red-brick-fronted villa, with coloured glass in the front door, a tiled passage that was called a hall, a bath-room with hot and cold water, electric bells, French windows, and a good deal of white paint, and 'every modern convenience', as the house-agents say.

E. Nesbit, The Railway Children (1905).

Before we begin, a quick chat about our programme for Advent. For Christmas is not only a time for ghost stories but a time for cinema. I’ve got a cracking Christmas lineup for you — including a sprinkling of sparkling extra content, starting with a ghostly bonus post for paid subscribers on Wednesday. In the meantime, here’s my first recommendation: The Railway Children (1970)— one of my all-time favourite films. This is more or less the first time I’ve written about it— even on Instagram. And there’s much to say. I hope you enjoy it.

The late great Bryan Forbes once said, in a television interview, that The Railway Children made him cry whenever he saw it. I'm glad he said that as two scenes in particular — Roberta's birthday party and the reunion with her father (at the end of the film) — reduce me to a blubbering, sobbing wreck. Every time. Without fail. And I've seen this film many, many times. During his stint as the head of EMI-MGM Elstree, Forbes was the driving force behind The Railway Children, both as producer and financial backer, a short-lived tenure which also produced Frederick Ashton's ballet film, The Tales of Beatrix Potter (1971) and Joseph Losey's The Go-Between (1971). "Thank you, Mr. Forbes!" say the children during the rolling credits (as they break the fourth wall in that whimsical style so reminiscent of the early 70s). And we do, indeed, need to thank Mr. Forbes, as The Railway Children (1970) is a masterpiece of British cinema. And I stand by that.

The Railway Children (1970) was Lionel Jeffries' directorial debut, which makes it even more remarkable. Sometimes, and it's a rare occurrence, a film will come together to create something nearing perfection: the direction, the cinematography, the editing, the acting, the costumes, the locations, and the music all somehow gel into one glorious whole. Which explains why The Railway Children is such a beautifully constructed gem. Helped too, by E. Nesbit’s prose and her original conceit — for E. Nesbit was a remarkable woman.

I met Lionel Jeffries once — except that I didn't. In 1974, my parents entered me for a colouring competition in The South Buckinghamshire Advertiser; the kiddywinks encouraged to colour-in a cartoon of the 'Gravel Monster', a satirical depiction (in the style of Punch) of local capitalist greed — for nasty, noisy, smelly gravel pits were to be dug close to the sprawling Edwardian Arts & Crafts houses of Gerrards Cross, with their tennis courts, swimming pools and croquet lawns as smooth as baize. I can't remember exactly what I came up with, but being a creative, arty, and restless child, and handy with a felt-tip pen, I have no doubt that my monster was covered in toxic pink spots — as if it had Scarlet Fever. Mr. Jeffries was to present the prize. A crisp, blue five-pound note. With the Queen's head on the front and the Duke of Wellington to the reverse. Oh, great excitement! Except that Mr. Jeffries failed to turn up. Instead, and much to my intense disappointment and distress, the prize was presented by a local Liberal Councillor, who, curiously, makes a fleeting appearance in one of my all-time favourite books, Laughter from a Cloud (1980), the amusingly crusty memoirs of Laura Charteris, Ian Fleming’s sister-in-law, later Duchess of Marlborough:

I scarcely know any of my neighbours in this suburban area, but two couples are great friends. Mr. Burrage is a scrap merchant… sometimes they take me dog-racing in Slough… My other great friends are a Liberal Couple… happy to argue about politics.

For the Duchess lived nearby, at Gellibrands, a fascinating 17th-century house in the Buckinghamshire brick-and-timber tradition, newly decimated by the M25. I only mention this — in passing — to stress quite how famous Lionel Jeffries was at that time, both as a character actor and a successful film director. Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (1968) and The Railway Children saw to that.

But despite the phenomenal success of The Railway Children, Lionel Jeffries' career as a director was, frankly, a trifle patchy. There's the much-loved The Amazing Mr Blunden (1972) based on Antonia Barber's The Ghosts (1969), a distinguished children's novel short-listed for the Carnegie medal; there's Baxter! (1973), a film I have yet to see thanks to its sparse distribution, yet described by one critic as a 'minor masterpiece'; the wunderwerk which is Wombling Free (1977) and The Water Babies (1978), a rather strange work of live-action animation. And that's about it. But Jeffries — very sensibly — pitched The Railway Children to Forbes more or less 'as is', with a script based on Edith Nesbit's original book of 1905. A wise move, as Nesbit writes like a dream. Here's Noel Coward on Nesbit, his favourite author and stylist in the English language:

E. Nesbit knew all the things that stay in the mind, all the happy treasures. I suppose she, of all the writers I have ever read, has given me over the years the most complete satisfaction and, incidentally, a great deal of inspiration. I am glad I knew her in the last years of her life.

There's an economy and precision to Nesbit's writing: Nesbit paints a picture with a few carefully chosen words. As Noel Streatfeild puts it, 'She had an economy of phrase and an unparalleled talent for evoking hot summer days in the English countryside.' And, just like Terence Rattigan, there's an underlying Englishness, 'the English vice of emotional containment' as Michael Billington described it (altho' I'm not sure that I would describe this as a vice, necessarily). It's this English repression (one might call it the Stiff Upper Lip), the 'emotional containment' of Dinah Sheridan's reserved middle-class Mother, that makes The Railway Children so affecting. Like Alfred Dreyfus, Father (a Foreign Office official), beautifully portrayed by Iain Cuthbertson ('an Englishman's home is his castle'), is an innocent sent to prison, accused of stealing diplomatic secrets, forcing the family to give up their comfortable London villa (in the film, just off Flask Walk, Hampstead) in exchange for a shabby cottage in rural wherever (in the film, Yorkshire). False imprisonment is one of Nesbit's significant themes; the sweet Russian the children take in from the cold is most probably a Socialist-Revolutionary, for Nesbit was a political activist and co-founder of the Fabian Society. And the kindly Old Gentleman the children befriend, he of Mr. Kipling Makes Exceedingly Good Cakes (Norman Shelley), a director of the fictional Great Northern & Southern Railway, is most likely a classic Victorian Liberal of the old school, a progressive and leading member of the Reform Club and a campaigner for social justice.

Nostalgia is, of course, absent from the original Nesbit — in the sense that her book is set in her own time; although, as Coward and friends point out, Nesbit’s books have an emotional sense of place (from the point of view of a late 20th-century readership); but then nostalgia is the most English of traits. As with the music of Elgar, a wistful yearning for the past, for what has been, for what might have been, melancholy, a sense of loss. The snag, of course, is that nostalgia and sentimentality can go hand in hand, even to separate English sentimentality from the saccharine of Disney. Evelyn Waugh — oh, so sharp! — understood this only too well. The danger of English charm. Remember Charles Ryder’s drunken luncheon with Anthony Blanche in Brideshead Revisited (1945)? Here’s Antoine (the foreign observer) in action:

You see, my dear Charles, you are that very rare thing, An Artist. Oh yes, you must not look bashful. Behind that cold, English, phlegmatic exterior you are An Artist. I have seen those little drawings you keep hidden away in your room. They are exquisite. And you, dear Charles, if you will understand me, are not exquisite; but not at all. Artists are not exquisite. I am; Sebastian, in a kind of way, is exquisite; but the Artist is an eternal type, solid, purposeful, observant — and, beneath it all, p-p-passionate, eh, Charles ?

“But who recognises you? The other day I was speaking to Sebastian about you, and I said, ‘But you know Charles is an artist. He draws like a young Ingres,’ and do you know what Sebastian said? ‘Yes, Aloysius draws very prettily, too, but of course he’s rather more modern.’ So charming; so amusing.

“Of course those that have charm don’t really need brains.”

On the other hand, with my historian's cap on, one might argue that social change (between 1905 and 1965) was as profound and had a more significant impact, say, than between 1974 and 2024, despite the internet. Two world wars saw to that. This explains, to some extent, the Seventies obsession with the Late Victorian and Edwardian age — from Laura Ashley to the paintings of Helen Bradley (And Miss Carter Wore Pink), from the Habitat catalogue to the Christopher Wray Lighting Emporium, from Peter Weir's Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) to Penelope Farmer’s novel, Charlotte Sometimes (1969), both set in a girl's boarding school, the first in 1900, the second during the Spanish 'flu epidemic of 1918.

For somebody born in 1900, the contrast between a gaslit childhood (an Edwardian Never-Never Land) and Post-War Britain must have been startling. Muffin Men, Hansom Cabs and the Gold Standard replaced by the Beatles, Concorde, a rebuilt Coventry Cathedral and Spaghetti Junction — Oh, Brave New World! And all this in seventy years! But it may explain why The Railway Children is so affecting. Would The Railway Children move us to quite the same extent if, say, it had been set in the 1920s? Or the 1950s? No. If Peter Waterbury is ten years old in 1905, that makes him twenty years old in 1915. The year that witnessed terrifying casualty rates in the trenches, especially amongst the junior officers. Consciously or unconsciously, the trauma of the Great War looms over those of us who grew up in the 1970s — referenced so often in the popular television culture of the time, Doctor Who and Sapphire & Steel (1979), and in the period dramas: Upstairs Downstairs (1971-75), The Duchess of Duke Street (1976-77) and Testament of Youth (1979), based on Vera Brittain's experiences as a VAD nurse on the Western Front. We have the benefit of hindsight; we know what is to come. Which at the same time, creates, perhaps, the illusion of a Golden Age that never existed, an age, in truth, of strikes, social turbulence and political turmoil. An age which ends in August 1914. There's a moving passage in E. H. Shepard's Drawn from Memory (1959), the beautifully written and illustrated autobiography of Shepard’s London childhood. The book is set in St John’s Wood, during the 1880s, except for this brief passage. The sudden shift in time makes it even more poignant:

Twenty-nine years later I was to hear the words of those hymn tunes again. They were sung by Welsh voices on a dusty shell-torn road in Picardy, as battalion of Welsh Fusiliers marched into battle. I was standing by the roadside, close to what had been Fricourt, when they passed. I was grateful for their song. It seemed as if the men were singing a requiem. For that day I found my dear brother’s grave in Mansell Copse. The spot was marked by simple wooden crosses bearing the names of the Fallen roughly printed on them. It was, and is still, the resting place of over two hundred men of the Devons who fell that Saturday morning in July 1916.

Ernest Shepard, from Drawn from Memory (1957).

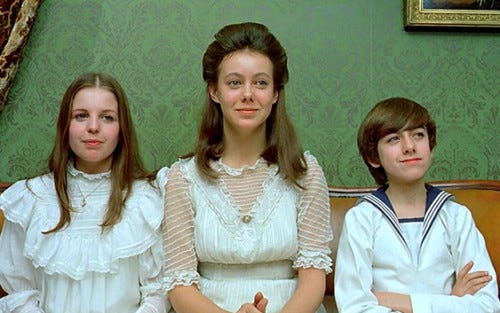

And yet, surprisingly, despite The Railway Children's reputation as a 'family classic' (a sometimes patronising phrase I'm never entirely convinced by), there's a touch of the New Wave to the editing and direction, which viewers might otherwise miss. During the birthday party scene, Jenny Agutter glides into the room on a skateboard (although one wonders if she might actually be sitting on some sort of rig), a technique used in Jacques Demy's The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964), and then, in the final scene, on the station platform, there's an innovative use of sound (intentional?) with Bobbie's reverberating, echoing cry paired to Johnny Douglas' deeply moving score. It is, of course, this haunting ending which everybody remembers, and deservedly so — the love of an adolescent girl (on the cusp of womanhood) for her father, the loss of innocence.

At that moment, Bobbie grows up. She bears the weight of the world on her shoulders. And that's why I think it's so moving. I made my thirteen-year-old niece watch The Railway Children, and her only response, once the film had finished and the rest of us had dried our tears, was 'soppy'— or an equally derogatory word to that effect. But then, I think, The Railway Children is a film best seen — and understood — by the middle-aged, especially the Anglophile middle-aged, a film, perhaps, which has a greater resonance with those of us who grew up in the Seventies, a time, even then, lurking, still, in the shadow of the Great War.

I watched The Railway Children (1970) on DVD. There have been at least six adaptations for radio, television and film. For the record, I’m also a fan of the Carlton made-for-television film of 2000, transposed to the Sussex countryside, with Jemima Roper as Bobbie, Jenny Agutter as Mother, Michael Kitchen as Father and Dickie Attenborough as the Old Gentleman. It’s a wonderful production, and comes with my recommendation.

Today’s post is Film No. 101. There are two options on Luke Honey’s WEEKEND FLICKS. Cinema for Grown Ups: ‘Paid-for’ subscribers get an extra exclusive film recommendation every Friday morning, plus full access to the complete archive.

It costs £5 a month (or £50 a year) — a bargain, frankly, when you compare it to a few cups of coffee, a packet of semi-legal gaspers, or a pint of beer in the pub. ‘Free’ subscribers get access to the Sunday newsletter, plus the ‘free subscriber’ films in the archive. Either option is a good bet. And when I get my act together, I’m planning to add a spoken voiceover (mine!) for paid subscribers. That’s for the New Year.

I’ll be back on Wednesday, with my first bonus Christmas post for the paid subscribers. A ghostly tale which will give you the jitters. Guaranteed. Until then, adieu…

Can't watch it. Just can't. It's too upsetting. That moment. I used to recite the last minutes it with my friend the wonderful Deborah Kiely. Then she was taken from us all at 40. We would watch THE WHOLE FILM waiting for that moment. Even thinking about it now makes my eyes sting. Such power. Why? How? Thankyou Luke for featuring it.

My favourite film of all time too - I am sobbing just reading your words - thank you xxxxx