I've been hanging out with various riff-raff

Somewhere on the Goldhawk RoadLove is a Bourgeois Concept, The Pet Shop Boys (2013).

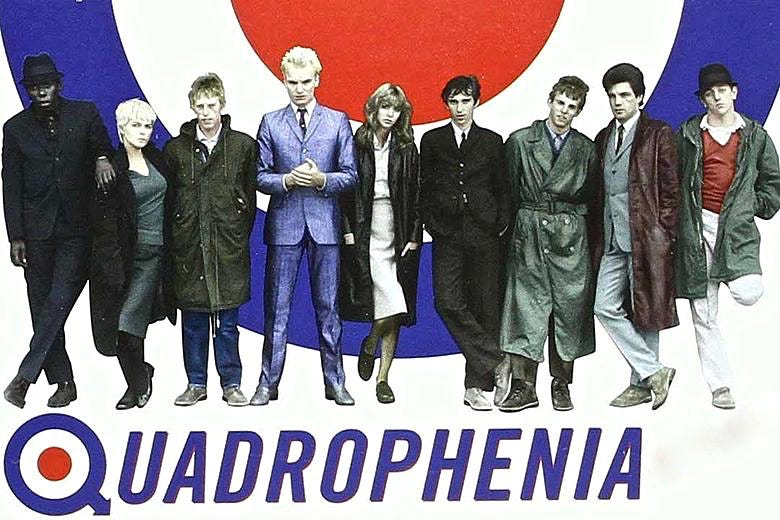

Jimmy Cooper (Phil Daniels) reminds me of Holden Caulfield in J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye (1953). Everyone’s a phoney: Ace Face (Sting), his girlfriend, Steph (Leslie Ash); the traitorous Dave (Mark Wingett), the drug-pushing gangster, Harry North (John Bindon)— and at the office, Mr. Fulford (Benjamin Whitrow) and the smooth-talking, corporate advertising exec played by Jeremy Child.

Like Up the Junction (1968), Franc Roddam’s Quadrophenia (1979) is a film about London’s working-class culture. Both films are set around the same time, give or take a few years— if, in the case of Quadrophenia (1979), it’s more 1964 going on 1979. How old is Jimmy? Nineteen? And an adolescent nineteen at that. Late adolescence is pretty nihilistic when you think about it. Limited. An intense, self-contained, self-obsessed world. A time when, on paper, you can vote, have sex, smoke and get married— and yet you have nothing: and despite all the angst, from a grown-up point of view, a relatively simple existence when compared to the complexity of adult life— and all that comes with it: you’ve got your tiny childhood bedroom, with its pin-ups; your bike (motorised or otherwise), some sort of boring, entry-level job (hopefully) and with luck a girl, or, at least, a girl you’re crazy about— and admire from afar. And unless you’re doing further education, that’s about it.

Supposedly set in the Shepherd's Bush of 1964, Quadrophenia's a fun-fest of charming anachronisms, even if some of them can leave you scratching your head. Renault 5s and 70s Cortinas in the Goldhawk Road? In 1964? On a limited budget, hiring a flotilla of period cars at five o'clock in the morning ain't feasible, I get that. But the shot of Jimmy's bedroom with a passing High-Speed InterCity 125 train in the distance— the pride of British Rail of 1975— leaves me perplexed. Surely, the director could have shot the scene sans train, low budget or no? When Quadrophenia hit the screens in 1979, these anachronisms seemed glaringly obvious, but today, with time, they seem to blur into one, a period minestrone: '64 and '79 now seem relatively close. In any event, I like anachronisms, which can give a film an edge. They also add to the charm— like a decent Burgundy, improving over time. The film itself encouraged a Mod revival in the late 70s and early 80s (or was this more a case of the chicken and egg?); '79 saw gangs of Mods and Rockers fight it out in the spas and seaside towns, including the genteel streets of shabby Cheltenham, then a land of peeling stucco, retired Colonels and Tarot Card Readers.

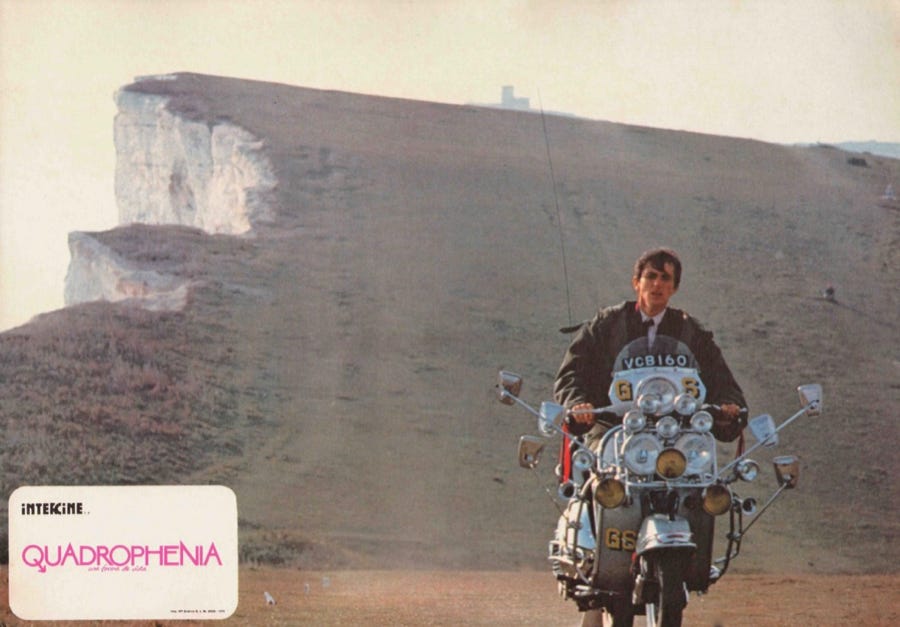

And Quadrophenia is, I think, very much a film in that poignant Rites of Passage genre. Strangely, not unlike The Go-Between, or Donna Tartt's The Secret History (1992), Alain-Fournier's Le Grand Meaulnes (1913) or Françoise Sagan's Bonjour Tristesse (1954). It’s a film about growing up. The ending, in which Jimmy nicks Ace Face's flash Lambretta and drives off Beachy Head— those towering, suicidal chalk cliffs near Eastbourne (filmed, incidentally, in a rather beautiful sequence)— strikes me as clear as the crystal waters of the English Channel. Jimmy survives. It's the ultimate rebellion. But, this time, it's a rebellion against himself. A rejection of Mod culture. That key moment when Jimmy discovers his hero, Ace Face (Sting)— the King of the Mods and a symbol of everything he looks up to— at the Grand Hotel, Brighton, dressed as a lowly bellboy. In an overtight, dinky little uniform with a ridiculous pill-box hat— just like Buttons. One of those dubious older types (he's twenty-seven) who hangs out with a younger crowd to give them an easy status. A loser. In a sense, Jimmy has a great awakening. His future's grim, sure. But it suddenly dawns on him that there's more to life than a Parker, a scooter, a Fred Perry polo shirt and a pork pie hat. There's hope.

In those days the Brighton police wore spiked white helmets; during the summer. And it's the seaside bits you remember in Quadrophenia: the fights on the Brighton seafront, beautifully choreographed and photographed, with movement and realism, and the shagging sequence in Quadrophenia Alley (11, East Street), a spot re-christened by persuasive film nerds and their girlfriends in their thousands, and the helicopter shots of the Oh- So- English white cliffs. It strikes me that cult films (and we can add Quadrophenia to a distinguished list) have a sense of place. In Blow-Up (1966), it's Maryon Park you remember, with its luminous grass and rustling trees; in WithNail & I (1987), it's Uncle Monty's shabby-genteel cottage in the Lake District; in If…. (1968), it's the black and white transport cafe (Sarson's Malt and H. P. Sauce) on the Tewkesbury Road, actually Bedfordshire— and in Straw Dogs (1971), a film we will be covering at a later point, it's the bleak Cornish landscape of St Buryan.

I've also realised that I've managed to get this far without mentioning The Who, which is kinda nuts. Quadrophenia (1979) is, of course, based on The Who's concept album of 1973, and scattered throughout are constant, almost subliminal references to the band and their personnel— actually not unlike a 1950s sneaky product placement for orange juice. But listening to the beautiful Cut My Hair, one of my all-time favourite tracks, makes you realise just how good The Who are. Compared, say, to the soundtrack of Up the Junction (1968)— and this isn't meant as a criticism— by the likeable pop-sensation, Manfred Mann. And, aside from their brilliance, I've a personal soft spot for The Who, as our mini-skirted Czech au pair girl (this was back in the late 60s when I was tiny) became an official Who dollybird, picked up by one of the boys one happy, sunny Saturday morning in Carnaby Street.

What else? Look out for John Bindon, the real-life gangster turned thespian, in the bit when Jimmy tries to buy a 'box of blues’ in the boxing club. Bindon was an interesting, if dubious, London character, rumoured to have dined à deux with Princess Margaret at the infamous Gasworks restaurant in Fulham— an institution where eccentricity became a creed, where Edward Gorey met the Hammer House of Horror, and a former haunt of the porters employed at the (former) Bonhams saleroom in the grotty, fag-end of The King's Road. I held my 30th birthday party there. At The Gasworks, not Bonhams. And somehow, The Gasworks has come to represent a London, now lost. But that story, perhaps, is for another day.

I watched Quadrophenia (1979) on DVD. And there is, of course, a Blu-ray edition. It’s also available to watch on Amazon Prime Video Download for a very reasonable £3.49, and, I suspect, other digital download channels.

You’ve just been reading a newsletter for both free and 'paid-for' subscribers. I hope you enjoyed it. Thank you to all those of you who have signed up so far.

There are two options on Luke Honey’s WEEKEND FLICKS. Cinema for Grown Ups: ‘Paid-for’ subscribers get an extra exclusive film recommendation every Friday morning, plus full access to the complete archive— which is currently at film no. 92, and should list over a hundred films by the end of the year. It costs £5 a month (or £50 a year)— a bargain, frankly, when you compare it to a few cups of coffee, a packet of semi-legal gaspers, or a pint of beer in the pub. ‘Free’ subscribers get access to the Sunday newsletter, plus the ‘free subscriber’ films in the archive. Either option is a good bet. And when I get my act together, I’m planning to add a spoken voiceover (mine!) for paid subscribers.

I will be back next Friday. Have absolutely no idea what I’m going to write about— but it will come. In the meantime, enjoy Quadrophenia and have a relaxing, cinematic Sunday.

.

I'm a huge Who fan Luke, have every album, Quadrophenia has a lot to say for itself, but Townshend was clever that way. You are spot on about the discrepancies in this movie (a bit of a head scratch) but I do love it (even in if some of the fashion choices of the wardrobe department were questionable -not strictly all mod and I've always been a little surprised about that one considering the mods lived by their fashion bible). Fantastic soundtrack and that beautiful moment of the reveal of the Bellboy (I can still hear Moon's camp cockney accent on this track). And so the Kids are Alright. Fantastic stuff !

Sting was never cooler!