When I survey this work as a whole I find I have drawn a picture of a vanished age. The character of society, the foundations of politics, the methods of war, the outlook of youth, the scale of values, are all changed, and changed to an extent I should not have believed possible in so short a space without any violent domestic revolution.

From the Preface, My Early Life: A Roving Commission by Winston Churchill O.M., C.H., M.P. (1930).

Despite my obsession with all things historical, the epic historical biopic, alas, usually leaves me a little bit cold. Fans of Cromwell (1970), Gandhi (1982), Chaplin (1992), Braveheart (1995), Nixon (1995), Lincoln (2012), Jackie (2016) and Daytime Believers: The Monkees Story (2000) will await in vain for a recommendation to appear on these pages. I'm aware of how arrogant (and high-handed!) this must seem; to dismiss a popular genre in its entirety — but I trust you will forgive me for that. As I said from the beginning, this Substack is very much a personal view — a bit like a film diary, which, I hope, might inspire you to watch (or rewatch) a film that you might not have otherwise considered. Call it serendipity.

Biopics (especially the made-for-television variety), and again, I am aware this is a generalisation, tend, I find, to be rather formulaic in approach, and that can be a trifle dull. And there’s also the sense of history — a difficult thing to get right. Especially with all the endless complications and budget constraints involved in actually making a film. Persuading a sophisticated and increasingly cynical audience that a film really is taking place in 1888, 1923 or 1969: in foggy Victorian London, gangster Chicago or hippy, psychedelic San Francisco, as opposed to the backlot of Pinewood or Universal Studios. It’s not just about historical anachronisms, it’s more about a sense of place: I’m never especially fussed by anachronisms, actually, thinking about it, I rather enjoy them: Glenda Jackson’s Olde Tudor radiator in the BBC’s Elizabeth R (1971), the Luftwaffe helicopter in Where Eagles Dare (1968), the double yellow lines in Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979) and, at the Duchess of Richmond’s ball, the Gordon Highlanders’ plastic bagpipes in Waterloo (1970) — although, admittedly, the officers’ First World War uniforms in Downton Abbey (2011) gave me sleepless nights — pips on the shoulder strap rather than sleeve? In 1916? What is the world coming to?

Which takes us to Richard Attenborough’s Young Winston (1972) (written and produced by Carl Foreman), which, I suppose, one might describe as a biopic — but a biopic with a difference. It’s a wonderful film. But before we continue, a quick but necessary plug for the art of the film title (i.e. the introduction to a film), an art rarely commented on and sometimes, and quite often, more interesting than the film itself. Young Winston (1972) opens with a shot of the library at Chartwell, set against Alfred Ralston’s poignant score, with title design by the brilliant Maurice Binder, also responsible for the titles of 16 Bond films. I love the appropriate Art Nouveau font (so fashionable in 1972!), reminding me of a similar set up in Lionel Jeffries’ masterpiece, The Railway Children (1970), which we revisited last Christmas. Films of the early 70s are so often beautifully made and put together. And then there’s that very English thing, too, a subtle nuance, which in the right hands translates well to film. Poignancy. A poignancy for the Late Victorian and Edwardian Golden Age. An age which most probably never existed (in truth, the Edwardian era was an age of strikes, unrest and rapid social change), but seen from the context of two World Wars, appears like a vanished Valhalla — especially from the point of view of the 1970s.

And the cast! Oh, the superb cast! The casting director deserves a medal. Simon Ward is Young Winston Churchill. Robert Shaw is Lord Randolph. Anne Bancroft is Jennie, Lady Randolph (“more of the panther than of the woman in her look”). Hopkins is “that odious little man, Lloyd George”. And then we have Robert Hardy’s deeply unsavoury and sycophantic prep school headmaster (note the seedy black finger strap, presumably the bi-product of numerous canings, a lovely detail), and a terrific supporting cast: John Mills (as Lord Kitchener), Ian Holm (as George Earl Buckle, editor of The Times), Jack Hawkins (as the headmaster of Harrow), Robert Flemyng and Edward Woodward. And Jeremy Child as a young Austen Chamberlain, and Jane Seymour as the lovely Pamela Plowden, Winston’s first crush. And, somehow, they managed to find a teenage boy (Michael Audreson), Simon Ward’s younger doppelganger, for the sequence filmed at the Speech Room at Harrow.

Young Winston is based on Churchill’s My Early Life: A Roving Commission, published in 1930. It’s a charming book — beautifully written — and if you haven’t read any of Churchill’s books, it might be a very good place to start. For Churchill paints a ‘picture of a vanished age’. He liked to play up his supposedly unpromising youth, the underwhelming school days at Harrow, his failure to get into the 60th Rifles, a distinguished but more affordable option than the expensive and glamorous 4th (Queen’s Own) Hussars, when, actually, Winston was the Public School Fencing Champion for All England, excelled at History and English, and although it took him three attempts to get into Sandhurst, eventually finished 20th in his class, out of 130 cadets.

In preparation for this post, I had a quick peek at the comments on various internet forums (Young Winston holds an uninspiring 55% rating on Rotten Tomatoes). Some of the commentators struggled with the off-screen voice of the bitchy and sarcastic journalist (as if from The London Illustrated News or similar journal), a device used by Attenborough to ‘interview’ Lord and Lady Randolph and the twenty-six-year-old Winston, finding this ‘creaky’, or similar words to that effect — an approach, personally, I find more than effective and like very much indeed. There were further complaints about the battle scenes, which some reviewers found, surprisingly, unconvincing. I don’t get this. Winston’s cavalry charge with the 21st Lancers at Omdurman — the last major cavalry charge of the British Army — is terrific. And the battle with the armoured car during the Second Boer War. Just before Winston is captured. These are the things that you remember. Or, at least, I do. Is this an audience brought up on the dreaded CGI? An audience expecting a plethora of fast-moving graphics? Like a computer game? Thrills, Spills, and Big Bang Surround Sound?

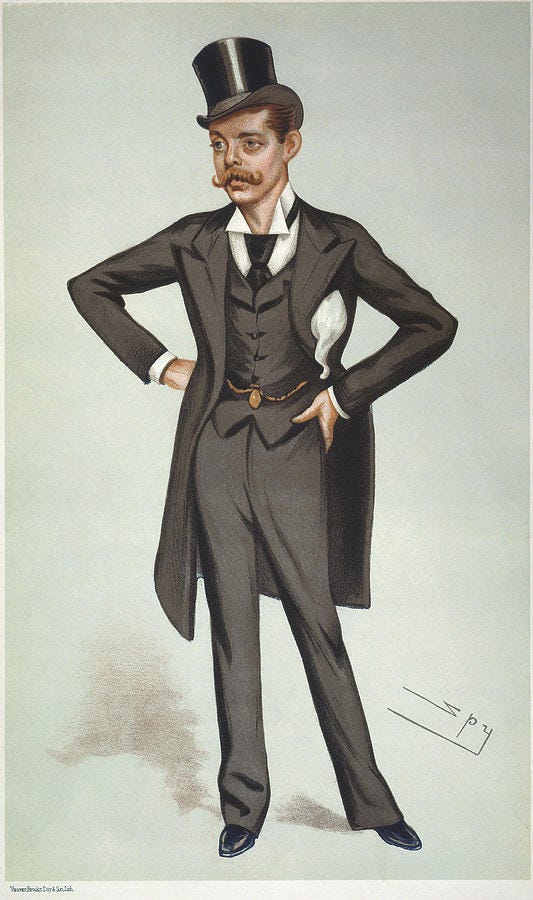

But the two standouts in this film are, without any doubt, Robert Shaw’s superb performance as Lord Randolph Churchill and Anne Bancroft as Winston’s American mother, Jennie, Lady Randolph: ‘She shone for me like the Evening Star. I loved her dearly — but at a distance.’ Even by the standards of their day, Lord and Lady Randolph were neglectful parents. Winston had a difficult relationship with his father. Lord Randolph is a fascinating and ultimately tragic figure. A brilliant man with a ‘strange meteoric career’, a ‘progressive Conservative’, a promoter of the Primrose League and a stylish advocate of Disraelian One Nation Conservatism and Tory Democracy. A man who threw everything away — a tactical resignation, all in the relatively minor cause of cuts to the defence budget. A gamble which didn’t pay off. The Prime Minister, Lord Salisbury, accepted Lord Randolph’s resignation, effectively ending what had been, until then, a brilliant career. Winston hero-worshipped his father: he dressed like Lord Randolph (the black and white polka dot bow tie): Winston’s whole raison d’etre revolved around a desire to prove to his father his worth: he even died on the anniversary of his father’s death — January 24th:

“All my dreams of comradeship with him, of entering Parliament at his side and in his support, were ended. There remained for me only to pursue his aims and vindicate his memory.”

Attenborough originally filmed a sequence with the older Winston (set to Elgar’s Nimrod) asleep in his studio at Chartwell, talking — in the Never-Never Land of Somnia — to the ghost of his still critical father, played by Robert Shaw. This is based on The Dream, a haunting short story Winston wrote in 1947 and never published during his lifetime:

“I never brought you up to anything. I was not going to talk politics with a boy like you ever. Bottom of the school! Never passed any examinations, except into the Cavalry! Wrote me stilted letters. I could not see how you would make your living on the little I could leave you and Jack, and that only after your mother. I once thought of the Bar for you but you were not clever enough. Then I thought you might go to South Africa. But of course you were very young, and I loved you dearly. Old people are always very impatient with young ones. Fathers always expect their sons to have their virtues without their faults.”

I managed to find this sequence online, and you can view it via a Robert Shaw Tribute website. It’s deeply moving, especially as Winston hides his fame and achievements: Randolph assumes that Winston is some kind of book-dealing dilettanti. There you go, that subtle nuance (that English poignancy) I mentioned earlier on in the piece. As moving as it is, though, it’s understandable why Attenborough ditched it. It sort of jars with the rest of the film, and visually, looks a little bit awkward.

Randolph, famously, died of syphilis. Or so it is thought. In any event, there was an unpleasant degeneration of the brain, a mysterious ‘general paralysis of the insane’, as it was then described, caused (as they thought) by overwork and exhaustion, leaving violent mood swings: from grandiose delusions to extreme rage and paranoia, slurred articulation, the loss of movement to arms and legs, leading to inevitable death, a condition which most historians now identify as tertiary syphilis, although an alternative theory suggests that Randolph died of a brain tumour. It’s worth reading up on. There’s an interesting interview with Robert Shaw on the very subject via the excellent Dick Cavett Show.

So there you go. Young Winston (1972). It’s a weepie. I hope I’ve written enough to persuade you down that metaphorical rabbit hole. Incidentally, as an antique dealer — and a writer specialising in art and antiques — I’m always interested in the promotional nick-nacks which accompanied the release of a film. The books, toys and records. The promotional tie-ins. Lone Star cap guns even brought out a toy ‘Young Mr. Churchill 7.63mm Broom Handle Mauser’, a 100 shot Cap Repeater with ‘Flip Loading Magazine’, a ‘replica of the Mauser pistol which he carried while reporting the Boer War’. Oh, how I would have loved to have woken up to that one on a frosty Christmas morning! It’s now a collector’s item if you can find one in the original packing. EMI also brought out The Edward Elgar Collection inspired by Young Winston which featured Simon Ward and Jane Seymour — in their Late Victorian finery — on the LP sleeve.

I watched Young Winston (1972) on Amazon Prime Digital Download, and it’s also available on DVD and Blu-ray. Before I go, a quick word about the paid subscription, which costs £5 a month or £50 a year. Paid subscribers get their own special post on Friday mornings, extra bonus posts on High Days and Holidays, and access to the entire archive — which is now running at some 134 films. Sunday morning’s post is free, and can be read by everybody and anybody. Many, many more films to come... Subscription button below.

Another lovely visit back to the Levenshulme Palace for a Saturday afternoon matinee, Luke. And who could argue with 25 new pence for a ticket and a choc ice?

Terrific stuff, as ever, Luke!

Yea, verily, an unbeatable cast, and a potentially str-making role for Simon Ward that never truly materialised, which is a shame. Have you seen I Start Counting (1970), Luke? He puts in a convincingly sinister and disturbing performance, but not one, alas, that helps build the image of a clean cut and golden tressed film star.

And Maurice Binder never made a duff set of film titles, did he? I always thought then, and still do, that if I watch a film that opens with his titles then that film will be a good ‘un. Not always true, of course, but his titles were always worth the price of admission.

Thanks again, Luke, for this reminder to go back and watch again…which, thus far, you’ve not yet disappointed with your choices, and I doubt this one will, either.

Reading your posts I’m struck by the sheer number of films I went to see in the 70s and 80s. I must have spent half my life in a theatre… What I remember most about the film are the South African scenes, and yes, compared to the often stilted and pompous historical bios, this one stands out, fresh, not hagiographic.