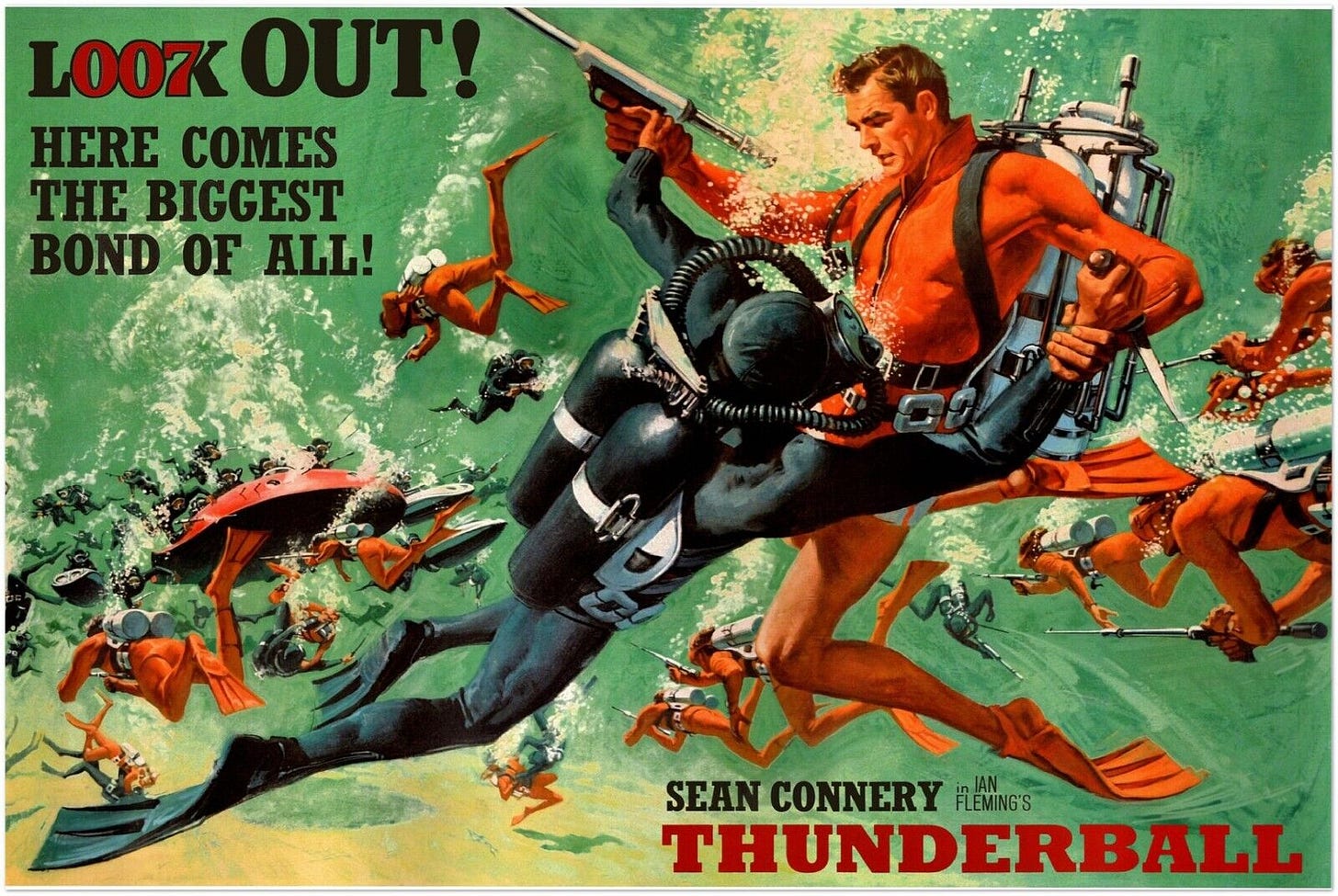

Thunderball (1965)

"See you later, irrigator..."

Thunderball (1965). Is it the quintessential Bond? A Bond blueprint? It’s all there, isn’t it? Perhaps even more so than Goldfinger (1964)? For by 1965, the Bond franchise was in its stride: a working synthesis between Ian Fleming’s literary creation and Eon’s cinematic Bondian vision: things nautical, girls in bikinis, sharks in suburban swimming pools, Caribbean tourism, carnivals, casinos and sadomasochistic health farms, brutal fights and stunning underwater cinematography; Connery’s toupée and the Aston Martin DB5. Fleming’s original novel, published by Jonathan Cape in 1961, is based on a (then) uncredited film script, hashed out by Fleming, his school friend Ivar Bryce, Irish film producer Kevin McClory, and scriptwriter, Jack Whittingham — subsequently landing Fleming in significant legal trouble when McClory accused Fleming of plagiarism. The case was eventually settled out of court in McClory’s favour. Fleming, already tired and ill, died of a heart attack in the summer of 1964.

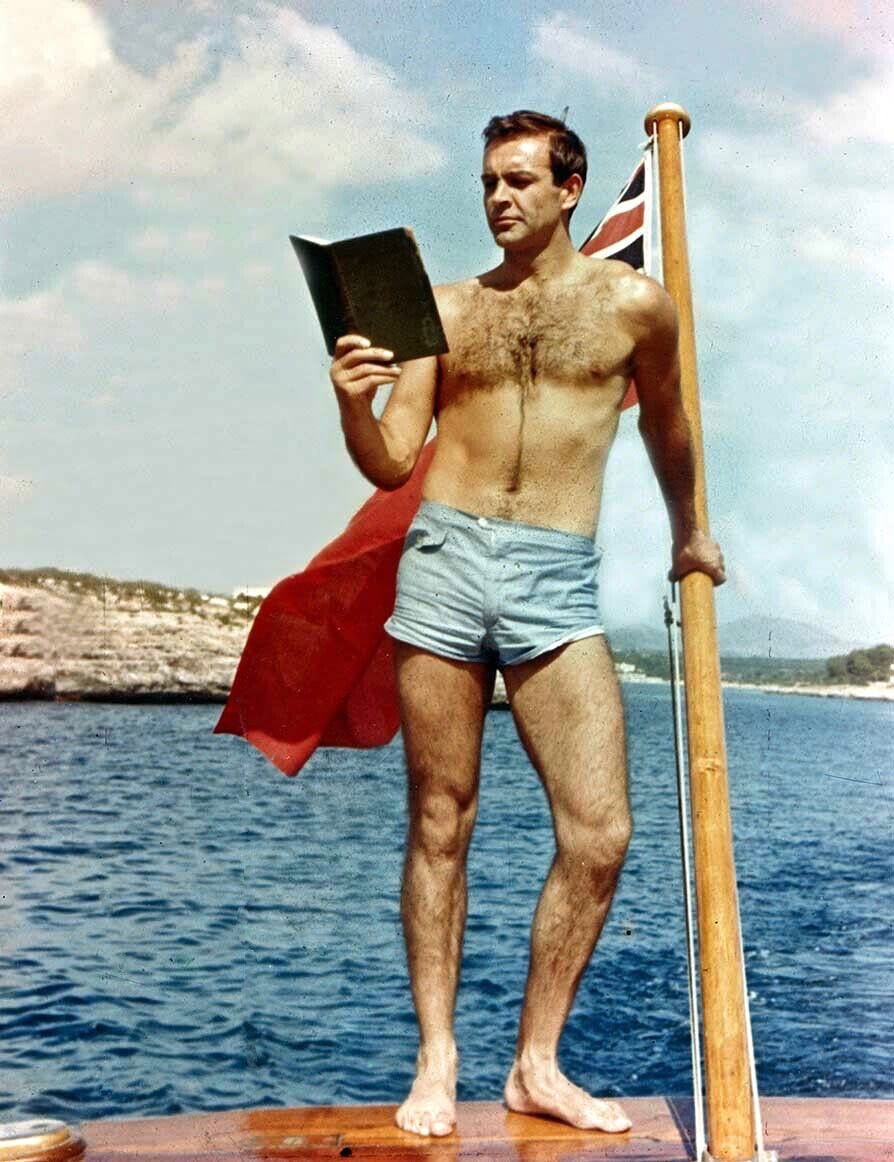

It was Terence Young’s third Bond, following Dr No (1962) and From Russia With Love (1963). And Blofeld’s second, albeit Blofeld's lower half and a furry white pussy cat. And Thunderball’s only hitch, perhaps, is Bond's brown suit. But we can overlook that. And Domino is a trifle passive. I sat down and watched the thing last night. From beginning to end. I liked it. If it lacks the panache of From Russia with Love (1963), the punch of Goldfinger (1964), the vulgarity of Diamonds are Forever (1971), the energy of Live and Let Die (1973), the tackiness of The Man with the Golden Gun(1975), or the sophistication of my all-time favourite Bond, On Her Majesty's Secret Service (1969), it is, at least, very much a film of its own time, of the mid 1960s — with its Cold War plot, its underwater cinematography, Sean’s chest wig and its misogyny. The brutal fight — at the beginning of the film — between Bond and Colonel Bouvard (presumably a Soviet agent in drag) is very Fleming. Unlike the later Bonds of the 70s, it's also strangely serious. By the 70s, times had changed. Vietnam, Watergate and the Oil Crisis saw to that. And Roger Moore’s Bond, a foil to an already outdated concept, survives (as much as I like him) on bar-room quips, on knowing ‘irony’, on cringe-worthy throwaway lines, on a smirk and a wink and a Union Jack parachute.

Bond aficionados — the lifestyle bloggers — adore Goldfinger (1964), often described as ‘the Bond with everything.’ It’s possible that the American setting (Kentucky) appeals (for obvious reasons) to a vast and influential American audience and the Thunderball setting — of British Colony and Home Counties health farm — doesn't hold the same attraction. But if Honor Blackman makes a terrific Pussy Galore, Goldfinger (Gert Fröbe) is more of an American corporate villain (remind you of anyone?) than a mastermind of international evil. That said, Thunderball’s Domino (Claudine Auger) is a little bit Eurotrash ("how d'you say?"), easily compliant, compared, say, to Honor’s feisty Pussy, Diana Rigg’s sophisticated Tracy in On Her Majesty's Secret Service (1969), or the brash Nevada scrubbers of Diamonds are Forever (1971).

For as I have said before, and don't mind saying again, Fleming’s patriotic Bond is very much a product of the 1950s and early 60s. When Britain still had an Empire — sort of — and when, in 1960, the Royal Navy could still field eight aircraft carriers. Unlike Goldfinger (1964), which is set partly in Switzerland and mainly in America, Thunderball is very much a British operation (with a brief interlude in Paris), based in The Bahamas, a British Crown Colony until 1973; and the CIA, rather gratifyingly, does what it's told, under British direction. M’s Whitehall conference room, supposedly an SIS set-up, is amusingly over-the-top, the ultimate power-office, courtesy of Ken Adam, like an outrageous Versailles or a marbled Saint Petersburg, with huge 17th-century tapestries and chandeliers and a horseshoe of William & Mary high-back chairs, along SPECTRE or United Nations lines.

At the same time, Shrublands, the Home Counties health farm, is a magnificent, Fleming-esque concept, where M sends a jaded Bond. Here he encounters a marvellously plummy Count Lippe, played by Guy Doleman of Colonel Ross fame:

‘This officer’, he read, ‘remains basically physically sound. Unfortunately his mode of life is not such as is likely to allow him to remain in this happy state. Despite many previous warnings, he admits to smoking sixty cigarettes a day. These are of a Balkan mixture with a higher nicotine content than the cheaper varieties. When not engaged upon strenuous duty, the officer's average daily consumption of alcohol is in the region of half a bottle of spirits of between sixty and seventy proof. On examination, there continues to be little definite sign of deterioration. The tongue is furred. The blood pressure a little raised at 160/90. The liver is not palpable…’

There was always a Puritan streak to Fleming, who came from Presbyterian Scottish crofter stock. Luxury was to be enjoyed but also deserved punishment. And there is nothing more masochistic than a ‘luxury’ health farm, a temple to denial, which, at the same time, costs an arm and a leg. Before we were married, I drove, with Venetia (in a Saab Turbo) across the Graveyard of Europe to Baden-Baden, a delightful stucco’d spa town, a Teutonic Cheltenham, in the state of Baden-Württemberg to the West of Germany, and it’s a fascinating place. Here, the European obese take courses in hydrotherapy and colonic irrigation: their backsides flushed with Badoit, pummelled into oblivion by white-coated devotees of the butch. Shrublands, I suppose, is a Fleming equivalent; it’s the perfect name for such an institution (taken from the Berkhamsted house of the parents of writer, Peter Quennell), conjuring up visions of smooth green lawns, suburban rhododendrons and a parked Silver Cloud. Fleming’s original novel, published in 1963, as ever, is very, very funny: peppered with his wry, bone-dry humour, sometimes so dry, it's barely discernible:

Bond walked out and along the white painted corridor. People were sitting about, reading or talking in soft tones in the public rooms. They were all elderly, middle-class people, mostly women, many of whom wore unattractive quilted dressing gowns. The warm, close air and the frumpish women gave Bond claustrophobia. He walked through the hall to the main door and let himself out into the wonderful fresh air.

And Thunderball’s maritime battle is truly something — but most probably needs to be viewed on the big screen. Despite the clear waters of Clifton Pier in Nassau Harbour, it looks a trifle murky on a small television set. But scuba diving was hot. By the 1960s, Jacques Cousteau (a Fleming hero) had pioneered underwater filmmaking, developing specialised cameras and underwater lighting (The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau [1968]). There was always something rather Bond about Captain Cousteau, from the urbane leather-lined study in Monaco to his underwater base, like the lair of a Bond villain. And, yes, I'm sorry, folks, but sharks were indeed harmed in the making of Thunderball. For it’s the underwater scenes you remember — and that's how it should be. Things nautical — like the Austrian or Swiss Alps — are what Fleming’s all about. Square riggers, sunken treasure, desert islands, pirate maps, pieces of eight, bottles of rum. Jamaica, the Bahamas, British Hong Kong, Japan, and Zurich — these are Bondian places. India is not.

I watched Thunderball (1965) on Amazon Prime Video Digital Download. There are, of course, all sorts of tempting editions on DVD and Blu-ray which include additional goodies and extras. I’m working on my Bond DVD collection: there are notable gaps when it comes to Brosnan and Craig, which may well remain notable gaps.

Thunderball is Film No 115 in the official WEEKEND FLICKS. archive. There are two options on Luke Honey’s WEEKEND FLICKS. Cinema for Grown Ups: ‘Paid-for’ subscribers get an extra exclusive film recommendation every Friday morning, plus full access to the complete archive.

It costs £5 a month (or £50 a year) — a bargain, frankly, when you compare it to a few cups of coffee, a packet of semi-legal gaspers, or a pint of beer in the pub. ‘Free’ subscribers get access to the Sunday newsletter, plus the ‘free subscriber’ films in the archive. Either option is a good bet. And when I get my act together, I’m planning to add a spoken voiceover (mine) for paid subscribers. I hope you enjoy Thunderball as much as I did. A Dry Martini for this one. And stirred, not shaken, s’il vous plaȋt. Mister Bond, alas, needs instruction. See you Friday. Ciao.

The death of Fiona to the tune of ‘Mr Kiss Kiss Bang Bang’ is such an excellent set piece. And the Avro Vulcan is one of the film’s silent stars, a thrilling piece of British hardware, though sadly ill-fated.

Anyway, yes, an underrated Bond. Not as zippy as some but with much else to commend it. The thing that always bothers me about ‘Goldfinger’ is that most of the ‘iconic’ (sorry) moments occur in the first half, while Bond spends much of the second somewhat ineffectually locked up. But don’t get me started.

Though she’s not a major Bond girl, in the sense of screen time, Molly Peters made a very, very big impression on me at an impressionable stage of my life!

And she was the first Bond girl to be shown naked, albeit from the back and through an appropriately steamed-up window, which I’ll happily always remember her for.

Watched it again recently, and was pleasantly surprised by the pre-title fight sequence…it is pretty violent, isn’t it? And, of course, the unforgettable jet pack, and the Vulcan sequence, which were just manna from heaven for boys of a certain vintage and bent. A different manna, though, than the one dispensed by Molly, of course!

Was Connery already bewigged by the time of Thunderball, Luke? If so, they did a good job keeping it attached for all those underwater sequences, no!?