A Bonus Post for Easter:

The village of Penn lies on a Buckinghamshire ridge, about thirty miles to the northwest of London. On fine summer days, from the Medieval church, one can see Windsor Castle, a grey smudge on the plain of blue haze which is the Thames Valley. Penn is an interesting village with its share of distinguished former residents: the poet Walter de la Mare, the novelist Elizabeth Taylor, Sunday Express columnist Veronica Papworth, and Grande Dame of British cookery Mary Berry. Until recently, there was a charming and eccentric second-hand bookshop staffed by two little old ladies. And to the literary mix, we must add a coterie of amateur racing drivers: Len and Bluebelle Gibbs, the proprietors of Slade’s Garage; Lord Curzon, later Earl Howe (winner of the 1931 Le Mans and President of the British Racing Drivers Club); Anthony Heal (chairman of the famous London furniture department store), Humphrey Wyndham Cook (a racing driver of the 1930s), and Cook’s stepson, the failed hotelier, aspiring racing driver and motor engineer, David Blakely.

On Easter Sunday, 1955, Blakely met his demise at the hands of his on-off girlfriend, Ruth Ellis, gunned down with a .38 Smith & Wesson revolver outside the Magdala pub in Hampstead. Tried for murder at the Old Bailey, Ruth Ellis — the mother of two —was the last woman to be executed (a date with the noose, that most Victorian and macabre of executions) in Britain, despite considerable public protest and sympathy. David Blakely is buried in the graveyard of the Holy Trinity Church, Penn. His gravestone bears the insignia of his former regiment, the Highland Light Infantry.

Slade’s Garage is still there, quite close to the village duck pond, and looks very much the same as it did in the 1950s, with its painted woodwork in Slazenger Green and fascia in a swirling, vaguely 20s or 30s script: Service… Sales… Austin… Morris & MG. It is now a specialised dealership in exotic and valuable classic cars. And it is at this point that I must admit to having more than a passing interest in Penn. For in 1950, my grandfather bought the ancient Parsonage Farm nearby — a wonderful, late 16th-century house of brick-and-timber, with moat, barns and a raised granary on stilts, which my grandmother claimed, most improbably, to have been mentioned in the Domesday Book. I checked. It isn’t. Or wasn’t. But it was here, in a vast, tarred and dusty 18th century Buckinghamshire barn, that my grandfather kept his beloved cars, his Lancias, Mercedes-Benzes, Alfa Romeos and Riley Roadster. I only mention this in passing to give you a flavour of the place and its times — for as late as the 80s, one might drive up to the forecourt of Slade’s (in my case, in a rusted Renault) and old Len would come out for a chat and fill up your car — billed to my grandfather’s account— from an old-fashioned petrol pump, topped, no doubt, with the Shell scallop in moulded celluloid. It’s a vanished world.

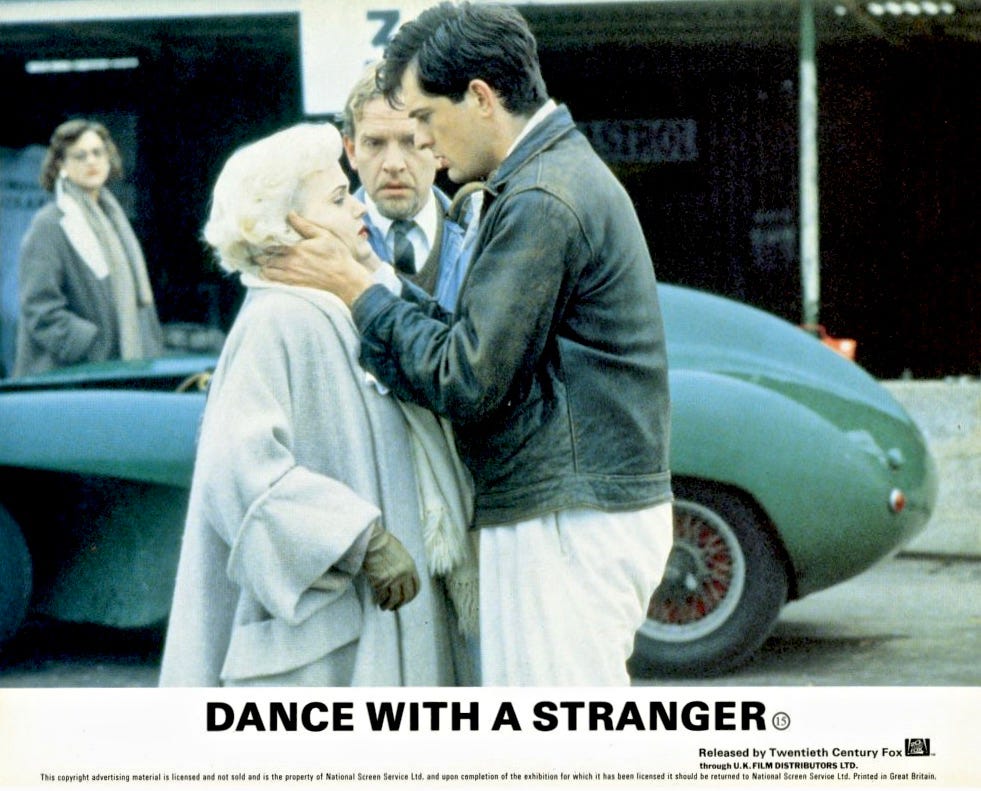

In the film-noirish Dance with a Stranger (1985), directed by Mike Newall, this Betjeman-esque world of the brick-and-flint Home Counties, of tweeds, Liberty headscarves, gymkhanas and MGs, collides with the seediness of London in the 50s, a world of shilling-in-the-slot gas metres, call girls and The Steering Wheel Club, the world of Stephen Ward, Christine Keeler, and Notting Hill property developer, Peter Rachman. It’s also Patrick Hamilton territory. In The West Pier (1951) everything is bogus. Ralph Gorse’s Old Westminster tie; Ye Olde Wheatsheaf, with its ‘viley restored Elizabethan architecture’ and the elderly Anglo-Indian residents in the ‘long, low beamed room.’ And into this Home Counties Nirvana, of bridge, coffee-mornings and string-backed driving gloves, poor Ruth Ellis, the nightclub ‘hostess’ did not fit.

In a rapidly changing Britain, I’m haunted by the past. Despite the survival of Slade’s Garage, the Cottage Bookshop is no more, now a ‘private residence’, as is the former butcher’s shop, next door. Until the 90s, stood an old-fashioned grocer almost directly opposite, like the shop in Beatrix Potter’s Ginger & Pickles, with moted bow window and serried glass jars of radioactive gobstobbers, staffed by an old dear in a blue nylon housecoat, which, again, has fallen to the rising value of residential property. On the Beaconsfield road, the fine old Edwardian houses are being demolished one-by-one to make way for the vast tarmacadamed piles of the super-rich, complete with gymnasiums, indoor swimming pools and private cinemas. But on the A40, at Gerrards Cross, the Bull Hotel (a late 17th century coaching inn and former haunt of highwaymen and other nefarious gentlemen of the road) still plies its trade — once a regular stop-off for David, Ruth and Jaguar XK120 (in Old English White, or at least, according to Dance with a Stranger) on the way back to London. Do the ghosts of the past still linger? Where today, the bloated, angry SUVs hurry past on the road to nowhere? A phantom world: of warm gin and tonic and a limp slice of lemon? The imagined stained oak beams, brasses and plum carpet of the Jack Shrimpton Bar?

Dance with a Stranger (1985) may well be up there in my top-ten British films, and most certainly my top-twenty. For the early to mid 80s was a time for creative independent film-making in Britain. Thank you Goldcrest and Film Four International. Films of intelligence, subtlety and understatement; often visually aesthetic with beautifully written scripts — despite the relative brashness of that ‘loads of money’ decade. The names of these films trip off your tongue, like a glorious index: The Elephant Man (1980), The Long Good Friday (1980), Chariots of Fire (1981), Gregory’s Girl (1981), Local Hero (1983), The Draughtsman’s Contract (1982), The Return of the Soldier (1982), Dreamchild (1985), Another Country (1984), A Company of Wolves (1984) and Room with a View (1985). Mike Newall went on to direct Four Weddings and a Funeral (1994) — by far the best of the Richard Curtis stable.

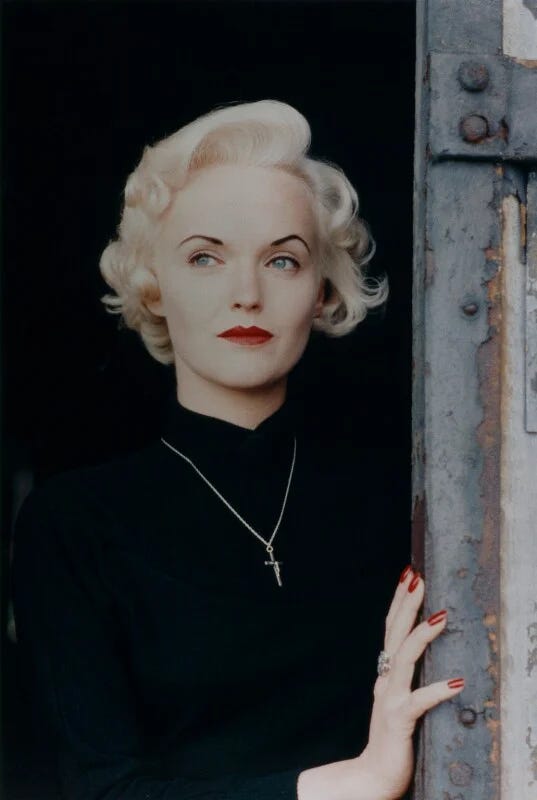

Dance with a Stranger (1985) is a superb film — it’s as simple as that. A notorious, desperately sad, real-life tragedy requires a subtle interpretation with sensitive casting and a tight script. Scriptwriter Shelagh Delaney nails it, as does Miranda Richardson. She’s great, is Miranda. Fans of Anthony Powell’s Dance to a Music of Time will remember her brilliant Pamela Widmerpool in the excellent television adaptation of 1997. Exactly as I imagined from Powell’s novels. And underneath that brittle, chiselled 50s perfection, there’s Miranda Richardson’s Ruth Ellis: an ersatz, English, suburban Marilyn Monroe, hiding beneath a facade of caked makeup, platinum hairdo and affected, over-refined accent: a vulnerable and ultimately damaged young woman, living a precarious existence on the financial edge — or as Vanessa McQuarrie on the BFI Screenonline website puts it:

Much is made of Ellis's inability to see - she constantly needs to put her glasses on, but refuses, out of vanity, to wear them all them around. Her blindness is a metaphor for her desire, which masks the reality of her situation.

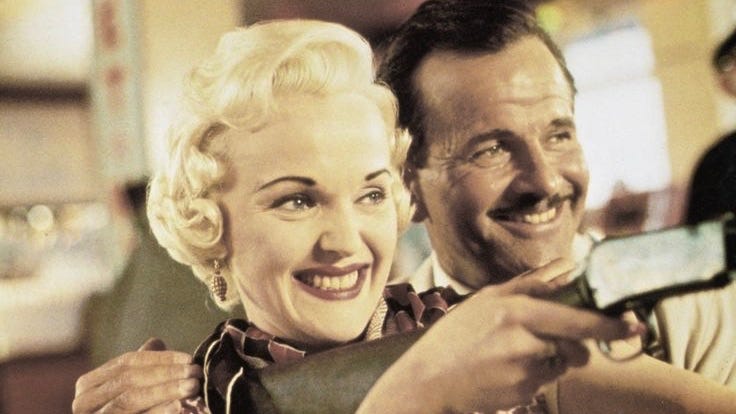

Rupert Everett is an equally inspired casting choice: David Blakely’s fortunate, comfortable, monied, upper middle class-ish background: Shrewsbury (‘shrew’ to rhyme with ‘crow’) and a National Service commission in the Highland Light Infantry (David Niven’s smartish regiment, sort of), descending into hard drink and violent abuse, “I keep hoping that you will change but you never do…” so that in January 1955, following yet another argument, Ruth suffered a miscarriage after David hit her in the stomach. The whole thing (the real-life ‘backstory’, as our contemporary TikTokers might put it) is truly awful. But, oh, this cast is good. I’m taken with Ian Holm’s Desmond Cusson, Ruth’s jealous boyfriend — a former RAF pilot (a debonair moustache, David Niven again) and ‘Company Director’ — that enigmatic job description which covers a multitude of sins. Ian Holm has (or had) to be one of our finest actors. His range is phenomenal. The way he reloads his pea-shooter on the Brighton fairground rifle range — so typical of any ex-serviceman of the 1950s. Now, that’s acting.

There’s also a wonderful sequence where David and Ruth drive out to Buckinghamshire to introduce Ruth to his parents. The large Georgian house is Culham Court, near Henley — actually a little bit grander than Old Park, Blakely’s family house in Penn: yet another Arts & Crafts number to have met its maker via chain and wrecking ball. And the village, where David and Ruth stop off for a gin and something, is the brick-and-flint confection of Hambledon — another inspired choice, lying as it does in a snug Chiltern valley, only a few miles from Penn. The long shot of the damp Turville valley and the evocative sound of the Jaguar’s Straight-Six, set against Michael Storey’s elegiac soundtrack (of saxophone and electronica), leaves me — literally — with a shiver up my spine. If I had to live abroad, watching this sequence would make me very homesick indeed. It has something about it. Haunting. But then I have a thing about the English countryside on a raw March morning. In Southern England, it very rarely snows. Instead, in Winter and Early Spring, mist rises off subdued, sometimes frosty, unsaturated fields. And then just what is it about early 80s film music? And, thinking about it, what is it about early 80s British cinema?

I watched Dance with a Stranger (1985) on an ancient DVD (I’ve had for years), having spent half an hour tearing my hair out trying to find it. In the meantime, I tried to download it via Amazon Prime Video — without success. This I find curious. Are there copyright issues? You can also find the complete film on various, slightly dodgy social media channels, with slightly dodgy video quality — I suspect far too blurry for a sophisticated, intelligent and discriminating audience, i.e. the readers of WEEKEND FLICKS. Cinema for Grown Ups.

You’ve just been reading a special Bonus Post for the Easter Holiday, which, I hope, will inspire you to track down a DVD of Dance with a Stranger (1985). Oh, how I love the Easter Weekend! The weather’s fresh, there’s far less hassle (and emotional baggage) than the forced extravaganza which is Christmas, and there are splendidly tacky chocolate Easter Eggs, with cheerful and brightly coloured packaging, which don’t cost an arm and a leg. My late grandmother used to treat Easter almost as if it was Christmas: modest presents distributed amongst friends and family (a wrapped Penguin paperback, or so); there was a huge, bronzed Turkey, decorations of daffodils, hyacinths and cute yellow chicks. And in her Rose Garden, there was an Easter Egg hunt for the kiddywinks. With Cadbury’s Creme Eggs, no less, to smear down the front of the Laura Ashley dresses.

Until recently, the BBC and ITV used to show a much-loved film on the Easter Bank Holiday Monday. Something like The Eagle Has Landed (1976) or Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (1968). Does this still happen? Alternatively, there’s now WEEKEND FLICKS. So here’s a quick word about the paid subscription, which costs £5 a month or £50 a year. Paid subscribers get their own special post on Friday mornings, special additional posts (when I can and please bear with me on that), and access to the entire archive — now running at some 137 films. The Sunday morning posts are free and can be read by anybody and everybody. I’ll be back on Good Friday with a post for the Paid Subscribers. Not sure yet what that will be, but I have one or two ideas up my sleeve. A period gem from the 1980s, perhaps?

I remember watching this the week it came out in the local cinema. The atmosphere brought to life was perfect, so was every little detail. Because aesthetics count in films, no matter what anyone says today.

The recent mini series did not even come close.

Miranda R's finest hour (and a half)