Goldfinger, he's the man

The man with the Midas touch

A spider's touch

Such a cold finger

Beckons you to enter his web of sin

But don't go inShirley Bassey, Goldfinger.

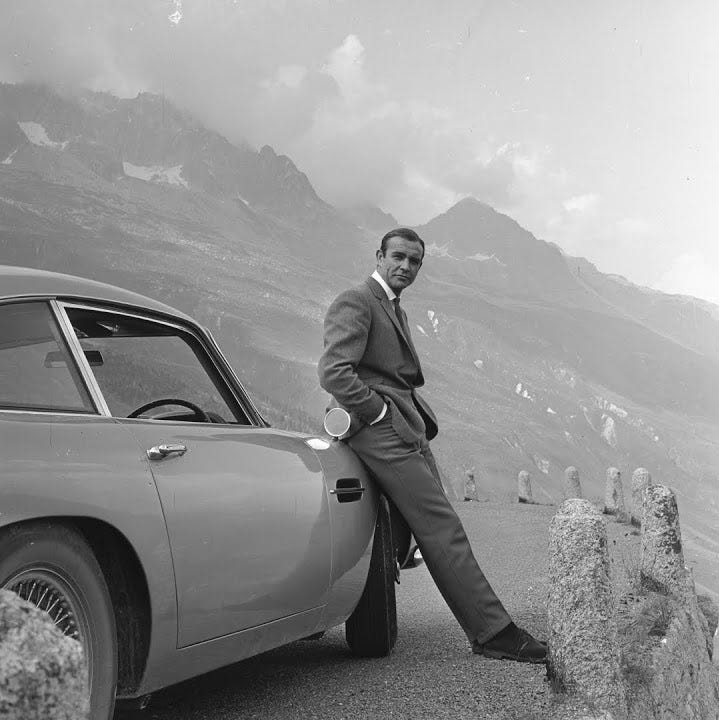

Is Goldfinger (1964) the best of Bond? Most possibly, yes, although, as readers may remember, Peter Hunt’s On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969) remains a personal favourite. Guy Hamilton’s Goldfinger, on the other hand (I refuse— on pain of cancellation— to use the dreaded word, ‘iconic’), is undoubtedly, or most probably, the Bond’s Bond, partly because it establishes the things we have grown to love about the franchise— or so numerous 007 obsessives like to remind us. Bond’s dashing Bentley special is ditched for a silvery Aston DB5, tick. There’s lots of gadgetry (at least in the car), tick. The US Marines lead an assault on Fort Knox, tick. There’s blow-dried humour (or at least a toupée), tick, and design genius Ken Adam goes to town on his brilliant sets, tick. However, playing the role of devil’s advocate, I need to point out— sorry, boys— that despite Shirley Bassey and all that, From Russia With Love’s titles are equally Bond-esque, that, despite the Furka pass, Goldfinger’s locations are hardly ‘exotic’ (South Buckinghamshire, Florida and Kentucky?) and that Gert Fröbe’s Goldfinger (as much as I like him) is really more of a corporate baddie gone wrong (gilt-edged dinner jacket) than Charles Gray’s marvellously urbane, dastardly villain of world domination (plummy white Persian and cigarette holder)?

But Goldfinger (1964) was the first Big Budget Bond. Costing the same, I gather, as the first two films put together, it went nuts at the box office and premiere, when, according to The Kinematograph Weekly, ‘5,000 fans fought the police outside the Odeon theatre’ in Leicester Square. It was also the first Bond to flog film-related merchandise: action figures, jigsaws, lunch boxes, board games, and, apparently, ‘dress’ shoes, whatever that means. Even ten years later, in the playground, little boys in shorts and muddied knees bragged about the James Bond Corgi DB5 they had been given for Christmas. With an ejector seat that ‘really worked’. I never had one. And it’s probably warped me for life. My mother (pursed lips) disapproved of Mister Bond and All His Works, thinking the films unsuitable for a ten-year-old. It wasn’t until 1977 that I made it— finally— to The Spy Who Loved Me (under adult supervision), by which time the Aston had been replaced with a white Lotus, which leaked, both on screen and in real life. I felt cheated.

Anyway. Goldfinger opens with a terrific sequence: the aerial shot of the Fontainebleau Hotel (a luxury modernist beach resort in Miami), all skyscrapers and swimming pools, set to John Barry’s sweeping big-band soundtrack. And it’s loud, really loud, a swamp of sound (a trick used by Losey and Legrand at the beginning of The Go-Between). It sets the scene. American consumerist power in the 1960s. This must have seemed exotic and glamorous (despite my previous observations) to a British audience reared on the austerity of Lord Woolton Pie, when actually, by today’s standards, it’s really just a group of healthy, well-tanned people clustered around a concrete swimming pool— actually not unlike one of those package deals at a budget resort on the Red Sea.

And that whole ‘leisure’ thing. It’s so corporate. The American Dream. I’m sure the concept of ‘leisure’ comes from this post-war period. Sell your soul to the corporation, and the corporation ‘rewards’ you with allotted leisure time (on their terms), which you spend with other executive families in executive resorts with executive swimming pools and executive golf courses. Build debt with your executive credit card before returning to your executive desk. While your executive wife returns to a life of Bridge, coffee mornings and dinner parties. Death by Prawn Cocktail. My point is that ‘leisure’ is defined by work. During the 19th century, the upper and upper middle classes didn’t need to work (you lived off rents, Bank of England investments, East India Company shares or whatever), so there was no need for leisure. And your life revolved around country sports, property management, local tittle-tattle, politics, philanthropy, or, in some cases, scientific experimentation (Sir George Cayley Bt.). Leisure is a by-product of work— which leads me, inevitably, to golf.

Golf’s a big deal in Goldfinger. The sporting bits were shot at Stoke Park Golf Club in Stoke Poges, a South Buckinghamshire village on the outskirts of Slough, four miles from Pinewood Studios. I must confess, at this point, that I’m allergic to the game. Like that endearing wunderwerk, Howard’s Way (1985-1990), golf has all the glamour of the suburbs. Polyester City. The natty checked pants. The tupperware buggies. The ridiculous hats. The semi-detached snobbery of the golf club. Sucking up to the Club Captain— actually, not unlike the pecking order on a Mediterranean cruise. The anaesthetized ‘countryside’, with its perfect, putting-grade grass, drenched in chemicals. And yet, and yet, I understand its considerable appeal— especially to middle-aged men, an under-championed and oft-maligned group of which I am unashamedly a member— the anally retentive control freakery (as with fishing, man sheds, ‘moddle’ railways, classic cars and the perfect lawn), the collector’s mentality, the YouTuber’s wet dream: amassing all the gear, the expensive kit, the jargon: the Mashie Niblick, the Birdie, the Double Bogey, the Mulligan, the Hole in One; the fresh air— and the masculine competition. And all that stuff about handicaps, sandbaggers and pars— which I don’t understand. It’s like the Masons. But then golf is very Bond. Goff to rhyme with toff. Fleming, after all, was a golf-playing, bridge-playing stockbroker with a weekend cottage in St Margaret’s Bay. And huntin’, shootin’, fishin’, that ain’t Bond. Although Fleming was brought up amongst the Landed Gentry (if relatively Nouveau Landed Gentry), he left that sort of thing to his brother Peter— and Ian kinda rebelled. The Wavy Navy (RNVR) for Ian, not the Grenadier Guards. An annual Ford Thunderbird as opposed to a beaten-up, muddy Land Rover. A polka dot bow tie and short-sleeved shirts in dark blue. A rare book collection housed in shiny black clam-shell cases, with the Fleming crest, presumably a late 19th-century grant of arms. In gold.

And we need to discuss the Bond girls. At the very top of my all-time Bond Girl List is the desirable Tania Mallet, daughter of a millionaire car salesman and a Russian aristo (turned chorus girl), a Fleming-esque combo if ever there was. Forget the painted, desperate wannabes of Instagram, Tania Mallet's gorgeous. I mean, seriously gorgeous, in an understated sort of way; alas, departing the screen far, far too soon— following that unsavoury encounter with Oddjob's hat, a steel-tipped, square-topped bowler from Lock & Co. of 6, St James's Street, London, SW1 (Tel: 020 7930 8874), in case you were wondering.

In Fleming's novel of '59, Tilly Masterson's of the sapphic persuasion, which doesn't really come across in the film, although I suppose Tilly is a trifle bolshy, but then as Poossy Galore reminds Bond, she's 'immune' to his smarmy chat-up lines. And the brittle English girls with their cut-glass accents make a refreshing change from the "ow do you say' European dollybirds. I'm also assuming that Pussy's gels, the Wagnerian pilots of Pussy Galore's Circus, are of a similar inclination to their leader, as Venetia pointed out: “an English Public Schoolboy's fantasy come true.” Again, all this is very Fleming— but then take a peek at Ian and Annie's sex life. Nothing like a jolly good lashing before breakfast, eh? Vive Le Vice Anglais.

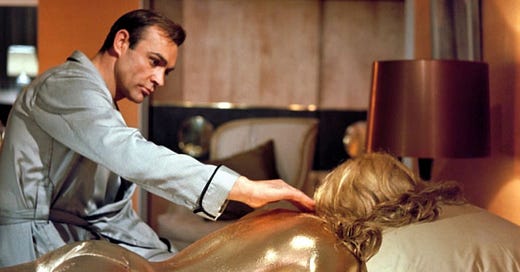

And gold, again, is very Fleming. The allure of which floats my boat, too, a sympathy I share with the Commander. Have it my way, and I'd get Britain back on the Gold Standard in a jiffy. I'm a hoarder. If I collected coins (which I don't), I would very much like a secret stash of gold Napoleons (in a wall safe, hidden behind a sub-Impressionist painting, beneath a picture light) to gloat over. Gold is fascinating. After all, when you think about it, it's a useless material with very little practical value— its value lies in its history, its emotional association, its imagined worth, almost impossible to quantify: a bit like the Mona Lisa, which, logically (if you're an accountant) should really only be worth the resale price of the canvas, paint and the bits of old wood which make up the frame. And poor Shirley Easton meets her demise via a tin of spray-on Dulux. As those of you of a kinky inclination may have already discovered— or so I have been told— you don't actually have to leave, I quote, 'a small bare patch (of skin) at the base of the spine' to breathe, as according to medical advice, we don't, actually, breathe through our skin. We breathe through our mouths.

By 1973, Bond is dead. Bond meets his metaphorical demise in Live and Let Die: the film's title could not be more prescient. Which may explain why Goldfinger, in its way, is the ultimate Bond. It catches the Cold War zeitgeist. There's an arched tongue-in-cheek irony, yet, at the same time, it's also weirdly serious. By 1973, Roger Moore's rent-a-quip, middle-aged Bond is seducing nineteen-year-old girls with a loaded Tarot pack— against a background of Watergate (almost), the oil crisis, natty safari suits and the occult.

We live in an age of political correctness on acid. Watching Goldfinger again last night, a finger-wagging Cromwellian warning for 'substance abuse' appeared at the beginning of the film. Can a clever reader please explain that one to me? What substance abuse? A Dry Martini? Shaken not Stirred? Because Fleming got it wrong; and it should be the other way around? Now that's substance abuse. Yet the Bond franchise, for some reason (an elusive cultural nut I have yet to crack), remains as popular as ever. Write a Bond post, and, inshallah, it will do well. But then perhaps a younger audience simply doesn't get it? The misogyny, the underlying hints of dark, masochistic sex; the violence, the drinking and smoking, the snobbery and the materialism, rich sauces over veal (that's a cute baby calf, folks), the appeal of the all-polluting internal combustion engine. After all, their Bond looks like somebody who's come to mend the washing machine. Or perhaps it's this voyeuristic 'web of sin' that explains the Bond phenomenon? Despite everything? The unacceptable face of the 1960s?

I watched Goldfinger (1964) via Amazon Prime Digital Download. As you might suspect, it’s also available in various Special Editions on DVD and Blu-ray.

You’ve just been reading a newsletter for both free and 'paid-for' subscribers. I hope you enjoyed it. Thank you to all those of you who have signed up so far.

There are two options on Luke Honey’s WEEKEND FLICKS. Cinema for Grown Ups: ‘Paid-for’ subscribers get an extra exclusive film recommendation every Friday morning, plus full access to the complete archive— which is currently at film no. 88, and should list over a hundred films by the end of the year. It costs £5 a month (or £50 a year)— a bargain, frankly, when you compare it to a few cups of coffee, a packet of semi-legal gaspers, or a pint of beer in the pub. ‘Free’ subscribers get access to the Sunday newsletter, plus the ‘free subscriber’ films in the archive. Either option is a good bet. And when I get my act together, I’m planning to add a spoken voiceover (mine!) for paid subscribers.

I will be back next Friday. In the meantime, I hope you have a relaxing, cinematic, and Dry Martini-fuelled Sunday. And Stirred not Shaken.

The American censors nearly spat the dummy at “Pussy Galore” (it wasn’t subtle, Ian) until Cubby Broccoli showed them the newspaper coverage of the Duke of Edinburgh and Honor Blackman under the headline “The Prince and the Pussy”. Oh well, if it’s by royal appointment, must be legit, and absolutely definitely not a single entendre.

All my family are keen golfists, member of Moor Park. My one rebellion was not taking up the game. My grandfather used to worry about me.